We become what we love.

Advent Day 17: Clare of Assisi (1194-1253)

The first time she saw him was at church during Lent. He was a magnetic figure: handsome, free-spirited, confident. Afterward, she couldn’t stop thinking about him—his voice, how he dressed, the things he said. All she wanted was to see him again. But there was no point asking her parents. They would never let her. So, she devised a plan. She wrote a message and passed it to a friend who knew someone who knew someone who knew him. Meet me at the chapel of St. Mary, Palm Sunday, midnight.

While the town slumbered on Palm Sunday, she crept from her family palace. Traveling under cover of dark, she crossed fields and ducked through orchards. When she finally reached St. Mary’s, he was there waiting for her in the flickering light of the altar candles.

Despite the romance novel set-up, this is not nearly as sexy as it sounds, because a) this is Francis and Clare of Assisi we’re talking about and, b) rather than planning to elope they were plotting how to join forces to serve the poor and outcasts of their town. Also this: when dawn broke over the Italian hills, Francis didn’t spirit Clare off to a Tuscan villa, he walked her to the local convent.

When they found out, Clare’s parents were hardly less angry than if she had eloped. In fact, they were probably angrier. Their daughter had forsaken her inheritance and the life to which she was entitled (i.e. obligated)—marriage to a wealthy man and as many kids as she could produce—to cavort with a mystic. And not just any mystic, but Francis, the ne plus ultra of holy foolery.

That same day, Clare’s parents, accompanied by a few of Clare’s would-be suitors, formed a little mob and went to drag her out of the convent. But Clare—already dressed the part of a nun—managed to get loose. In a dramatic display, she tore off her veil to reveal that her flowing blonde locks were gone, replaced by a choppy Weird Barbie wedge cut. Apparently, lopping off your locks was the ultimate sign you rejected mainstream values, if you were a rich girl in the 12th century (or the 21st…see: Britney Spears). Shocked and disappointed, Clare’s parents departed in disgust.

It had only been a few years since Francis, himself, had forsaken his wealthy family, donned the coarse brown habit worn by the poor, and begun wandering the countryside preaching the good news of Jesus, healing the sick and feeding the hungry. Since then he’d attracted a sizeable following of men. Enough, in fact, that the pope had granted them permission to form an order (now called the Franciscans).

Francis was eager to see women get in on the act, too. The only problem: he needed someone with a heart for service, the desire to conform to the life of Christ, uncommon intelligence and spiritual depth, and strong organizational skills. He’d met plenty who’d had some of these traits, but none who had all. Until Clare. In the years to come, the two would form one of history’s great spiritual partnerships. Like Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross, each needed who the other was in order to fulfill their spiritual vision, and each found in the other a friend and confidante.

Clare set up shop next to the church at San Damiano, which Francis had rebuilt with his own hands. She called the new order The Poor Ladies. In keeping with the Franciscan lifestyle, her days were organized around work and prayer. She went barefoot, slept on the ground, ate no meat, and kept almost completely silent. This does not sound like a winning business plan. And yet, Clare was soon joined in her new venture by many others, including her sister, who were attracted to her obvious spiritual purpose and joy.

Though Clare was excellent at leading, she never got completely comfortable with it. She had no interest in power or official titles. As such, when she referred to herself, it was often as a handmaid or servant. She hated giving orders. Because she saw her vocation as caring for others, she usually saved the hardest jobs for herself.

The core tenant of the Poor Ladies’ Rule (a religious order’s governing principles), as the name would imply, was poverty. But staying poor was a struggle, for in Clare’s day convents were popular repositories for the donations of wealthy families, ensuring the donors’ place in heaven. Or so the thinking went. For Clare this meant fending off constant offers of money and goods, in order to keep the other nuns’ eyes on the prize of the simple life.

Clare’s singular purpose was to imitate Christ. This meant centering love in every thought, action and intention. And not just showing love, but—like Jesus—being Love.

We become what we love and who we love shapes what we become. Let the love you have in your hearts be shown outwardly in your deeds.

This kind of love was entirely other-centered, a supreme identification with the needs of those around her. And those around her she saw as both a microcosm of the world and the imago Dei of Jesus. When she fed a beggar who came to her door, she fed the world and God. Clare had a gospel worldview, and the way she saw things, what she did for the least of these, she did for Him.

It goes without saying that this kind of life came with much trial. But for Clare, suffering much was her assurance that she had loved much.

Love that does not know suffering is not worthy of the name.

As the years passed, Clare and Francis’s mutual respect and admiration grew. For Clare, Francis was as close to a Christ-like figure as she ever expected to meet. For Francis, Clare was his “woman of my castle”, who embodied the highest Franciscan ideals.

In the 1220s, when Francis began to suffer from poor health, he increasingly leaned on Clare for counsel and spiritual comfort. During a particularly rough patch, he built a little hut next to her convent to be close to her. Here he composed one of his most famous songs, The Canticle of Brother Sun and Sister Moon. In his vivid imagery, praising Sister Water for being useful and humble, Sister Mother Earth for sustaining him, and Sister Moon for shining clear and precious, it’s easy to spot Francis’s feelings about Clare, his Sister in Christ who embodied all those virtues he saw mirrored in creation.

Clare helped care for Francis in his final illness. She knitted him clothing when it was cold, she sent him food when he was hungry. When Francis died in 1226, she and the rest of the community was distraught.

We (took) note . . . of the frailty which we feared in ourselves after the death of our Francis. He who was our pillar of strength and, after God, our one consolation and support.

