Advent Day 19: Pauli Murray and Eleanor Roosevelt

Symbols of healing

Hope is a crushed stalk between clenched fingers. Hope is a song in a weary throat.

Advent Day 19: Pauli Murray (1910-1985) and Eleanor Roosevelt (1884-1962)

Their friendship began as a confrontational letter from a young activist to the most famous woman in the world, the First Lady of the United States.

It was 1938 and Pauli Murray’s application to the University of North Carolina law school had just been denied because she was black. Rather than take the rejection lying down, she went on a public relations blitz, planting stories in the press and writing letters, including to President Franklin Roosevelt. To increase the odds of the President seeing her letter, she sent a copy along with a cover letter to Eleanor Roosevelt who she had once met at a WPA camp for women in New York state:

December 6, 1938

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt:

You do not remember me, but I was the girl who did not stand up when you

passed through the Social Hall of Camp Tera during one of your visits in the

winter of 1934–35. Miss Mills criticized me afterward, but I thought and still feel that you are the sort of person who prefers to be accepted as a human being and not a human paragon.

One of my closest pals is “Pee Wee,” whom you know as Margaret Inness. I have watched with appreciation your interest in her struggle to improve herself and to secure employment. Often I have wanted to write you, but felt that you had more important problems to consider. Now I make an appeal to you in my own behalf.

I am sending you a copy of a letter which I wrote to your husband, President Roosevelt, in the hope that you will try to understand the spirit and deep perplexity in which it is written, if he is too busy.

I know he has the problems of our nation on his hand, and I would not bother to write him, except that my problem isn’t mine alone, it is the problem of

my people, and in these trying days, it will not let me or any other thinking

Negro rest. Need I say any more?

Sincerely yours,

Pauli MurrayTo Pauli’s surprise and delight, Eleanor responded. Though the reply was respectfully reserved, there was a telling detail: it arrived on Eleanor’s personal letterhead, signaling a particular interest in what Pauli had written to her. Proof of this came two days later when Eleanor, in her popular My Day column which reached millions of Americans, paraphrased Pauli’s words from her letter to the President:

Are you free if you cannot vote, if you cannot be sure that the same justice will be meted out to you as to your neighbor; if you are expected to live on a lower level than your neighbor and to work for lower wages; if you are barred from certain places and opportunities?

It was the start of a friendship that would last decades and profoundly change both women.

Pauli Murray was born in 1910 and raised in North Carolina. Like so many Americans, she was of mixed ancestry: slave and slave owner, Irish, Cherokee. Feeling the presence and pull of all these ancestors in her blood, she often referred to herself as biologically and psychologically integrated. But no matter how integrated Pauli felt in her soul, both Jim Crow and Jane Crow—a term Pauli coined to describe policies of sex discrimination—insisted on segregation. These laws dictated where and how she could live, and what opportunities she was afforded (and denied). In Pauli, however, Jim and Jane Crow faced a formidable foe.

Pauli always felt she was meant for big things. But living her destiny meant escaping the segregated South. In 1926, she moved to New York City and attended Hunter College, one of four Black students in a class of two hundred forty-seven. By the time she graduated, however, the world was mired in the Great Depression. Jobs were few, especially for a skinny black girl who people often confused for a boy.

During the Depression, Pauli fell in love for the first time, with Peg Holmes, a young white woman from an affluent family. Together, they scratched out a meager existence on odd jobs, camping in woods and on beaches. Like so many others, they found themselves drawn to the social movements sweeping America. At rallies for workers’ rights, Pauli began to think about freedom and dignity, not just as they concerned particular movements, but in all aspects of her life—as a black person in a segregated society, as a woman shut out from many jobs and institutions, and as a person whose sexual orientation lived outside the mainstream.

As the 1930s marched on and economic conditions slowly improved, Pauli felt called to make a difference in the world. The best avenue for that, she believed, was the law where she would be able to combine her prodigious energy with her sweeping mind and writing talent.

In 1938, she applied to the University of North Carolina but was denied due to her race. The rejection was a turning point.

Incident after incident piling up meant that sooner or later I would either go berserk or I would find a way to protest.

Pauli developed a strategy she would employ again and again throughout life, combining literary talent and courage to try and right wrongs. She called this strategy confrontation by typewriter.

Her first letter to Eleanor Roosevelt was part of this strategy in the UNC case. Though she was ultimately unsuccessful in entering UNC, it initiated her long and fruitful friendship with the First Lady.

Despite their differences of age, upbringing and circumstance, Pauli and Eleanor shared much in common, which biographer Patricia Bell-Scott details in her book The Firebrand and the First Lady,

They shared the given name Anna, which neither preferred or used. Both lost their parents as children and were raised by elderly kin. Highly sensitive, they had an abiding compassion for the helpless that stemmed in part from their childhoods as orphans, their experience with chronically ill relatives, and their need for acceptance... They were both baptized as Episcopalians and remained lifelong congregants. They had inquiring minds. They were voracious readers. They loved poetry, and they loved to write. They were unpretentious, and they conveyed a seriousness of purpose that made them seem humorless, which was not the case. Both endured ridicule—Murray for her boyish physique, ER for her protruding teeth. They had presence and phenomenal energy. They rarely slept more than five or six hours a night. ER’s daily schedule left those around her breathless, and Murray’s intensity exhausted even her most patient friends.

