Advent Day 13: Bill Wilson

Sharing is caring

In God's economy, nothing is wasted.

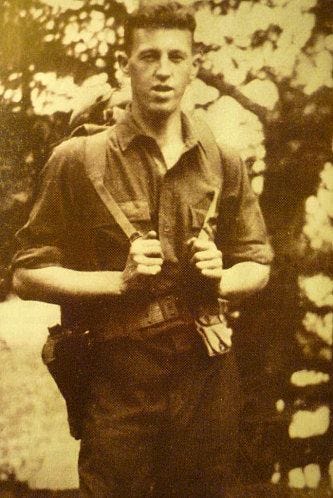

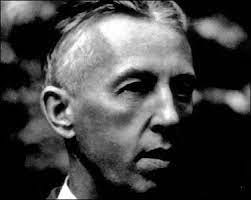

Advent Day 13: Bill Wilson (1895-1971)

In November 1934, Bill Wilson checked himself into NYC’s Towns Hospital to dry out. It was his fourth stay, and he arrived drunk, having barhopped his way over. His doctor got him settled in a room then started him on an elixir of barbiturates and belladonna, a regimen known as purge-and-puke.

For five days, Bill suffered the shakes, delirium and vomiting of withdrawal. Then the physical symptoms dissolved into a deep depression. He’d ruined his life. He had no job, no money. The only reason to keep living was his wife Lois. But she’d be a young widow if he couldn’t kick the bottle. So far he’d been a spectacular failure at that.

His mind cast back to the heady 1920s when he’d been a successful stock speculator, the trips he and Lois enjoyed, their roomy apartment. All that was gone. By Bill’s account,

Shame and failure had replaced success, and fear had banished security. Of romance there would be none, for presently I would die or go mad. This was the finish, the jumping-off place. The terrifying darkness had become complete.

Nowadays we call this hitting bottom. And Bill was down in the muck when his old friend and former drinking buddy Ebby Thacher came to the hospital to visit.

Ebby had recently gotten sober through his involvement in the Oxford Group, a popular Christian movement started by a Lutheran pastor who saw that institutional religion often failed to transform people’s lives on a deep, spiritual level. Oxford’s program for healthy minds, bodies and souls, steeped in the teachings of Jesus, had attracted countless adherents across the US and Europe, including Joe Dimaggio, Mae West, Harry Truman and Henry Ford.

Ebby shared his own story and suggested Bill try Oxford. Bill wasn’t having it. He didn’t go in for God. He was a commonsense New Englander—a real pull yourself up by the bootstraps type. He saw his alcoholism as a technical problem with a technical solution (i.e. willpower, medicines), not a spiritual problem with a spiritual solution.

No cure that fails to engage the spirit can make us well. Viktor Frankl

Ebby understood that many people had grown up on an image of God as a fire-and-brimstone big daddy in the sky. This image not only failed to resonate, it alienated. And it seemed in direct opposition to the gospel of the compassionate healer Jesus, and the loving father-God Jesus called Abba. This is where Bill stood. But Ebby knew the deep spiritual life wasn’t about believing in God, it was about knowing God. So, he suggested Bill seek God on his own and see what he find. In essence, Ebby was prescribing the mystical quest.

Later, Bill wrote,

(That) hit me hard. It melted the icy intellectual mountain in whose shadow I had lived and shivered many years.

That night after Ebby left, Bill issued a challenge: If there be a God, let him show himself!

The effect was instant, electric. Suddenly my room blazed with an indescribably white light. I was seized with an ecstasy beyond description. I have no words for this. Every joy I had known was pale by comparison. The light, the ecstasy. I was conscious of nothing else for a time. Then, seen in the mind’s eye, there was a mountain. I stood upon its summit where a great wind blew. A wind, not of air, but of spirit. In great, clean strength it blew right through me. Then came the blazing thought, “You are a free man.” I know not at all how long I remained in this state, but finally the light and the ecstasy subsided. I again saw the wall of my room. As I became more quiet a great peace stole over me, and this was accompanied by a sensation difficult to describe. I became acutely conscious of a presence which seemed like a veritable sea of living spirit. I lay on the shores of a new world. “This,” I thought, “must be the great reality. The God of the preachers.”