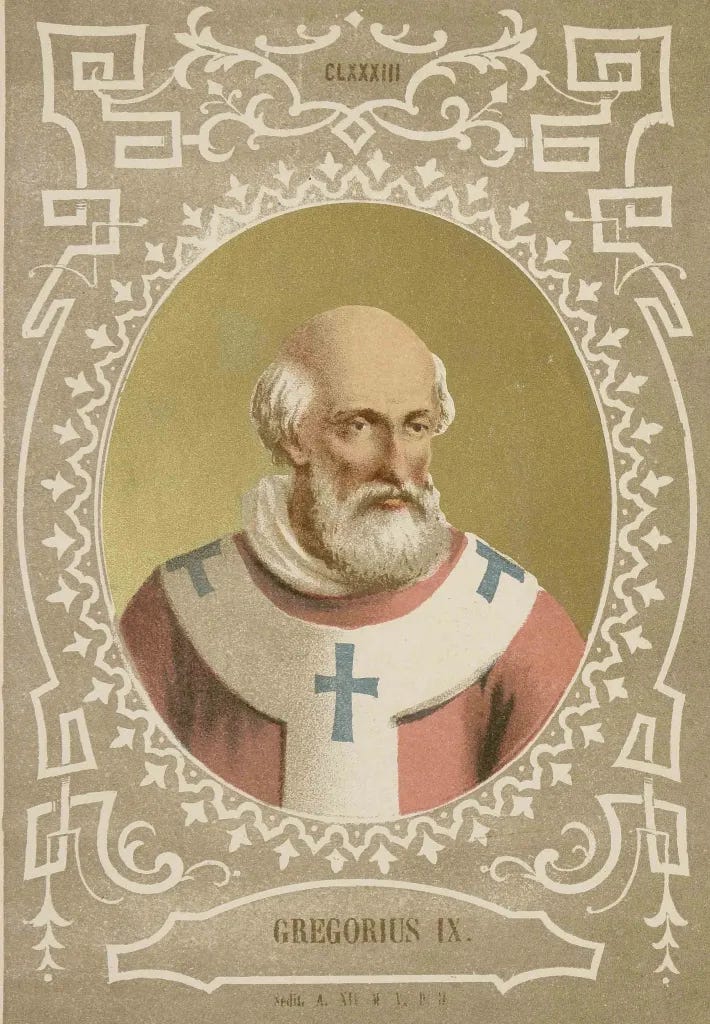

In the years ahead, Clare worked hard to sustain and grow her order. One of her most significant challenges came when the Pope tried to enforce a common rule on all religious orders. This would have meant giving up her Rule of poverty. Pope Gregory IX was opposed to it out of kindness: he was concerned it was having a negative impact on the health of Clare and the other nuns. He even paid Clare an in-person visit to convince her to treat herself a little nicer. Clare would have none of it.

Absolve me from my sins, Holy Father, but not from my wish to follow Christ.

Seeing she could not be moved, Gregory let Clare keep her poverty. But she now realized she needed to write and codify her own, more extensive Rule for her order. The final document, modeled after Francis’s Rule, emphasizes the non-possession of property, in imitation of Christ.

I admonish and exhort all my sisters, both those present and those to come, to strive always to imitate the way of holy simplicity, humility, and poverty.

This was officially approved by the pope the day before Clare’s death. It was the first Rule ever written by a woman, and remains the Rule for the order to this day.

Like Francis, Clare suffered a lengthy physical decline. In her last days, she was overheard speaking to herself:

Go forth in peace, for you have followed the good road. Go forth without fear, for he who created you has made you holy, has always protected you, and loves you as a mother. Blessed be you, my God, for having created me.

She died on August 11, 1253, at the age of fifty-nine. In her honor, the order she founded was renamed The Poor Clares.

Advent Practice

Spiritual friendship and fellowship were vital to Clare. This showed up most significantly in her relationship with Francis. But she also had other mutually enriching friendships that fostered her faith, including with Agnes of Prague.

For today’s practice, read the below excerpt from a letter Clare wrote to Agnes. Like Clare, Agnes had forsaken the life of luxury for one of poverty and service. Here Clare offers her friend a blessing for courage in the face of those who thought she was crazy for choosing the simple life.

What you hold may you always hold.

What you do, may you always do and never abandon.

With swift pace, light step and unswerving feet,

so that even your steps stir up no dust, go forward.

The spirit of our God has called you.

Now reflect on someone in your life, living or dead, who has been a guide along your spiritual path. Write out a blessing or say a prayer of gratitude for them.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

Dec 21, 7 pm: Blue Christmas contemplative service for the darkest night of the year.

Dec 23, 6 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve candlelight service, an annual LITC tradition.

Dec 24, 11:15 am: LITC’s regular Sunday service.

Dec 31, 11:15 am: A fun, casual service with cookies and coffee to welcome 2024.

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2023 edition of The Heart Moves Toward Light: Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Did you catch a typo? Do you have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets we might cover in the future? Leave feedback in comments section below or email Greg Durham at greg@lifeinthecityaustin.org.

"For Sister Poverty, we give thanks. For Brother Want, we give thanks." I love the dynamic between St. Francis and St. Clare. Their love for each other, which I suppose is ultimately a love for the Way of Jesus, is inspiring - especially in a world where some powerful, influential men feel like they can't have close female companions without being corrupted or tempted or something. I love the way you painted the scene of him marching her down to the covent after their "romantic" encounter at St. Mary's. I cracked up as I read it early this morning.