Christmas is waiting to be born: in you, in me, in all mankind.

Advent Day 6: Howard Thurman (1899-1981)

Nearly all new life begins in dark. Seeds lie dormant in the earth before blossoming into wildflowers. A caterpillar sprouts wings in the solitude of a cocoon. Each of us reading this floated for months in a pitch-black womb before entering the bright world. Likewise, most of the marquee moments in the Advent and Christmas story occurred at night: Gabriel’s visit to Mary, Joseph’s dream, Jesus’s birth, the arrival of the magi, the flight to Egypt.

Howard Thurman, great Christian mystic and mentor to Martin Luther King, saw the dark—literal and metaphorical—as a friend of the soul. Darkness was so important to his spirituality, in fact, that he ascribed to it a quality often reserved for the most shimmering light: luminosity.

In his autobiography With Head And Heart, Thurman writes about the nights of his Florida childhood:

Nightfall was a presence. The nights in Florida…as I grew up…were not dark; they were black. When there was no moon, the stars hung like lanterns, so close I felt that one could reach up and pluck them from the heavens. The night had its own language…I could hear the night think and feel the night feel. This comforted me. I felt embraced, enveloped, held secure.

On these dark childhood nights, Howard Thurman found a light that radiated from within. That light became his inner authority and his Advent hope—hope not only that something new was at work in the world, but that he could be an instrument of the newness.

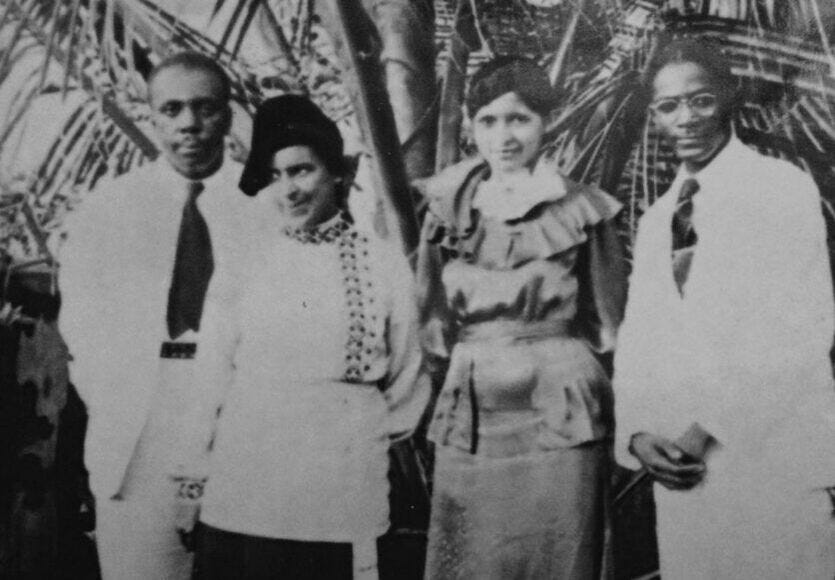

Born in 1899 in Daytona Beach, Howard’s childhood days were lived behind the high walls of segregation. But in the dark, those walls crumbled, and his imagination roamed beyond the gaze of Jim Crow, down the paths of possibility. His expansive sense of possibility eventually led him far from home.

At age thirteen—and with the encouragement of his grandmother, a former slave—he left Daytona for Florida Baptist Academy, one of only three private schools open to black children in Florida at the time. After graduation he attended Morehouse College in Atlanta then the Rochester Theological Seminary in New York, graduating valedictorian from both. From seminary, he took his first pastorate, in Oberlin, Ohio. It was there, in 1927, that Howard had, arguably, the most significant encounter of his life.

This occurred at a second-hand bookstore where he picked up Finding The Trail Of Life, a memoir by Quaker mystic Rufus Jones. In the few years leading up to this moment, Howard had increasingly felt the tension between what he saw as two stark choices—to lead either a life of engaged social action, especially in service to civil rights, or a contemplative life of prayer and pastoring. Jones, however, had little patience for either/or binaries. To him, life and, especially, spirituality were both/and propositions. Why choose either action or contemplation, Jones said, when your life would be infinitely richer and of service to the world by choosing action AND contemplation?

