Advent Day 16: Carl Jung

Our task is not goodness, it’s wholeness.

Our task is not goodness, it’s wholeness.

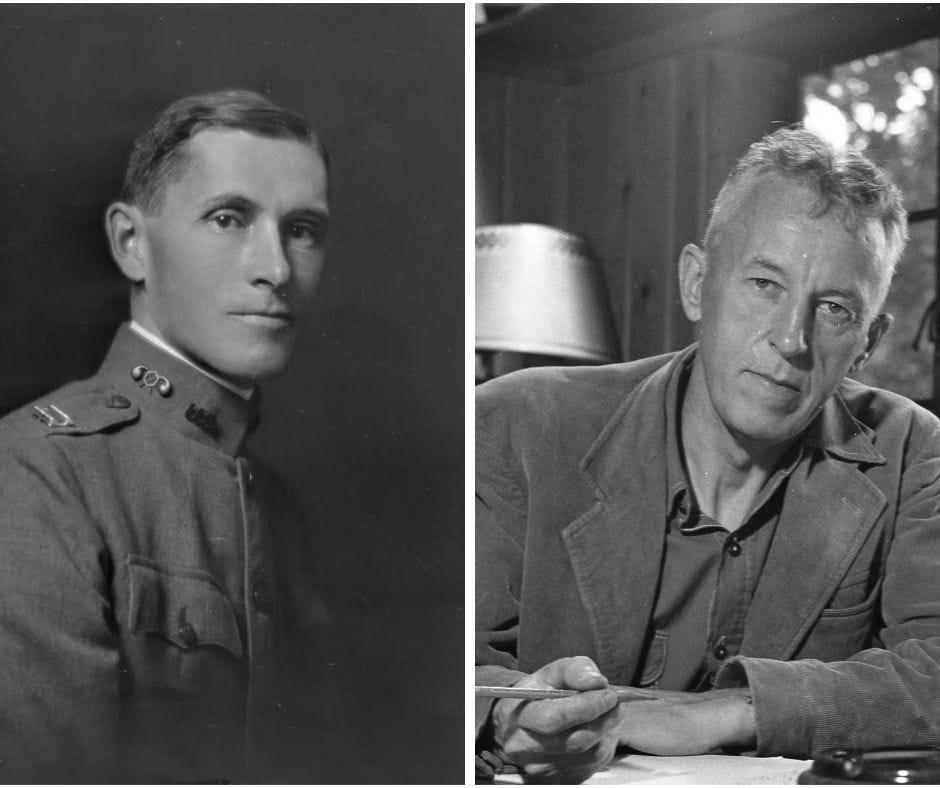

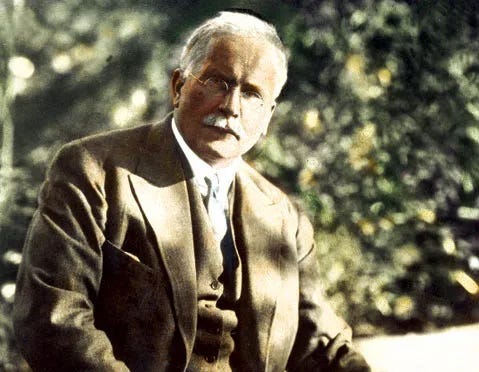

Advent Day 16: Carl Jung (1875-1961)

The letter arrived out of the blue from America. The sender was a man named Bill Wilson. The recipient was Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, one of the most significant figures of the 20th century, now an old man. Letter in-hand, Carl shuffled to his office and settled in a chair next to the window where he could see the snow falling. With fingers frigid from poor circulation, he opened the envelope and began to read.

January 23, 1961

My dear Dr. Jung,

This letter of great appreciation is long overdue. May I first introduce myself as Bill W., a co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous. Though you have surely heard of us, I doubt you are aware that a conversation you once had with one of your patients, a Mr. Rowland H., played a critical role in the founding of our Fellowship.

Our remembrance is as follows: Having exhausted other means of recovery from his alcoholism, Roland became your patient for a year in 1931, and left you with a feeling of much confidence. To his great consternation, he soon relapsed. He again returned to your care. Then followed the conversation between you that was to become the first link in the chain of events that led to the founding of Alcoholics Anonymous.

First of all, you frankly told him of his hopelessness so far as any further medical or psychiatric treatment might be concerned. Coming from you, one he so trusted and admired, the impact was immense. When he then asked if there was any other hope, you told him there might be: a spiritual or religious experience--in short, a genuine conversion. You recommended that he place himself in a religious atmosphere and hope for the best.