In 1940, Pauli landed in the news again for refusing to move to the back of the bus in Petersburg, Virginia. Three years after that, now studying at Howard University Law, she was, once more, shaking things up by leading lunch-counter sit-ins at a popular D.C. restaurant. Note that these actions occurred, respectively, fifteen years before Rosa Parks was arrested, and seventeen years before student activists desegregated Woolworth lunch counters. As with most mystics and saints, Pauli lived out on the frontiers of life. And like one of her favorite prophets, John the Baptist, she was blunt, clear-eyed and no-nonsense.

After finishing first in her class, Pauli was entitled to continue studies at Harvard Law which, every year, granted automatic admission to the top Howard graduate. However, Pauli was denied entry because Harvard did not yet admit women. Instead, Pauli went to the University of California in Berkeley after which she began a groundbreaking career.

Pauli’s list of accomplishments is staggering. She was the first Black assistant attorney general in California history. Thurgood Marshall used the arguments she laid out in her book States’ Laws On Race And Color to build his challenge against separate-but-equal policies in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case. And in 1961, President Kennedy appointed her to his Commission on the Status of Women, chaired by her good friend Eleanor Roosevelt.

Through all this, Eleanor was ever-present in Pauli’s life, providing support, counsel and connections. They exchanged hundreds of letters and cards, spoke often on the phone, and met whenever they could, often at Eleanor’s home in upstate New York where they could be away from the prying eyes of the press and public.

For Eleanor, Pauli was a daughter-figure, a prophet from the younger generation, and a restless social justice warrior who prodded her to take stronger public stances on the values they shared, particularly as it regarded racial discrimination. My firebrand, Eleanor affectionately called her. As for Pauli, Eleanor was a combination of wisdom master and surrogate mother, a tempering influence and elder whose status as a global icon for human rights helped her gain a deeper understanding of human nature and the value of working to build coalitions. According to Patricia Bell-Scott,

They developed an enduring friendship that came to be characterized by honesty, trust, affection, empathy, support, mutual respect, loyalty, acceptance, a commitment to hearing the other’s point of view, pleasure in each other’s company, and the ability to pick up where they’d left off, irrespective of the miles that had separated them or the time lapsed.

Eleanor’s sudden illness in late 1962 blindsided Pauli. On October 11, Eleanor’s seventy-eighth birthday, Pauli spoke at a conference of the National Council of Women. After, she wrote her last letter to her dear friend who was sequestered in the hospital with tuberculosis. The letter first updated Eleanor on the conference and other news, then turned into a loving, personal tribute:

For many years you have been one of my most important models—one who combines graciousness with moral principle, straightforwardness with kindliness, political shrewdness with idealism, courage with generosity, and most of all an ongoingness which never falters, no matter what the difficulties may be…you are the very embodiment of a woman of conscience…

Knowing that you are “laid up” we shall be working doubly hard to carry on, following in your footsteps, for almost every achievement of women active today is a spiritual vote for Eleanor Roosevelt. I do not exaggerate. My love…

Pauli Eleanor died a few weeks later. Pauli was among a select group of those to attend her funeral. Though devastated, she was determined to keep burning the candle she said Eleanor had lit in her heart.

This fire led to her co-founding, in 1966, the National Organization of Women. Then, in 1971, she was named co-author of Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s brief in Reed v. Reed, the groundbreaking case that extended the 14th amendment’s equal protection clause to women. By her early sixties, Pauli had achieved tenure as a professor of law and politics at Brandeis University. As Pauli put it, she had lived to see her lost causes found. But she wasn’t yet done making waves. Soon, her restless energy and desire to push ever deeper led her to a move that shocked friends and family: she entered seminary.

For Pauli, religion wasn’t a left turn but a logical move deeper into her life’s work. Fighting racism and sexism had never been about changing laws as much as changing hearts. It had been a spiritual quest to move America closer to the principles espoused not only by its Constitution but the gospel of Jesus which most Americans professed to believe. The way Pauli saw it, if America was to continue moving forward, it needed healing and reconciliation. It needed God.