This was Bill’s road-to-Damascus moment—knocked off his proverbial horse, blinded by the light, to rise spiritually changed. Like the Apostle Paul, Bill underwent an immediate and profound shift in consciousness. He would spend the rest of his life—again like Paul—spreading the good news that through self-surrender and disciplined spiritual practice we may heal what hurts us.

Bill Wilson was born in 1895 in Dorset, Vermont. When he was young, his parents abandoned him. His father never returned from a business trip to Canada, then his mother went off to study medicine, leaving Bill to be raised by his grandparents. It was a primal wound that punched a hole in his soul. Though peers remembered him as handsome, smart and charismatic, Bill felt perpetually awkward, anxious and needy.

In 1916, Bill was called up to military service in advance of America’s entry into World War I. At a party during basic training, he was handed his first drink, a so-called Bronx cocktail: gin, sweet vermouth and orange juice. The reaction was swift, and Bill’s description of it will resonate with anyone who’s ever felt liquor’s lubricating effects:

I took (the drink), and another one, and then, lo, the miracle! That strange barrier that had existed between me and all men and women…seemed to instantly go down. I felt that I belonged where I was, I belonged to life, I belonged to the universe, I was a part of things at last. Oh, the magic of those first three or four drinks! I became the life of the party. I actually could please the guests. I could talk freely, volubly. I could talk well.

His drinking career spanned seventeen years—through war, marriage to Lois, a lucrative Wall Street career. The last of those helped him sustain the illusion he had his act together. He was, for a long time, a functioning drunk. As long as he was able to work and make money, what was the problem? There was no problem!

Then came the crash of 1929. Overnight, the Wilsons went from living in a fancy apartment to crashing on Lois’s parents’ couch. It was the start of Bill’s downward spiral. The next few years saw an ever-worsening series of alcoholic binges, squandered opportunities and self-sabotage until the night in his hospital room when he saw the light.

Bill’s post-hospital life took a swift and positive turn. He was healthier than he’d been in years. His marriage was refreshed. He even reestablished old Wall Street connections which brought him job prospects. With his pal Ebby he began attending Oxford Group meetings. At Oxford, people were taught that the source of all the world’s problems came from profound disconnection from one another, one’s self and God. Heal the disconnection, you heal yourself and the world.

The Oxford Group operated on what it called Four Standards: honesty, purity, unselfishness and love, which were a summary teaching of Jesus’s Sermon On The Mount. To cultivate those values, Oxford laid down four spiritual practices:

Sharing our sins and temptations with others.

Restitution to all whom we have wronged, directly or indirectly.

Surrender our life past, present and future, to God's keeping and direction.

Listening for God's guidance, and carrying it out.

Bill Wilson embraced these practices with the zeal of the converted, and in them are the seeds of the 12-step program he would later develop. He was especially passionate on the third point—the one he’d so resisted when Ebby talked about it at the hospital—that lasting sobriety could only come when the drinker had undergone a spiritual rebirth.

(It should be noted here that famed Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung was critical to the shift from viewing alcoholism as a technical illness due to a failure of will, to a spiritual illness whose cure lay in spiritual rebirth. In the early 1930s, Jung treated Rowland Hazard, an American businessman who brought this idea about spiritual rebirth back to the Oxford Group. He gave it to Ebby Thacher who gave it to Bill Wilson who gave it to the world.)

Bill’s special concern at Oxford was the alcoholics. Soon, he had launched an offshoot meeting of men trying to get sober. At these meetings he would share how the Oxford principles and rules had helped him kick the bottle. The men would listen in silence then go back to their lives to practice on their own. It didn’t take Bill long to notice that, though Oxford had worked for him, most alcoholics he met there couldn’t sustain sobriety.

In spring 1935, a fateful meeting took place when Bill temporarily moved to Akron Ohio to scout a business deal with the National Rubber Machinery Company. He’d been sober five months. When the deal fell through, he found himself tempted by the hotel bar. Desperate for a lifeline, he scanned the phone directory for the local Oxford Group.

