Advent Day 14: Josephine Bakhita (1869-1947)

The girl was nine years old when she was stolen. It was a sunny and mild morning in the village of Olgossa in the Darfur region of South Sudan where she lived among the Daju people. After breakfast, she and a friend went for a walk. They’d passed through the village fields, just beyond sight of the nearest house, when two armed men stepped from the woods. The men gave the girls a once-over, conferred briefly in Arabic, then told the friend to run along. When the friend was out of sight, one of the men pressed his dagger to the girl’s side and vowed to kill her if she screamed.

The men—slave traders— marched her through the woods, deep into the countryside, farther than she’d ever been from her village. Shoeless, she was force-marched over rocks and through brambles until her legs and feet bled. She sobbed all day and through the night for her parents. Finally, at dawn, they arrived at the home of one of the traders. There, she was locked in a dark, bare room where the only light came from a hole in the roof.

Days turned into weeks. The girl spent long hours staring up at the sky through the hole in the roof. She had always felt a loving presence around her, though she’d never shared this with anyone. Despite her dire circumstances, she felt it still, and she began to wonder for the first time what that presence was—who it was.

Seeing the sun, the moon, and the stars, I said to myself: Who could be the master of these beautiful things? And I felt a great desire to see, to know, and to pay honor.

After being locked up for a month, her kidnappers sold her to a trader who placed her in chains alongside others who’d been captured in the bush, and gave her a new name—Bakhita, which means lucky one in Arabic. Eventually, Bakhita would forget her birth name. Like that of so many enslaved through history, it was lost in a fog of trauma, terror and displacement.

Later, Bakhita recounted that, in those first months, as she was carted from city to city in chains, she felt that Presence near to her, sustaining her. Then, one night, she had a vision that would shape and inform the rest of her life.

She and a fellow slave managed to loosen their chains. When the trader went off to conduct some business, they bolted. The first night on the run they became lost in the woods. Frightened as the night closed in on them, Bakhita suddenly had a vision of an angel. This figure beckoned her to follow. Not revealing to her friend what she was seeing, Bakhita followed and soon they were out of the woods. Bakhita came to believe this was her guardian angel who’d appeared to her. Though she never had another vision like this, the strength and courage she took from the experience lasted her entire life.

But her freedom was short-lived. Soon, she and the other girl were placed in chains by a farmer from whom they sought food. He then sold them back to slave traders.

Eventually, a wealthy Arab family living in the province of Kordofan bought Bakhita. A year later, they sold her to a Turkish general stationed in Khartoum who gifted her to his wife. It was the worst time of Bakhita’s life.

During the years I stayed in that house, I do not recall a day that passed without some wound or other. When a wound from the whip began to heal, other blows would pour down on me.

In the general’s home, she endured the most traumatic experience of her enslavement: being tattooed with one hundred and eight slices of a razor—sixty on her stomach, forty-eight on her right arm—branding her the property of the general’s wife.

In 1883, the Turks fled the city in advance of an invasion by Islamic revolutionaries. The general sold Bakhita to Callisto Legani, the Italian consul in Sudan. Life with the Legani was a relative reprieve compared to what had come before. According to Josephine:

This time I was truly lucky, because the new master was very good and very fond of me. My job was to help the chambermaid with housework. I did not get scolded, punished, or beaten; it did not seem true that one could enjoy such peace and tranquility.

It wasn’t freedom; but for someone whose heart dared not hope for such, it was the best she could imagine.

In 1885, Legani was called back to Italy. Fearful of being sold to a cruel master, Bakhita made a bold move: she asked Legani to take her with him.

Legani said no. The trip was too dangerous, passing through territory controlled by warlords, bandits and slavers. By going, Bakhita risked death or being captured and tossed into even worse circumstances than she’d known before. Bakhita said she was willing to take the chance. Impressed by her bravery, Legani agreed.

The 1500 mile trip took two months on a circuitous route of walking, boats and camel caravans. Finally, in April 1885 they arrived in Venice. There, Legani gave Bakhita to the Michielis, a family of wealthy hoteliers.

While Augusto Michieli was the de facto head of the family, it was his mother, Lady Turina, a Russian atheist, who lorded over the home. When Turina’s daughter-in-law had a daughter named Alice, she put Bhakita in charge of the girl. According to Bkahita, the woman gave her freedom to raise Alice as she saw fit. Turina had only one strict rule: neither Bhakita nor the girl could be exposed to religion of any sort.