Shortly thereafter, Mr. H. joined the Oxford Group, a movement with a large emphasis upon the principles of self-survey, confession, restitution, and the giving of oneself in service to others. They strongly stressed meditation and prayer. In these surroundings, Rowland H. found a conversion experience that released him from his compulsion to drink.Bill goes on to recount how a newly-sober Rowland H. spread Jung’s belief to other addicts—that their problem was, at root, not medical or scientific but spiritual, and demanded a spiritual cure. With this revolutionary paradigm-shift, many who for years had tried and failed to quit drinking were now able to.

One was Bill’s friend Ebby. Ebby then helped Bill who was, at the time, close to drinking himself to death. Bill goes on in his letter to describe his own conversion experience (which you can read about in yesterday’s entry) and the aftermath:

My release from alcohol was immediate. I was a free man. Shortly following, my friend brought me a copy of William James' Varieties of Religious Experience. This book gave me the realization that most conversion experiences, whatever their variety, have a common denominator of ego collapse at depth.

In the wake of my spiritual experience there came a vision of a society of alcoholics, each transmitting their experience to the next, chain-style. This concept proved to be the foundation of Alcoholics Anonymous.

So to you, we of AA owe this tremendous benefaction. As you see, this astonishing chain of events actually started long ago in your consulting room, and is directly founded upon your own humility and deep perception. Because of your conviction that man is something more than intellect, emotion, and two dollars worth of chemicals, you have especially endeared yourself to us. Please be certain that your place in the affection, and in the history of the Fellowship, is like no other.

Gratefully yours,

William G.W.Jung sat unmoving for a moment. Never had he imagined that his work with a patient so long in the past had sparked a movement that revolutionized addiction treatment and saved millions. It was nearly unbelievable. He read the letter a second time to be sure he had not misunderstood. Then he pushed himself up from his chair, went to his desk and began to type a reply.

Carl Jung was born in Switzerland, in 1875, to a pastor father and homemaker mother. Both parents had significant personal struggles. His father lived with a constant crisis of faith brought on by a strict Swiss-Protestantism he dutifully adhered to, but which he found spiritually dead. His mother was erratic—warm one moment, distant and depressed the next—and hospitalized for long periods. Carl had complicated feelings about both. Yet planted in his childhood were seeds that bloomed in his later life: a probing exploration of spirituality, and a fascination with the unconscious.

Like many children, Carl was spiritually attuned. Beneath the family disorder he sensed a “deeper, secret order.” Something stirred in his soul—a sense of connection to a sustaining Presence that lived far below the surface of everyday life.

These mystical intuitions led him in his teens to consider becoming a minister. But when he looked at his father’s life, and the Swiss church’s intellectual approach to faith, he found, “I could not make myself believe that the salvation of man had anything to do with the routine of the Church”. He turned then to medicine. But late-19th century medicine had been swept up in a cold scientism that regarded humans as little more than—as Bill Wilson later said in his letter to Jung—two dollars worth of chemicals.

There was, however, a new field of study, one which took seriously both the outer and inner life: psychiatry. Carl looked into it and was immediately hooked. After completing his studies at the University of Basel, he took a post at a psychiatric hospital in Zurich. There he established himself as the brightest young star in the new field. At the tender age of 29, he was named a permanent senior doctor and lecturer (i.e. tenure).

In 1907, Carl had one of the most fateful meetings of his life when he was introduced to Sigmund Freud. Freud, the father of psychoanalysis, was then in mid-career and seeking acolytes who would help him spread his ideas. The bond between he and Carl was instant and electric. According to Carl, who described his intense feelings for Freud as a religious crush, their first conversation lasted thirteen hours. As for Freud, he believed that in Carl he had at last found his crown prince.

For a while this appeared to be so, as the master and student cooperated in developing their ideas of psychoanalysis, maintained a prolific correspondence, and traveled together, including to America. But tension lurked below the surface.

By 1910, cracks had appeared in their relationship. Freud expected Carl to behave as an obedient son and to unquestioningly accept his theories. When Carl had his own ideas, Freud treated him like a rebellious son.

One area in which they differed was spirituality. Carl believed that the religious impulse was both a key to understanding human experience and a potential source of healing. Freud wrote this off as unscientific. Carl chafed at his mentor’s paternalistic attitude, and what he saw as Freud’s rigid and rather dark focus on repressed sexual desire as the main lens through which to understand people:

Freud’s unconscious is like a cellar full of repressed desires and things unpleasant…My idea of the unconscious is quite different. It is a field of potential.

