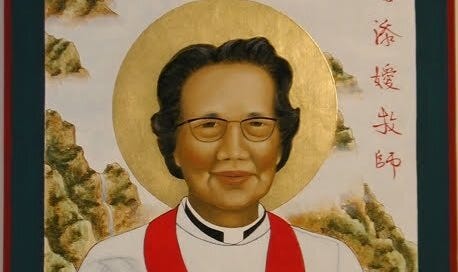

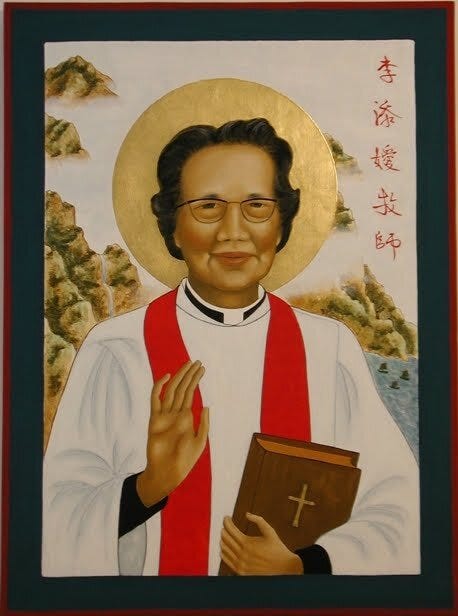

Advent Day 12: Florence Li Tim-Oi (1907-1992)

By 1970, Florence Li Tim-Oi had had enough. Once a groundbreaking figure as the first female Anglican priest—a woman who’d saved scores from starvation during the Second World War—since the 1950s she’d been branded a counter-revolutionary by the Maoists in China. Red Guard apparatchiks had forced her to cut up her vestments. They destroyed her home and subjected her to beatings and brainwashing. They stripped her of her church and title, and put her to hard labor in a “re-education” camp where they mockingly ordained her Queen of the Chickens. Now Florence couldn’t take anymore. She decided to end it all.

Florence’s journey from obscurity to historical figure to enemy of the state began in Hong Kong in May 1907. Born in a fishing village to progressive parents who valued daughters and sons equally, she was named Tim-Oi which means Most Beloved. Unlike nearly all girls of her time and place, she was given an education. While in school, she joined the local Anglican church (Hong Kong was a British colony from 1841-1997) and chose Florence as her confirmation name, in honor of her hero, Christian mystic, social reformer, and mother of modern nursing Florence Nightingale.

In 1931, at age twenty-four, Florence made a momentous decision that would launch her on the epic journey that became her life. At the ordination of an English deaconess, the priest put out a call seeking a Chinese girl who also wanted to serve the church. Florence answered that call.

In 1934, she began studying at Union Theological College in Canton. But by the time she finished her degree, the world had turned upside-down. In Europe, Hitler had annexed Austria and was preparing to invade the rest of the continent. In Asia, Japan had taken over most of China in a brutal occupation that would eventually kill 13 million. Like her namesake, Florence risked her life to administer aid to victims of the war, and several times narrowly missed becoming a casualty herself.

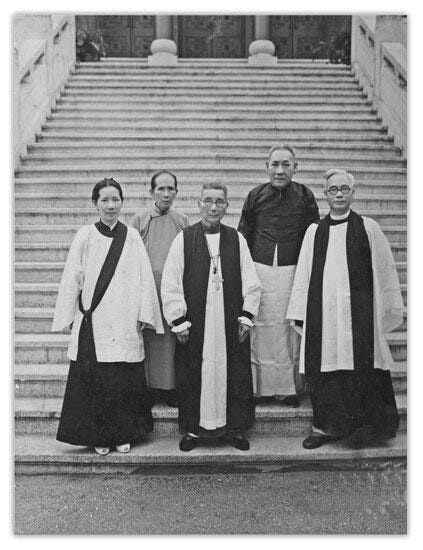

In 1941, now a deaconess, Florence was sent by Bishop Ronald Hall to neutral Macau and put in charge of the local Anglican congregation. The tiny territory was bursting at the seams with refugees who’d fled the Japanese. Conditions were horrifying. There was very little food. Starvation was rampant. Bodies piled up in the streets.