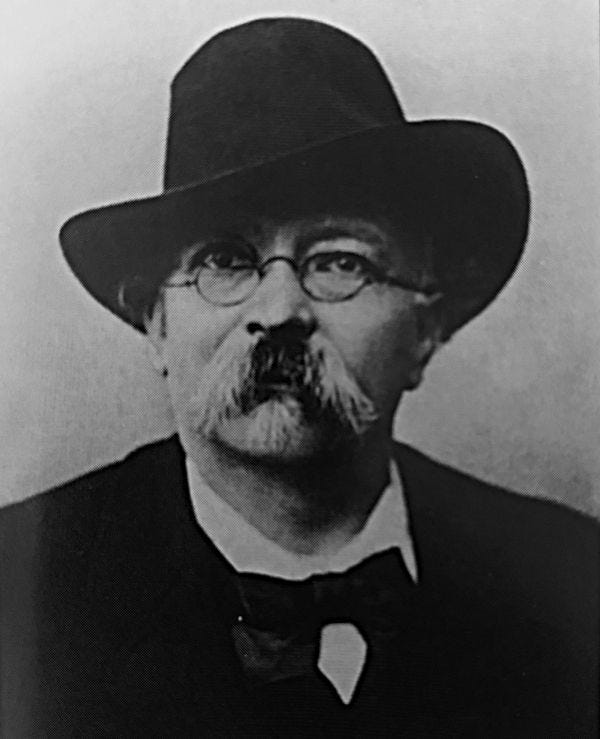

Enter the Michielis’ estate manager: the devout, extravagantly mustachioed Illuminato Checchini. When Turina was occupied with other matters, Illuminato began to whisper to Bakhita about the God he knew…the Master of masters, a God of love before whom all distinctions dissolved, and there was no longer free or slave, male or female, rich or poor, but all were equal in love. A God who loved her, a girl stolen from her homeland, the lowest of the low, as much as he loved any queen.

This was the Presence Bakhita had sensed all her life, who’d sustained her through hell and never left her. This God had incarnated in Jesus, a poor carpenter who ministered to the downtrodden, fed the hungry and healed the heartsick, and who was flogged as she’d been flogged. This Jesus had been crucified, but then overcame physical death as she’d overcome spiritual and cultural death.

Now Bakhita understood the significance of all the crosses she’d seen since coming to Italy. She felt a powerful connection to the symbol. When Illuminato secretly gave her one, she treasured it and hid it away where Lady Turina wouldn’t find it.

I was moved by a mysterious power…I had never been attached to anything before. I remember that I looked at the cross in secret and felt something that I could not explain…This was the God I’d felt since childhood.

Though Bakhita’s mystical awakening had begun in childhood, it now took on full expression and was given a language.

Illuminato was also key to the final step into the rest of Bakhita’s life. When the Michieli’s went to Africa for a year, he somehow convinced the rabidly anti-religious Turina to place Bakhita and the young Mimmina Michieli in the care of the Canossian Sisters at the Institute of Catechumens in Venice. It was a decision Turina would come to regret.

It was a fateful year. Bakhita was now twenty years old. She’d been someone’s property for more than half her life. No one ever asked her if she wanted anything different, or anything at all. But now Sister Maria Fabbretti, who’d been tasked with looking after Bakhita, asked her if she’d like to be a Christian. Bakhita replied she would. But it would involve fighting for her freedom.

After nine months, Lady Turina returned. Her plan: to fetch Bakhita and Alice and take them back to Africa where the Michielis had opened a hotel. Bakhita refused to go. First, she did not want to return to the Sudan where she risked being sold again. More important, however, was this: it was impossible, she said, to serve two masters. Between the Michielis and Jesus, Bakhita had to pick. And she picked the humble carpenter from Galilee over the wealthy Italian hoteliers.

Drama ensued. Turina begged and pleaded for Bakhita to return to her. The dispute eventually involved lawyers, Venice’s Cardinal Sarto (later Pope Pius X), the convent Superior, and King Umberto I. In the end, Bakhita got what she wanted. On November 29, 1889, in a scene reminiscent of Dorothy finding out in Oz that she’d always had within her the power to go home, the king’s attorney general informed Bakhita that since there was no slavery in Italy, she was already free, and had been since she stepped foot on Italian soil. And she was free to do as she pleased.

