God walks among the pots and pans.

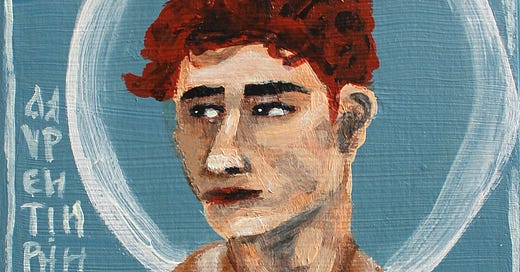

Advent Day 1: Brother Lawrence (1614-1691)

Welcome to Advent 2023!

I can think of no one better to welcome us into this rich season than Brother Lawrence. While there are saints credited with miracles, prophets who shout at the gates of power, and mystics famed for their ecstatic visions, Brother Lawrence belongs to a quieter, more relatable cohort of spiritual guides—those who’ve plumbed the depths of daily life and found God among the small details.

Lawrence was born in 1614, in the French province of Lorraine. Nowadays, Lorraine boasts Insta-worthy villages and pastoral farms. But back then it was ground zero in an epic conflict between European powers. By the time Lawrence was ten, the Thirty Years War had cut the population of his town in half; then a wave of bubonic plaque killed off many who’d survived that violence; on the heels of these twin cataclysms, a period of cooling now known as the Little Ice Age set in, leading to crop failure and widespread starvation.

These traumas touched everyone. But peasants like Lawrence suffered most. In 1632, desperate to escape hunger and poverty, Lawrence joined the army (as many still do to escape those things).

Over the next few years, Lawrence endured long marches through bitter cold and searing heat. He witnessed unspeakable violence. Many of his friends died from battle or disease. He received a serious leg wound that pained him for the rest of his life. He was captured by German troops and sentenced to death, only to be pardoned just before being hanged.

But amidst the horror, he also had a spiritual awakening which set him on the path to the rest of his life.

Lawrence’s awakening occurred, as it has for many mystics—and maybe for you, too—in nature. He was crossing a frozen field in the dead of winter when he saw a barren tree on a little hill. The quiet holiness of the scene stopped him in his tracks. In that moment, he was struck by the thought that what on the surface looked dead still contained life. He contemplated the force waiting under the earth, deep in the tree roots—a resurrection of greenness, leaves and fruit. In that moment he was given to realize that this endless pattern of life, death and resurrection was nothing less than the lovingkindness of God.

Standing in that snowy field, weakened by violence and starvation, he felt the stirring of a springtime God in his soul. A feeling of peace and love washed over him. He would spend the rest of his days not only seeking to live in fidelity to that peace and love, but to offer it to others.

After quitting the army, Lawrence made his way to Paris where he found work as a bottom-rung footman for a baron. He was ill-suited for the job. By his own account, he was rough and uneducated…a clumsy oaf who broke everything. His lack of elegance or social status precluded any hope of advancement. Many a night he ended up in tears, yearning for a deeper life. He had so much love in his heart and no idea what to do with it.

Finally, a kindly uncle took pity on him. Touched by the boy’s simple sweetness and heartfelt spirituality, he suggested Lawrence might find the life he longed for in a monastery. Unconvinced, Lawrence nevertheless decided to give it a go. In June 1640, he traded his footman’s frock coat for a friar’s habit and entered the Discalced Carmelite Monastery in Paris.

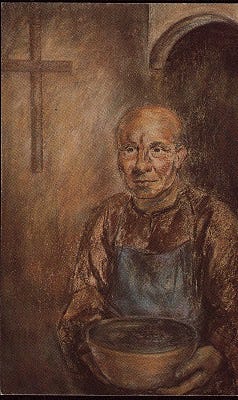

As a lay brother (though literate, he lacked the formal education required to be ordained) and low man on the monastic totem pole, Lawrence was assigned the least desirable job: the kitchen. There, among the pots and pans, peeling potatoes and chopping greens, Lawrence blossomed into an everyday saint.

With a spiritual simplicity that prefigured by more than two centuries the Little Way of Therese of Lisieux, Lawrence developed his revolutionary rule for living: do every task, no matter how small or mundane, with love and an awareness of God’s presence.

For Lawrence, God wasn’t only in the chapel or in the saying of prayers and performing liturgy. God was everywhere, in everything, all the time. While the more than one hundred monks he cooked for prayed and chanted upstairs, downstairs Lawrence made a prayer of stirring stew and cooking carrots. Counting off fistfuls of salt for a broth was his chant, sampling the loaves from the oven his eucharist.

For Lawrence, every act, no matter how small, was an opportunity for loving devotion to God, his fellow monks and all of creation.

It is not the greatness of the work which matters to God, but the love with which it is done. I flip my little omelet in the frying pan for the love of God.

This mindful presence did not come easy. By Lawrence’s own account, it took constant, faithful practice. This was especially true in his younger years when he struggled with many dark nights of the soul: anxiety, depression, war-induced PTSD, and spiritual drought. But the more he practiced—the more faithful he was to practice—the more this way of life and being became habitual. In his dedication to practicing through the ups and downs of life, he offers inspiration to anyone trying to live contemplatively in today’s world.

During his decades in the monastery, Lawrence was often left wanting by many of the formal aspects of religious devotion. Reciting creeds left him dry. His mind wandered during prayer. So much of what his fellow monks did seemed elaborate and unnecessary and, worse, to not have the desired effect. Despite lives of devotion, the monks seemed no more loving and no less anxious than the people on the outside of the monastic walls.

To Lawrence, it was a case of overcomplicating God.

Men invent means and methods of coming at God’s love. They learn rules and set up devices to remind them of that love. And it seems like a world of trouble to bring oneself into the consciousness of God’s presence…Overthinking ruins everything.