The final break came in 1913 when Carl published a book criticizing Freud’s theories and laying out his own broader view of the human psyche. The two men would never reconcile. Liberated, Carl was now free to develop his own theories.

Carl’s belief that people are—again, quoting Bill Wilson—more than intellect, emotion and two dollars worth of chemicals set him apart from most of his colleagues of the time, particularly in Europe. We are, he said, meaning-seeking, meaning-making creatures.

The least of things with a meaning is worth more in life than the greatest of things without it.

His own experiences, and those of his patients, convinced him that meaning was ultimately found in a mysterious force which animated and informed human life, and which “supports us when nothing else supports us.” This is Rufus Jones’ Beyond, Evelyn Underhill’s great Reality….what most of us, and Carl himself, usually call God.

To Carl, humanity’s basic pathology was a disconnect from this God.

I have treated many hundreds of patients. Among those in the second half of life—that is to say over 35—there has not been one whose problem in the last resort was not that of finding a religious outlook on life.

Carl’s heart-centered therapy placed a premium on personal, lived experience and archetypal spiritual quests like the hero’s journey. Healing came not through intellectually studying one’s neuroses and managing symptoms. For Carl, there was no going under, over or around a problem. You had to go through. And on this journey—which was always painful—you arrived at a deeper awareness of yourself, others and all of life.

There is no birth of consciousness without pain.

That birth of consciousness is the spiritual awakening that can only come through ego collapse at depth, as Wilson so eloquently stated. And this is not a one-size-fits-all journey, but one that every man and woman has to make for themselves.

Follow that will and that way which experience confirms to be your own. Your vision will become clear only when you can look into your own heart.

In childhood we all construct a self—what Jung called a persona—to face the world, manage anxiety and overcome our problems. Trouble arises when that self ceases to work. For many, that happens around midlife (hence the midlife crisis). Then we must embark on a journey in which we encounter a higher power and discover our true, capital-s Self—the us that is not holy but whole.

One of those who sought Carl out at midlife was an American businessman named Rowland Hazard. In the early 20th century, the primary treatments for alcoholism were medical. Rowland had tried them all. None worked. Desperate, he made two trips to Switzerland to see Jung, hoping the world-famous analyst could cure him. But on the second trip, Carl declared there was nothing more he could do. Rowland’s problem, he said, was not scientific or medical; it was spiritual. Rowland’s drinking was a form of spiritual thirst—a misguided search for wholeness and connection. His only hope was to have an encounter with a power higher than himself and, through that, find his true Self.

Carl’s prescription? Let go of the endless ruminating and get to some real, hands-on living. Maybe then, in service and through fellowship with others, Rowland would find release from alcohol, and the answers he was looking for.

The quest for such an encounter led Rowland to the Oxford Group, a Christian movement which centered personal change through the practice of what it called the Four Absolutes: absolute honesty, purity, unselfishness, and love. Rowland’s diligent practice of these principles, and the resulting ego collapse at depth, provided the breakthrough he’d long sought. At long last, he found sobriety.

Carl Jung’s belief that alcoholism was a spiritual problem seeking a spiritual solution spread through the Oxford Group. Over the next few years, many Oxford members gave up drinking. Then, in November 1934, Bill Wilson was introduced to Carl’s thought. Like Rowland, he too found lasting sobriety.

Soon, he took Carl’s ideas, merged them with Oxford Group principles, then added his own hard-won wisdom. The end-product was a 12-step program to help alcoholics quit drinking. It soon became, and remains to this day, the most successful addiction intervention in history. And it all started with Carl Jung’s straight talk to a patient in 1931.

Yet Carl knew none of this. It was only in January 1961 that Bill Wilson enlightened him about his historic role. He immediately composed an answer to this stunning news.

Jan. 30, 1961

Dear Mr. Wilson,

Your letter has been very welcome. I often wondered what had been [Rowland's] fate. Our conversation had an aspect of which he did not know. The reason that I could not tell him everything was that, in those days, I had to be exceedingly careful of what I said, for I was misunderstood in every possible way.

His craving for alcohol was the equivalent of the spiritual thirst of our being for wholeness--expressed in medieval language: the union with God. How could one formulate such an insight in a language that is not misunderstood in our days?Carl here is referring to his belief that human pathology comes from an unsatisfied spiritual thirst. He goes on in the letter to quote Psalm 41—As the heart panteth after the water brooks, so panteth my soul after thee, O God—then acknowledges that such language is easily misunderstood. Surely, Bill Wilson’s letter would have spurred memories of his disputes with Freud over spirituality.