Turina left in a huff. A month later, Bakhita was baptized and confirmed. For her confirmation name she chose Josephine. It was the name that meant the most to her, she said, because it was the one she picked for herself.

In the 21st century it is difficult to imagine a religious figure other than the Dalai Lama or the Pope achieving celebrity status. But this is exactly what happened with Josephine. After moving to the Canossian convent in the city of Schio, she became noted for her kindness, devotion to others and her personal charisma, so much so that her Superior often sent her on tours around Italy. On the road, she drew large crowds, especially following the publication of a book about her life.

Once, during one of these tours, a young man asked what she would say to the Arab slavers who’d stolen her, if she met them today. Josephine replied from the high mystical viewpoint that could see her entire life and understood that if one thing had changed—even the most horrible things, of which there’d been many—she would not be who she was and where she was:

If I were to meet those who kidnapped me, and even those who tortured me, I would kneel and kiss their hands. For, if these things had not happened, I would not have been a Christian today.

Though she was a celebrity out on the road, it was in her convent, living the simple life, where she was happiest and felt most at home. Now free to go where she wanted, where she wanted to be was in a place she could call her own in a community she could call her own where she was loved and respected and free to devote herself to serving because she was called to it, not because she was someone’s property, doing it for their pleasure.

She became Schio’s most famous resident and was considered by the citizenry to be a living patron saint. During World War II, her presence there convinced many that they were protected. And, in fact, though Schio was bombed, no one lost their lives there due to that bombing. Many credited the saintly Josephine for this.

After the war, Josephine’s health began to fail due to heart disease and injuries sustained in a fall which often confined her to a wheelchair. By the beginning of 1947, she could no longer leave her bed. In her last few weeks, many came to visit. Josephine told each one she’d pray for them and would see them one day in Paradise. Then, on the evening of February 8, 1947, seeming to slip back into her memories, she asked one of her fellow nuns to loosen the chains around her feet. Not long after, she appeared to be having a vision. “Our Lady, our Lady,” she exclaimed. They were her last words.

As word of her death got out, crowds converged on the convent. Author Roberto Zanini recounted:

The crowds that came streaming to her room of repose were endless. Hundreds of children stood before her corpse, showing no signs of fear but, instead, looking upon her with awe and amazement, caressing her and laying their heads gently against the hands of the deceased nun, whose body remained incredibly soft and warm.

In Italy, Josephine Bakhita remains a beloved figure. She is now considered one of the country’s patron saints, as well as the patron saint of those who’ve survived human trafficking. In 2002, in the process of canonizing her, Pope John Paul II called her a universal sister, a woman whose bound body held an unbounded spirituality; a woman whose journey from slavery to sainthood holds inspiration and value for everyone, in all times and places.

Practice

Forgiveness is at the heart of Jesus’s teaching. It was also one of Josephine Bakhita’s core values.

For today’s practice, ask yourself, For what would I like to forgive? By whom would I like to be forgiven? To whom would I like to be reconciled? Meditate, journal or pray your answers.

Bonus practice

Read this passage from the Gospel of Matthew and reflect on it through Lectio Divina. For a primer or refresher on Lectio Divina, view this video from Father James Martin.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

Dec 21, 7 pm: Blue Christmas contemplative service for the darkest night of the year.

Dec 23, 6 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve candlelight service, an annual LITC tradition.

Dec 24, 11:15 am: LITC’s regular Sunday service.

Dec 31, 11:15 am: A fun, casual service with cookies and coffee to welcome 2024.

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2023 edition of The Heart Moves Toward Light: Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Did you catch a typo? Do you have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets we might cover in the future? Leave feedback in comments section below or email Greg Durham at greg@lifeinthecityaustin.org.

I love Josephine Bakhita’s story! What a grace for her to see God’s hand and presence even through the extremely hard trials of her life. One typo I found: “Not long after, she appeared to be having. “Our Lady, our Lady,” she exclaimed. They were her last words.”

I love her wisdom in thanking her captors and torturers. Since we can’t change the past, this perspective is the only path to peace. I love how this disposition is foreshadowed in her embracing the symbol of the Cross.