That evening, he landed at the home of local doctor Bob Smith. Like Bill, Bob was a surly, skeptical Vermonter. He was also an active alcoholic. When Bill started talking about his sobriety, Bob figured Bill was about to start preaching at him. He said he didn’t want to hear it. Bill then told Bob he’d got it wrong. It was he, Bill, who’d come seeking help. He was feeling tempted to drink, and he needed to talk to the only person he thought could help him through: a fellow alcoholic.

That night was a breakthrough that changed the way alcoholism was treated. Bill had the epiphany that all the anti-drinking programs and practices in the worlds were useless if alcoholics didn’t first have fellowship. Addicts (and every other human being) needed to know they weren’t alone, to be joined in what Bill called a kinship of suffering—to know that who they were and what they’d been through could add up to something and be of service to others—as the Apostle Paul said, “…so that we may be able to console those who are in any affliction with the consolation with which we ourselves are consoled by God.”

Bill said simply of that first night with Bob,

I knew that I needed this alcoholic as much as he needed me. This was it!

Through the summer of 1935, Bill and Bob—who took his last drink that June—spent long hours together sharing their stories and struggles. Other alcoholics who’d been working the Oxford program soon joined them. It didn’t take Bill and Bob long to notice that this mutual aid society was more effective in getting people sober than medical treatments, willpower, or Oxford’s principles on their own had ever been. The two men were so excited, they hatched plans to grow their little meeting into a nationwide network. Though it didn’t yet have the name, Alcoholics Anonymous had been born.

Almost without exception alcoholics are tortured by loneliness. Bill Wilson

Word of the Akron group’s success spread quickly. Soon, new meetings were springing up throughout Ohio. Back in New York, Bill dove into systematizing what had happened in Akron so that it could be duplicated. These were lean times. Not wanting his nascent organization to be corrupted by money or corporate influence, Bill refused any grants that came with strings attached, and all offers to develop the program at hospitals and for-profit institutions. This principled stand has served AA well, but it meant that, in the early days, its founder and his wife had to continue crashing on her parents’ couch, eating beans out of cans and subsisting off Lois’s income from her job as a saleswoman at Macy’s.

Bill decided the best way to spread the gospel of AA was by publishing a book. With the help of a number of people who’d gotten sober through his program, including writers from the New York Daily News and New Yorker magazine, Bill created a draft. In April 1939, Alcoholics Anonymous—commonly referred to as The Big Book—was published.

The core of AA, as laid out in the book, is the 12 steps. These steps are a synthesis of all Bill had learned through the years about what it took to get and stay sober. Many evolved from his time in the Oxford Group: honest self-examination, making amends, humility, practice of prayer and meditation to God as we understood him (While Bill was Christian, he was adamant AA not be affiliated with any religion, and that seekers follow the mystical path Ebby had prescribed to him, to seek God on their own; today you will find AA groups meeting in Jewish synagogues, Muslim mosques, Buddhist and Hindu temples, Christian churches, and secular spaces). But steps 1 and 12 were his.

Step One: We admitted we were powerless over alcohol—that our lives had become unmanageable.

Admitting powerlessness—that we don’t have the control over our lives we think, or wish, we have; that we can’t fix everything, or anything, alone; that we can’t grow in compassion if we’re spending our lives in the muck of self-delusion; that we are at the mercy of a Love we can’t control—only comes for most addicts at rock bottom. It’s the point where we finally cry uncle. But it’s in admitting the powerlessness that we find the strength.

This is one of life’s great paradoxes, put best by Paul in his letter to the Corinthians: when I am weak, I am strong. In the defeat something magical happens. Paul got this. Bill Wilson got it. But to this day, our human cultures and institutions and egos fight this spiritual truth tooth and nail.

Step Twelve: Having had a spiritual awakening as the result of these steps, we tried to carry this message to alcoholics and to practice these principles in all our affairs.

The key phrase here is having had a spiritual awakening. If undertaken sincerely, if reflected on, practiced, and returned to again and again, the eleven preceding steps will necessarily lead to spiritual waking, to getting closer to a light that never fails. And then it is one’s duty to model what spiritual awakening looks like so that others may be led to their own awakenings.

Sales of Alcoholics Anonymous were slow for the first couple years. Then, in March 1941, The Saturday Evening Post—the most popular periodical in America—printed an article about it. Within two weeks, more than six thousand inquiries had poured into the Post’s office, with people wondering how they could start an AA group in their area. Almost overnight, AA went from being localized in Ohio and New York to setting up outposts across the continent.