The only right way to such an experience is that it happens to you in reality, when you walk on a path which leads you to a higher understanding. You might be led to that goal by an act of grace or through a personal and honest contact with friends, or through a higher education of the mind beyond the confines of mere rationalism. I see from your letter that Roland H. has chosen the second way, which was, under the circumstances, obviously the best one.

I am strongly convinced that the evil principle prevailing in this world leads the unrecognized spiritual need into perdition, if it is not counteracted either by a real religious insight or by the protective wall of human community. An ordinary man, not protected by an action from above, and isolated in society, cannot resist the power of evil, which is called very aptly the Devil. But the use of such words arouse so many mistakes that one can only keep aloof from them as much as possible.This is one of the most influential figures of the 20th century getting vulnerable with a new friend he’s never met but who he feels he can trust.

These are the reasons why I could not give a full and sufficient explanation to Roland H. But I am risking it with you because I conclude from your very decent and honest letter, that you have acquired a point of view above the misleading platitudes one usually hears about alcoholism.

You see, Alcohol in Latin is “spiritus” and you use the same word for the highest religious experience as well as for the most depraving poison. The helpful formula therefore is: Spiritus contra spiritum.*

Thanking you again for your kind letter.

I remain yours sincerely,

C.G. Jung

*(translation: Higher Power over alcohol)Carl Jung died only a few months after this exchange of letters with Bill Wilson.

While Sigmund Freud was, arguably, more prominent throughout the 20th century, interest in Jung has skyrocketed in the 21st. This is due in no small part to the fact that science is now proving what Jung was trying to tell people all along—that we are innately spiritual beings, and healthy spirituality very often corresponds to a host of positive outcomes, from better health to longevity to a feeling of greater purpose. Jung always knew this. He needed no studies. The proof was in his own life, and the lives of those he helped heal.

Asked in 1959 if he believed in God, he gave a classic Jungian response which will bring a knowing smile to the faces of all those, like Carl Jung, whose personal spirituality needs no explanation or “proof”.

I don’t need to believe. I know!

A note on the letters between Bill Wilson and Carl Jung

For purposes of space and clarity, I have edited and condensed the letters between Bill Wilson and Carl Jung. You can read Wilson’s letter in its entirety here. Read Jung’s letter in its entirety here.

Practice

I love this quote from Jung:

Often the hands will solve a mystery that the intellect has struggled with in vain.

This reminds me of two things:

Spiritual life is not theory; it must be lived.

One of the most healing things we can do is to just get out and live each day with loving presence.

So, for today’s practice, consider one of the following: take a walk and really pay attention; engage in a contemplative practice; call up, or share time with, a friend (remember that Jung prescribed to Rowland Hazard personal and honest contact with friends); perform an act of service for a loved one; prepare a meal mindfully; do charity work; engage with a group that fosters spiritual growth. The list goes on and on.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

All in-person gatherings are at 205 East Monroe Street in Austin, Texas.

Sun. Dec. 8, 11:15am: LITC's original holiday musical, Make Room In Your Heart. Sat. Dec. 21, 6:00pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate gathering on the longest night. Mon. Dec. 23, 6:00pm: Christmas Eve-Eve candlelight service...an LITC tradition! Sun. Dec. 29, 11:15am: Welcome 2025 with a fun casual service that includes, coffee, cookies, conversation and resolution-setting.

Contemplation In The City

Life In The City’s contemplative community meets regularly to practice sacred traditions like Lectio Divina and Centering Prayer. If you’re in Austin, consider joining us. Upcoming gatherings are Jan. 14, Feb. 4, Mar. 4, Apr. 8, May 6. We meet at 205 East Monroe Street in Austin. Doors open at 6pm for coffee and conversation, service from 7-8pm. . You might also enjoy our monthly newsletter in which we wrestle with how to live a spiritually-engaged life in the modern world. Read more here.

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2022 edition, to find out how my experience of September 11, 2001 became my gateway to Advent.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Catch a typo? Have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets for a future year? Leave feedback in the Comments below or email Greg Durham at greg@litcaustin.org.

This is a lovely post, thank you for it.

Greg, each of your communications this year are speaking right into my heart. The discussion about Jung's struggle with the scientism of early twentieth century medicine comforts me having struggled with same.