The truth is powerful and it will prevail.

Advent Day 4: Sojourner Truth (1797-1883)

Most of us can point to moments in our lives—a day or period we can later look back on and say that who we were after is not who we were before. These moments arrive welcome and unwelcome, as joy and tragedy, as decisions long-deferred finally made, as epiphanies received.

For Belle Van Wagenen, that moment came on June 1, 1843: Pentecost Sunday.

Belle was forty-six year old. Even by the standards of a time when the sheer act of living involved risk and adventure unimaginable to most of us today, she’d led an epic life. Born into slavery in upstate New York, at age twenty-nine she’d had the courage to walk away from her master. She’d later sued another slaveholder who, in violation of federal law, had taken her son to Alabama. She won, becoming one of the first black women in America to prevail in court against a white man. Later, at the encouragement of fellow Methodists, and with a deeply felt need to serve others, she left her native Catskills for crowded New York City where, among other missions, she worked at a halfway house for former prostitutes.

She’d lived so many lives. Yet by 1843 she was depressed and discouraged she hadn’t lived the one she knew was her true calling: to awaken people to the gracious, loving and merciful God she knew—a God who was one with all people and all of creation.

Now here she was, remembering the Pentecost story when the Spirit, in a blaze of fire and wind, broke down the walls of culture and language, granting Jesus’s disciples the courage to go out into the world and spread the good news: freedom for the oppressed, sight for the blind, release for the spiritual captives. Belle folded her hands, closed her eyes and began to pray that the same Spirit-fire might touch her.

Prayer had always been important to Belle. Her mother, Mau-Mau Bette, had taught her to always pray—in the morning and evening, during work and rest. Mau-Mau said, if Belle kept her mind fixed on God then everything was prayer…how you walked and talked and breathed. Your life was a prayer! And it was always important to share with God what was on your heart like you would a friend. God might not save you from your troubles, but God would sustain you through them in ways mysterious and unsayable. The important thing was to never let go of that thread that connected you to God.

Now, as Belle prayed, she heard a still, small voice whisper, “Go east.” She listened harder, to be sure she’d heard right. Then there it was again: “Go east.”

That was the word. East it would be!

But if she was going to be traveling into a whole new life, she’d want a whole new name to take with her. As she prayed on that, a word came to her from Psalm 39:

Hear my prayer, O Lord, and give ear unto my cry…for I am a stranger with you, and a sojourner, as all my fathers were.

Sojourner. That was it! For that’s what she would be: a sojourner spreading God’s love.

She left New York City that very day, carrying all her worldly possessions in a pillowcase. That afternoon, stopping by a Quaker farm for a drink of water, the woman of the house asked her name. Sojourner, Belle answered. The woman asked her last name. Belle hadn’t thought of this. She’d had multiple last names in her life, most of those from men who’d owned her. Now she had the freedom to name herself.

She said a quick, silent prayer. A word came back: Truth.

It was perfect. God was Truth and she was being called out to preach the Truth.

“I’m Sojourner Truth,” she told the woman.

That summer evening in 1843, she could have had no idea how famous that name would become.

Sojourner spent summer 1843 wandering east through Long Island then north into Connecticut. Often, she found company among the Millerites, a millennial movement that had predicted Jesus would return on October 22, 1844. In preparation for that day, many Millerites had given away all their possessions and were living in communal camps. Sojourner was not a Millerite, but they were one of the only racially integrated religious groups in America who also welcomed women preachers.

Before long, word of the striking, six-foot tall woman with the prophetic name, commanding voice and common touch preceded her. Now when she came into a new camp, she found she was already famous.

Many Millerites were terrified about Jesus’s return. Would they be among the saved? What would the world be like after God punished the wicked?

One night in Hartford, Sojourner listened to some preachers work the people into a lather of fear, howling at them that they’d better get right with God before it was too late. This saddened Sojourner. Her heaven was not later and up there. It was here and now. And her God was Love, not fear. Didn’t Jesus say to love God with all your heart? Who ever loved anything more because they feared it?

When the men finished, Sojourner stood up and offered her alternative vision:

You think you are going to some parlor away up somewhere, and when the wicked have all been burnt, you are coming back to walk in triumph over their ashes. This is to be your New Jerusalem? I can’t see anything very nice in that…If God comes and burns the world the way you say he will, I am going to stay here and stand the fire. Jesus will walk with me through that fire and keep me from harm. Nothing belonging to God can burn any more than God himself.