Florence threw herself into organizing relief efforts, to try and save as many as she could from starvation. She cut deals with food merchants who hoarded rice in order to keep prices artificially high. She set up a soup kitchen for the congregation and community, started a school for refugee children, and set up a system of medical care. She conducted countless funerals. Florence provided so much for so many, people began calling her, like her hero Florence Nightingale, the Lady of the Lamp, for the light of love and hope she shone into the darkness of war.

The pace was grinding. As Florence recalled:

I was working long hours, and I got to bed very late. Sometimes there would be midnight emergencies, when people would knock on the door and get me up. I would start work again at six o’clock. One day the doctor tested my chest. ‘If you carry on working like this,’ he said, ‘you will die very soon.’ But how could I stop? I didn’t sleep enough. I felt my heart pounding all the time, yet with so much to do I felt sure God would not let me die. I didn’t fear death, even though death was all around me.

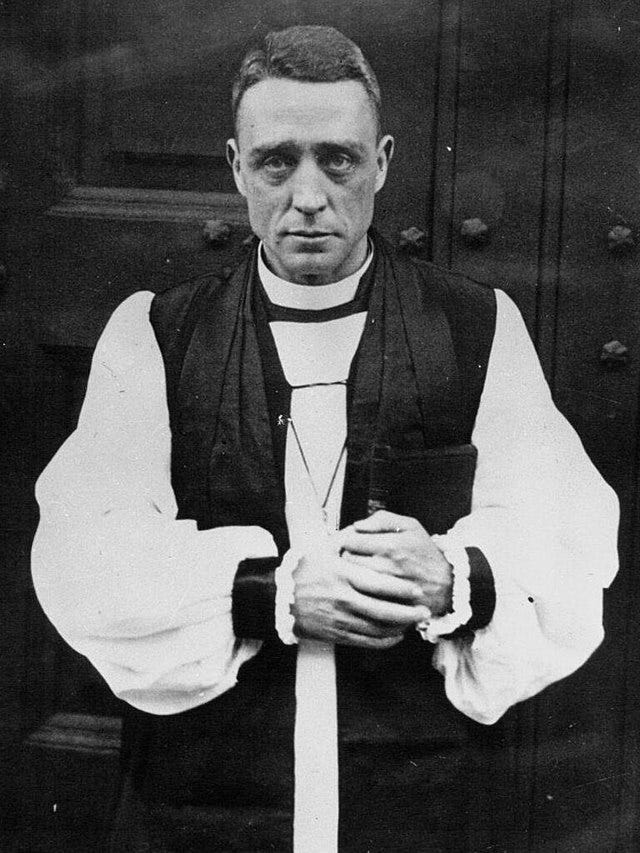

As the conflict raged with no end in sight, Bishop Hall found himself in a bind. The expanding Japanese occupation prevented priests from traveling between Free China and Macau. To do so risked death. So, he granted Florence a license to administer the eucharist in the absence of priests. But Bishop Hall had a thing about lay people presiding over communion: he just didn’t like it. Offering communion, he believed, was the exclusive privilege of the ordained. The problem? Florence was not ordained due to the Anglican communion’s strict No Girls Allowed policy on the priesthood. But war tends to bring out the practical side of people; soon Bishop Hall took an unprecedented and controversial step.

In January 1944, Hall asked Florence if she could try and reach him in the free city of Hsinxing. As a woman, Florence had a better shot at moving under the radar and avoiding arrest or conscription than a man, especially an Englishman. Florence agreed. On a winter night, she set off into enemy territory. She traveled by boat, bicycle, and for days by foot over a mountain range, avoiding bandits and Japanese soldiers.

After an arduous journey, she reached Hall on January 25th. In a rite attended by much of the town, he ordained her the first female priest in the Anglican communion. Later, defending his highly unorthodox move, he replied that he was only confirming what was already obvious: God had made Florence a priest.

The war ended in 1945. Soon, prejudices that had been sidelined for the sake of wartime practicality were revived. In 1946, the Archbishop of Canterbury decided that Florence’s ordination was a bridge too far, and he requested her resignation. Rather than fight the Purple Guard, as the Canterbury clique was known, Florence deferred…to a point. She resigned her priest’s license, but refused to renounce her Holy Orders. As Bishop Hall had said, it was God who made her a priest. No one could take the from her.

After the war, Florence administered a parish in Hepu, near the Vietnamese border. There, among her other duties, she started a large maternity home in order to try and reduce the murder of unwanted infant girls, a tragic but all-too-common practice in an era when parents preferred sons. It was a productive, and relatively quiet, few years for Florence. But peace wouldn’t last long.