For Howard, this was a revelation:

[Rufus] had what I wanted, a combination of insight and social feeling.

After reading Finding The Trail Of Life, Howard decided that, though he hadn’t been in Oberlin long, he was going to move to Pennsylvania to study under the venerable Quaker.

In 1929, Jones and Thurman met for the first time and struck up a fruitful spiritual friendship. In sixty-six-year old Jones, Howard found a role model—a man who not only balanced the active and contemplative aspects of life, but one who was deeply rooted in his tradition while remaining open to wisdom and beauty wherever they were found. Likewise, Jones found in his twenty-nine-year old friend a profoundly gifted thinker and communicator who, more than any student he’d ever met, had the potential to make great change in the world.

In Howard’s year at Haverford, Jones opened three life-altering doors for him:

Jones introduced him to the Christian mystics, and in particular Francis of Assisi, Madame Guyon and Meister Eckhart. Eckhart’s words, that you can only spend in good works what you have earned in contemplation, left an especially deep mark on Howard.

He taught Howard that to find his own inner light he must take up daily contemplative prayer and meditation. For it is in the silent, luminous dark, Jones said, that you are best able to awaken to God.

Then, once awakened, Jones said, you had not only the ability but the responsibility to change the world for the better through non-violent action.

These were all key to Howard’s spiritual life, but this last rippled out into the world in ways neither could have then predicted.

In 1935, Howard’s interest in combining action with contemplation in service to the nascent American civil rights movement led him to travel to India to meet Gandhi, as Jones had done a few years earlier. There, the famed Indian leader expressed regret that, up to that point, the principle of nonviolent resistance had not caught worldwide interest. He challenged Howard to dig into the gospels to develop a Christian philosophy of nonviolence. If he could do this, Gandhi said, then perhaps it would be through the black struggle in America that the world would finally come to know peaceful resistance.

Understanding that any peaceful movement hoping to destroy segregation would require deep inner discipline and an ability to transcend fear, suspicion and hatred, Howard spent the next fifteen years studying Jesus’s resistance to the Romans and the ruling elites who’d been corrupted by Rome. This culminated in his groundbreaking book Jesus and the Disinherited which laid the moral framework for the modern American civil rights movement. If this movement was to succeed, Howard ultimately concluded, it would have to be grounded in love.

The religion of Jesus makes the love-ethic central. Every man is potentially every other man’s neighbor. Neighborliness is nonspatial; it is qualitative. A man must love his neighbor directly, clearly, permitting no barriers between.

This was no easy matter for Jesus and his followers who faced opposition from all sides.

A twofold demand was made upon [Jesus] at all times: to love those of the household of Israel who became his enemies because they regarded him as a careless perverter of the truths of God; [and] to love those beyond the household of Israel—the Samaritan, and even the Roman.

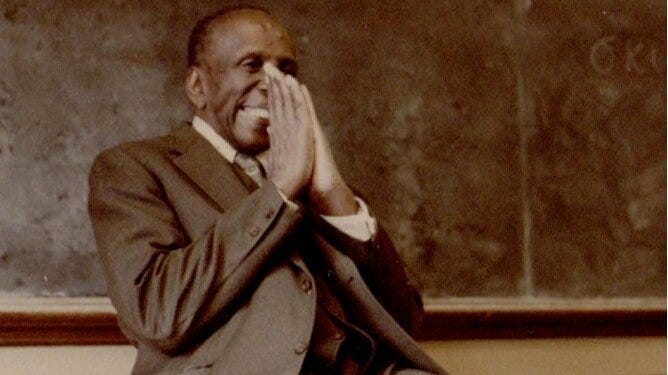

In the 1950s, in a meeting that seems divinely ordered, Howard—now a dean at Boston University—began mentoring a student named Martin Luther King. Howard taught King his love-in-action philosophy, which he first learned from Rufus Jones. Within a few years, King was leading the Montgomery bus boycott. Reportedly, he carried Howard’s book Jesus and the Disinherited in his pocket wherever he went.