Bill Wilson remained at the head of AA until 1955. During those years he continued to turn down opportunities he felt might personally benefit him, but that would compromise the group or its principles. Among countless accolades, he refused lucrative job offers, an honorary doctorate from Yale, a listing in Who’s Who In America, and—in keeping with the principle of anonymity—his face on the cover of Time Magazine.

In the years after retiring from his position at the head of AA, he continued to pursue his interests in spirituality, psychology and addiction recovery. He and Lois—who, in 1951, created Al-Anon, the support group for family members of addicts—traveled extensively around the country, appearing at AA conferences, and meeting scientists and researchers in the new field of addiction research. He maintained friendships with notable thinkers of the era, including Carl Jung and Aldous Huxley who called him the greatest social architect of our century. Wherever he went, he was lauded for having saved so many lives.

Bill brushed off the accolades. As Susan Cheever writes in My Name Is Bill:

He tried to discourage the idea that he was a leader, or any kind of model for human behavior. He had a lot of help, and he always acknowledged that. He fought the idea of himself as a hero; he knew better. The brilliance of his guidelines for the operation of A.A., the Twelve Traditions, reflects his understanding of his humanness and his desire to be judged as a man, not as a leader. Bill Wilson never held himself up as a model; he only hoped to help other people by sharing his own experience, strength, and hope.

Bill Wilson died in 1971. In 1999, Time named him one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century. Though addiction treatment continues to evolve, his revolutionary spiritual approach—which has since been applied to every kind of addiction—remains the gold standard.

Advent Practice

Spiritual rebirth is core to the sobriety experience. On the surface, this will look a bit different for everyone, depending on one’s temperament, traditions and personal history. But the bedrock of true spiritual transformation is the same: in the seemingly counter-intuitive words of Jesus: to save your life, you must first lose your life. All seekers, whether they’re in 12-step programs or not, whether they’re religious or not, are searching for a return to original wholeness of mind, body and spirit…a lovingkindness that, day by day, roots deeper in the soul even as it ripples out to the rest of the world.

For practice today, read and meditate on this poem from Sufi mystic and poet Rumi.

Lose yourself,

Lose yourself in this love.

When you lose yourself in this love,

you will find everything.

Lose yourself,

Lose yourself.

Do not fear this loss,

For you will rise from the earth

and embrace the endless heavens.

Lose yourself,

Lose yourself.

Escape from this earthly form,

For this body is a chain

and you are its prisoner.

Smash through the prison wall

and walk outside with the kings and princes.

Lose yourself,

Lose yourself at the foot of the glorious King.

When you lose yourself before the King

you will become the King.

Lose yourself,

Lose yourself.

Escape from the black cloud

that surrounds you.

Then you will see your own light

as radiant as the full moon.

Now enter that silence.

This is the surest way

to lose yourself. . . .

What has your life been about, anyway? —

Nothing but a struggle to be someone,

Nothing but a running from your own silence.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

Dec 21, 7 pm: Blue Christmas, a contemplative service for the darkest night of the year.

Dec 23, 6 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve candlelight service, an annual LITC tradition.

Dec 24, 11:15 am: LITC’s regular Sunday service.

Dec 31, 11:15 am: A fun, casual service with cookies and coffee to welcome 2024.

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2023 edition of The Heart Moves Toward Light: Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Did you catch a typo? Do you have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets we might cover in the future? Leave feedback in comments section below or email Greg Durham at greg@lifeinthecityaustin.org.

What a fascinating character! My wife and several others I know really benefit from Al-Anon. I’m grateful for Bill and Lois and their dedication to each other and those who have suffered as they suffered. Alcoholism is one of those “sins” that really shows the negative effect these destructive tendencies that sin can have on oneself and those around them. It reminds me of a definition of sin I once heard that I think fits perfectly with today’s story and those two Sundays of Advent: sin is a culpable disturbance of shalom.

This also led me down an enjoyable rabbit hole of research into the Oxford House movement and its impact on the Anglican and Episcopal church as well as the campus ministry I did for 19 years with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship which heavily emphasized “quiet time” with God.