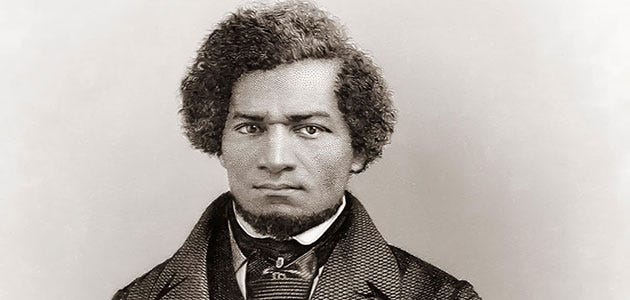

By autumn, Sojourner had made her way to Northampton, Massachusetts where she joined a socially progressive commune. The impact of this place on Sojourner’s life cannot be understated, for here she rubbed shoulders with famous abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and Frederick Douglass, and women’s rights advocates Helen Benson and Olive Gilbert. The freethinkers in the commune treated her as an equal, and quickly realized that Sojourner could be a powerful tool in their fight for human rights.

In Northampton, Sojourner fully merged her spirituality with her desire to help people and change the world for the better. With her lightning wit and folksy humor, she earned a reputation as someone who could soften even the most hardened opponent. And sometimes the “opponent” might even be on her same side of the issues.

Sojourner had an uncompromising vision of the kingdom of God. The cornerstones of that vision were peace, love, nonviolence, and dignity for all including even slaveholders. If anyone ever deviated from those principles in her presence, she was quick to let them know what she thought. No less than Frederick Douglass discovered this when Sojourner frequently called out what she saw as flaws in his thinking, leading Douglass to later describe her as

…a strange compound of wit and wisdom, of wild enthusiasm and flint-like common sense…who seemed to feel it was her duty to trip me up in my speeches...

Countless descriptions of Sojourner have been left behind, including from famed novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe who moved among the luminaries of the age, and who said,

I never knew a person who possessed so much of that subtle, controlling power called presence as Sojourner Truth had.

But the best description of Sojourner’s superpowers comes from the woman herself:

I can’t read a book but I can read people.

In 1850, Sojourner stepped onto the national stage first by publishing her memoir which became a surprise hit, then at a large, national antislavery convention in Boston. There, she spoke to thousands of spectators as well as journalists from around the country who reported that she brought the house down with her speech against slavery and for women’s rights. Only seven years after her Pentecost prayer that God might help her live her calling to help others, Sojourner Truth had found her groove.

The 1850s was a decade of intense social ferment. Not only was the rupture over slavery racing toward reality, but women were growing ever more bold in demanding their rights. Sojourner was on the front lines, combining both struggles into a singular fight. She did this in convention halls, churches and newspaper editorials (dictated, as she never learned to read and write). She drew audiences both friendly and hostile. And though she usually avoided being attacked by disarming with humor those who would do her harm, occasionally she was not successful. One beating in particular left her with a permanent limp.

Today she is most remembered for an 1851 speech given at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. On this day she rose to a standing-room-only crowd and in simple, vivid prose wrecked the justifications of those in the audience who resisted equal rights for all.

To the point that women were the weaker sex:

I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed. Can any man do more than that?

Of her mind:

All I can say is, if a man has a quart and a woman has a pint…(here Sojourner is challenging the widely-held belief that men were smarter because their brains were larger), why can’t she fill up her little pint?

The solution to all this fuss was simple:

The poor men seem to be all in confusion and don’t know what to do. Why, children, if you have woman’s rights, give them to her and you will feel better. You will still have your own rights and they won’t be so much trouble.

Sojourner pointed out that a win-win was possible: by giving slaves and women their rights, they would be free, and the white men would also be freed from the soul-crushing, soul-corrupting work of denying those rights.

Sojourner finished by bringing it back to God:

How did Jesus come into this world? Through God who created him and woman who bore him. Man, where was your part?

Sojourner’s speech was widely distributed through the press and entered legend twelve years later when her friend Frances Gage published her recollection of the speech.*

Over the next three decades, Sojourner rarely slowed down as she continued working for peace, justice, mercy and love. She met three Presidents, including Abraham Lincoln who invited her to the White House several times. After the Civil War she lived in DC to care for refugee former-slaves and former soldiers. She lobbied Congress during Reconstruction. Ninety years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus, she regularly flouted DC’s segregation laws by riding the street car in the white section. After moving to Battle Creek, Michigan, she tried over and over to vote, but was always denied due to her gender. And years before it became a mainstream stance, she marched against capital punishment.