Though Howard did not join in direct action during the Civil Rights movement, his stature as one of America’s great spiritual leaders took off. As demands for his time and attention grew, he increasingly sought out solitude for prayer and meditation. Eyes closed, mind quieted, in contemplation’s dark he found union with his Inner Light.

Light that could only be seen by going into the darkness was the recurring motif of Howard’s life. In the prologue for Luminous Darkness, his 1965 book on segregation, he related a story about one of his students who’d spent time deep-sea diving. The student told Thurman about the descent through layers of aquatic life, into a zone where no light penetrates. As the dark deepens, fear and panic grips the diver. But as he goes lower, the diver’s eyes adjust to the dark and he acquires peculiar vision that allows him to see a luminous quality.

The parallels between the diver’s descent, liberation movements and the mystical journey toward God were obvious to Howard. In all cases, darkness—if one can stick it out—eventually reveals a paradoxical light.

The dark was Howard’s ticket to the Light. As a child in the dark he found comfort and the strength to survive and resist segregation. As an adult mystic in the dark he found God. The deep darkness of prayer and meditation allowed him a space to meet God and to meet himself, stripped of all his identities. Spiritually naked, he felt himself washed in the Light, and returned to his true self where all distinctions fell away.

It is my belief that in the Presence of God there is neither male nor female, white nor black, Gentile nor Jew, Protestant nor Catholic, Hindu, Buddhist, nor Muslim, but a human spirit stripped to the literal substance of itself before God.

In prayer and contemplation, Howard heard what he poetically called the sound of the genuine. This was “music” available to anyone willing to practice the spiritual disciplines of opening their heart to the love of God in themselves and others.

In a commencement address delivered at Spelman College in 1980, less than a year before his death, he sketched a vision of radical solidarity built on Jesus’s love-ethic which, he believed, was the only thing that might save the world.

Now if I hear the sound of the genuine in me, and if you hear the sound of the genuine in you, it is possible for me to go down in [my spirit] and come up in [your spirit]. So that when I look at myself through your eyes having made that pilgrimage, I see in me what you see in me. [Then] the wall that separates and divides will disappear, and we will become one because the sound of the genuine makes the same music.

Practice

Nothing comes from nothing, as the saying goes. This is as true of spirituality as anything else. With Rufus Jones and Howard Thurman, you can trace a line from what Rufus absorbed from his Aunt Peace as a boy to how he lived those teachings out, then passed them on to Howard Thurman who, in turn, passed them to Martin Luther King.

Today, think of a spiritual teacher from your own past, someone whose life lessons you carried with you and adapted to your own unique circumstances, and then also passed on. This can be anyone—a parent, grandparent, aunt or uncle, teacher, preacher, coach, etc. Light a candle and then spend five minutes in prayer speaking to them, giving thanks for the gift that they are, or were.

Holidays at Life In The City

All in-person gatherings are at 205 East Monroe Street in Austin, Texas.

Dec. 8, 11:15 am: LITC’s original musical, Make Room In Your Heart. Dec. 21, 6:00 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the longest night of the year. Dec. 23, 6:00 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve service, an LITC tradition! Dec. 29, 11:15 am: Welcome 2025 with a fun, casual service that includes coffee, cookies, conversation and resolution-setting.

Contemplation In The City

Life In The City’s contemplative community meets regularly to practice sacred traditions like Lectio Divina and Centering Prayer. If you’re in Austin, consider joining one of our gatherings. You might also find meaning in our monthly newsletter in which we wrestle with how to live a spiritually engaged life in the modern world. Read more here.

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2022 edition, to find out how my experience of September 11, 2001 became my gateway to Advent.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Catch a typo? Have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets for a future year? Leave feedback in the Comments below or email Greg Durham at greg@litcaustin.org.