The main problem, as Lawrence saw it, was the artificial division of everything into sacred and profane. To him, everything was sacred, every moment an opportunity to practice love, service and gratitude.

[Living a sacred life] might be so simple. Is it not quicker and easier just to do our common business wholly for the love of God?

Though the other monks barely noted the humble brother in the kitchen, someone else did: a young priest named Joseph de Beaufort.

One day in 1666, while visiting the monastery on official business for the Cardinal of Paris, Joseph went to the kitchen to fetch a meal. There he found Lawrence presiding over the steaming pots and clanging pans. Welcomed into the space by Lawrence, he instantly felt the peace, love and joy which emanated from the brother.

[Lawrence’s] kind face, his understanding and warm ways, and his simple, modest manner immediately gained him the respect and goodwill of all who observed him.

Attracted to Lawrence’s simple kindness, and eager for more time with the monk, Joseph returned the next week, then the next. Soon—and for the next twenty-five years—the two met regularly for what, today, we would call spiritual direction.

After three decades in the kitchen, Lawrence’s old war injury began causing him constant pain. When standing for hours on his feet was no longer possible, the abbot placed him in charge of repairing the monks’ sandals, which allowed him to sit. During his long hours stringing leather and sewing soles, Lawrence and Joseph continued their sessions.

Joseph observed that despite Lawrence’s obvious spiritual depth, which far exceeded that of the other monks, Lawrence never lorded over others. Rather, like Jesus, Lawrence modeled humility and loving service.

The virtue of Brother Lawrence never made him harsh. His goodness made him gentle. He was a warm, welcoming person. He gave others confidence. When you met him, you felt you could tell him anything. You knew you’d found a friend…Once you got past his rough exterior, you discovered a unique wisdom, an openness of mind and a spaciousness…You could consult him on anything.

During his last years, Lawrence’s war wound troubled him greatly. But if his remarkable peace, love and joy flagged, no one left a record of it. Rather, he remained the same calm, collected Lawrence right up to the end.

After visiting him in his last days, Archbishop Fenelon of Paris wrote in a letter to a friend:

I went to see him when he was very sick yet very cheerful, and we had an excellent conversation about death…

Joseph de Beaufort held vigil at Lawrence’s bedside. In the account of those last days, he said that, once, when Lawrence lapsed into silence, a friar asked what he was doing. Lawrence replied,

I’m doing what I will do for all eternity. I am blessing God, I am praising God, I am worshipping God, and I am loving God with all my heart. Our whole profession, friends, is this. We worship God and love all, without worrying about anything else.

Lawrence died on February 13, 1691. He was seventy-seven. Like Therese of Lisieux centuries later, his anonymity in life was succeeded by fame in death. A year after his passing, Joseph de Beaufort compiled a volume of Lawrence’s wisdom from notes he’d taken during their conversations, and writings Lawrence had left in notebooks. Practicing The Presence Of God was an instant spiritual hit and has never been out of print.

It’s not difficult to see why. In this slim volume, a seeker finds Lawrence’s recipe for turning a whole life into a sacred prayer, as well as a path for those struggling to connect with an “upstairs” God. For those in that latter group, if Brother Lawrence were here today, he would counsel to not be discouraged but, rather, take the stairs down…down into the kitchen and into your heart where you’ll find the God of pots and pans waiting to welcome you with a warming stew of hope, love, joy and peace.

Advent Practice

Brother Lawrence saw the holy in every moment. As such, he gave his full presence (i.e. gratitude, curiosity and love) to what was right in front of him, as an offering to God.

Pick a task—something you do regularly and about which you don’t have strong feelings either for or against. Make it a situation where you normally zone out (e.g. doing dishes, driving to work, cooking, taking a walk, etc), put in ear buds, or are otherwise distracted. Now, offer this moment your sacred presence by asking yourself these questions:

What am I grateful for?

What would I notice if I were doing this for the first time?

What does this moment reveal about God?

If you find your mind has drifted, no big deal. Just bring it back by returning to these questions.

One example: taking a walk.

What am I grateful for? Breath moving in and out of my lungs, my leg muscles tightening and relaxing with each step, sun on my skin, the symphony of sounds, natural and human-made. (Personally, I find sensory details very centering as they help root me in the right now.)

What would I notice if I were taking this walk for the first time? What nature is up to. Are flowers blooming? Is the oak dropping leaves? What birds and insects are around? Who do I see as I’m walking around? Where is that person in the Toyota going?

What does this moment reveal about God? Body parts working in fellowship; the cycle of birth/death/resurrection in nature (including us); the grace of light and warmth; the mercy of comfortable sneakers.

Journal, pray or meditate on what you’re discovering in this practice.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

If you are in or near Austin, you’re most welcome to join us at our holiday gatherings. We are located at 205 East Monroe Street, one block east of South Congress in central Austin.

Dec 10, 11:15 am: LITC’s original holiday musical, Make Room In Your Heart.

Dec 21, 7 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the darkest night of the year.

Dec 23, 6 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve candlelight service, an annual LITC tradition.

Dec 24, 11:15 am: LITC’s regular Sunday service.

Dec 31, 11:15 am: A fun, casual service with cookies and coffee to welcome 2024.

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2023 edition of The Heart Moves Toward Light: Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Did you catch a typo? Do you have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets we might cover in the future? Leave feedback in comments section below or email Greg Durham at greg@lifeinthecityaustin.org.

It's been a while since I have thought about Brother Lawrence. Thank you for the reminder. I'm especially connecting to this line you wrote - "To Lawrence, it was a case of overcomplicating God." I don't want to be one who overcomplicates God or makes a divide between sacred/secular.

I have left the organized church and I am wandering in the wilderness. Thank you for these advent blessings. They nourish my soul more than you can imagine. Thank you.