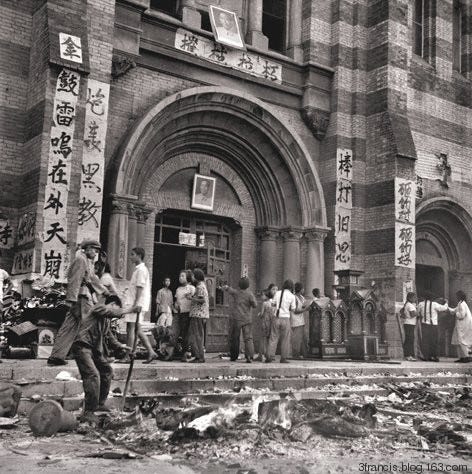

By the 1950s, the Maoists had completed their takeover of Chinese society. One of Maoism’s hallmarks was a harsh antagonism toward religion. In 1958, all religious institutions were shut down. Religious folks of every stripe—Christian, Buddhist, Taoist, etc—were targeted by the Red Guard for re-education. Florence was arrested and sent to a camp where she endured years of hard labor, torture and brainwashing. Though she managed to endure longer than many with whom she was imprisoned, by 1970 she’d lost the will to live.

The day she decided to kill herself, she climbed the mountain behind the chicken camp. She’d come here many times over the years to pray in secret. Now this is where she would end her life. But as she was contemplating suicide, she suddenly felt a presence all around her. And then, a gentle yet slightly indignant voice said, “Have you forgotten who you are? You are a priest!” Florence knew this was the Holy Spirit, reminding her who and whose she was. She said her prayers then descended the mountain, resolved to continue enduring.

Finally, in 1976, with the death of Mao Zedong, the brutal reign of the Red Guard came to an end. A few years later, Florence was given the chance to immigrate to Canada. She arrived in Toronto in 1983 and was promptly named an assistant priest by her local congregation.

Florence picked up just where she’d left off in 1946, bringing love and hope to people. Only a year later, she found herself in England where she was honored at Westminster Abbey on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of her ordination. At this point, no female priests had yet been ordained in the Church of England (though other branches of the Anglican communion were already ordaining women, starting with the Episcopal church in the US in 1974) and Archbishop Robert Runcie was publicly on the fence on the issue. But after meeting Florence, he acknowledged he’d been won over, saying, “Who am I to say whom God can and cannot call?”

As for Florence, she embodied in her final years that most core Christian value of forgiveness. According to Ted Scott, the Primate of Canada, who came to know her well:

She was never bitter, never harbored any resentment against those who caused her suffering. She had the resources to forgive all that had been done to her.

Florence, herself, took her newfound ecclesial acceptance, as well as her distinction as a first, in characteristic humble stride.

I know I’m not a diamond. A diamond experiences many cuts and polishings. I am just an earthen vessel with God’s treasure inside me.

Florence Li Tim-Oi died in 1992. In 2018, she was named a saint of the Episcopal Church in the United States.

Practice

Today’s practice is to honor a trailblazer who’s important to you. This can be a public figure from past or present, or someone you have known personally. Think expansively about what trailblazing is. For some, like Florence Li-Tim Oi, it is attached to vocational barrier breaking and takes on a public nature. But most trailblazers live their lives far from any spotlight: parents who sacrifice to give their children better lives, trans kids who live openly and honestly in the world, friends with hearts for serving the underserved…and a million other variations. We all know lots of trailblazers.

Today, pray for this person. Thank them for touching your life. If you have time, write them a note of gratitude in your journal. And if your trailblazer is still alive, consider going a step further and sending it to them in a card. I can almost guarantee it will be the best Christmas card they receive this season.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

Dec 21, 7 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the darkest night of the year.

Dec 23, 6 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve, an annual LITC tradition

Dec 24, 11:15 am: LITC’s regular Sunday service

Dec 31, 11:15 am: A fun, casual service with cookies and coffee to welcome 2024

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2023 edition of The Heart Moves Toward Light: Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Did you catch a typo? Do you have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets we might cover in the future? Leave feedback in comments section below or email Greg Durham at greg@lifeinthecityaustin.org.

Greg I'm so grateful to know this story! What a life!

I knew about Florence but now I know so much more! So inspiring!