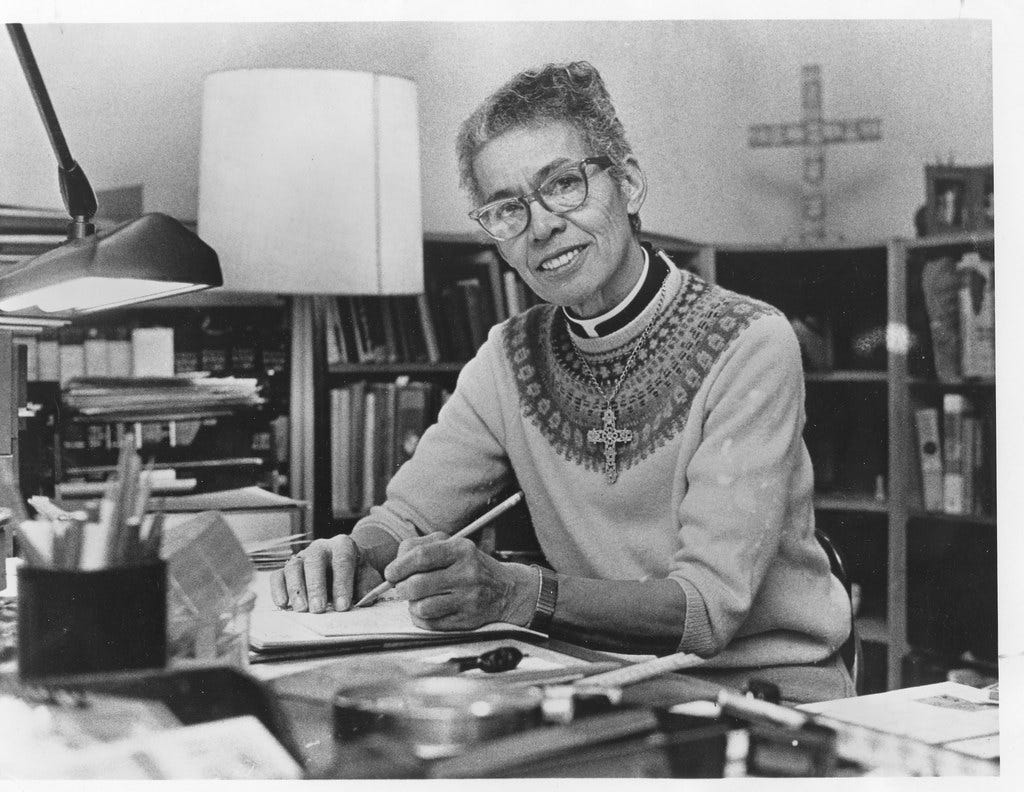

In 1977, she became the first Black woman ordained as an Episcopal priest.

Whatever future ministry I might have as a priest, it was given to me to be a symbol of healing. All the strands of my life had come together. Descendant of slave and of slave owner, I had already been called poet, lawyer, teacher, and friend. Now I was empowered to minister the sacrament of One in whom there is no north or south, no black or white, no male or female—only the spirit of love and reconciliation drawing us all toward the goal of human wholeness.

Though Eleanor Roosevelt did not live to see the incredible accomplishments of Pauli Murray’s last two decades, Pauli carried her spirit into everything she did. This was an Advent spirit which she and Eleanor shared, that what goodness we can’t yet see or imagine is not only possible, but is already on its way.

Practice

Pauli Murray and Eleanor Roosevelt were supremely hopeful women. In true Advent fashion, both believed that a new day was always dawning. Such sustained hopefulness took courage, resilience and practice, and would not have been possible without their deep belief in reconciliation.

Where in your life are you seeking reconciliation? What relationships have you put on autopilot, or let go of, that you would like to revive?

For todays practice, pick a relationship, whether friend, family or community, and commit to breathing new life into it in 2025. Write down one action you will take to make this happen (e.g. go to coffee with an old friend, return to church, call a sibling you haven’t talked to in a long time, etc.). Post this plan-of-action somewhere you will see it until the action has been implemented.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

All in-person gatherings are at 205 East Monroe St. in Austin, TX.

Dec. 8, 11:15 am: LITC’s original musical, Make Room In Your Heart. Dec. 21, 6:00 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the longest night. Dec. 23, 6:00 pm: Our annual Christmas Eve-Eve service. Dec. 29, 11:15 am: Welcome 2025 with a fun, casual service that includes coffee, cookies, conversation and resolution-making.

Contemplation In The City

Life In The City’s contemplative community meets regularly to practice sacred traditions like Lectio Divina and Centering Prayer. If you’re in Austin, consider joining us. Upcoming in-person gatherings are Jan. 14, Feb. 4, Mar. 4, Apr. 8, May 6. We meet at 205 East Monroe Street in Austin. Doors open at 6pm for coffee and conversation, service from 7-8pm. You might also find meaning in our monthly newsletter in which we wrestle with how to live a spiritually engaged life in the modern world. Read more here.

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2022 edition, to find out how my experience of September 11, 2001 became my gateway to Advent.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Catch a typo? Have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets for a future year? Leave feedback in the Comments below or email Greg Durham at greg@litcaustin.org.

Two of my sheroes! How did I not know of their friendship?! Thanks for another inspiring chapter for your book! ;-)

I had never heard of Pauli Murray. What a wonderful story and inspiration!