She also sat regularly for photographers, as pictures of her had become a popular collectors item, and a source of income (most of which she gave away). When asked why she did this she replied that she sold the shadow to support the substance.

In her last years she was pained to see civil rights in the South rolled back and replaced by a new kind of slavery called Jim Crow. Another source of pain: the women’s movement that was so close to her heart, and which had been so linked to the antislavery movement, was fracturing as some of its leaders feared that their support for the unpopular cause of voting rights for black men was jeopardizing their own chance of gaining voting rights.

In her last days, as word got out she was dying, friends, neighbors and reporters made pilgrimage to her home, all hoping for one last satiric quote, one last flash of wisdom. From her bed, Sojourner sang hymns and preached, though her voice was now weak. Like prophets of all times and places, her heart and soul had ascended a mountaintop, but her body would not get to enter the promised Land of universal dignity and freedom. Yet nothing could shake her belief that, in God’s kingdom—which she fervently believed was here and now—all were one, and good would eventually win.

As she weakened, she comforted those to whom she’d been a force, an anchor, a guru and wisdom mother. She wasn’t afraid to die. Death would be just like stepping out of one room into another…like stepping into the light. Now her work would be taken up by others. In the end, bad would always fail, she said, while good and truth would prevail.

She proclaimed this belief not long before her death, in a New Year’s greeting she offered the readers of one Chicago newspaper. The vision she expressed in this greeting is as simple, profound and relevant now as it was then:

God is without end and all that is good is without end. We shall never see God (until) we see him in one another. He is a great ocean of love and we live and move in him as the fishes in the sea, filled with his love and spirit, and his throne is in the hearts of his people. Jesus will be as we are, if we are pure, and we will be like him. There will be no distinction. He will be like the sun and shine upon us, and we will be like the sun and shine upon him, all filled with glory. We are all the children of one Father, and Jesus will be one among us. We will all be as one.

*A postscript on Sojourner Truth: The 1851 Akron speech has been immortalized as the Ain’t I A Woman speech. This comes from a memory of the speech published in 1863 by Truth’s friend and convention organizer Frances Gage. In this recollection, Truth repeats the refrain “Ain’t I a woman?” several times. However, neither the first transcript of the speech, made on the day it was given—and from which I’ve taken the quotes used in this chapter—nor eyewitness testimony published at the time make mention of this refrain. Today, Truth’s biographer Nell Irvin Painter, as well as most scholars, believe this was either a purposeful embellishment by Gage, or a catchphrase Gage heard Truth use in other settings that she then conflated with the Akron speech. That said, all versions of the speech agree on the salient points Truth made that day.

Practice

For Sojourner Truth, there was no separation between faith and social concern. If you had faith, it stood to reason you would make the world a better place through your acts of intentional lovingkindness.

In the Christian tradition, faith and works go hand-in-hand, following the model of Jesus and expressed by Paul in his letter to the Galatians,

The only thing that counts is faith working through love.

In other words, faith is not the end, love is. Faith is merely a means to reach love’s end. Or, as John Wesley put it, faith is only the handmaiden of love.

Today reflect on how, in the new year, your faith can serve as fuel for increasing the love you show. The field is wide open. It doesn’t have to look like showing up to protests or lobbying your politicians (though both are great and someone’s got to do those things). It can be as simple as bringing committed attention to a relationship with a friend or family member or even someone you might have a challenge with. It can look like being more present in one of the communities to which you belong and which you find purpose and spiritual sustenance. It can even be self-care in the form of developing contemplative practices.

Make a list of the areas where you’d like to grow your love. Then commit to taking an action in one of those areas before Advent is done.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

Dec 10, 11:15 am: LITC’s original holiday musical, Make Room In Your Heart.

Dec 21, 7 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the darkest night of the year.

Dec 23, 6 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve, an annual LITC tradition

Dec 24, 11:15 am: LITC’s regular Sunday service

Dec 31, 11:15 am: A fun, casual service with cookies and coffee to welcome 2024

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2023 edition of The Heart Moves Toward Light: Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Did you catch a typo? Do you have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets we might cover in the future? Leave feedback in comments section below or email Greg Durham at greg@lifeinthecityaustin.org.

It’s so interesting that she found company among the Millerites. Her compassion and love for God functioning as a foil to the mean-spirited tent preachers of her day is a good example for us during the upsurge of Christian nationalism.