The Holy Land is everywhere.

Advent Day 3: Black Elk (c.1863-1950)

In 1872, nine-year old Black Elk fell gravely ill. For twelve days the boy lay comatose in his teepee, on the edge of death. His desperate parents summoned the medicine man, Whirlwind Chaser, to try and save him. What they didn’t know was that, as they prayed and chanted over his lifeless body, Black Elk’s spirit had taken flight into an epic vision.

In this vision, Black Elk was escorted by kind, grandfatherly figures called Thunder Beings. These spirits showed him through a vivid landscape in which signs and images told the future of the Lakota people: they would suffer a great calamity; yet, with Black Elk’s guidance and witness, they would survive and renew themselves.

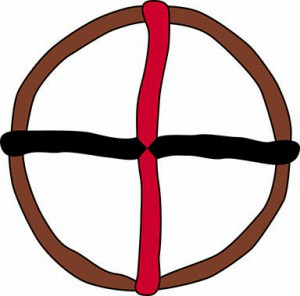

The grandfathers revealed to Black Elk a circle of people representing all humanity. At the center of the circle a tree sprouted at the point where two paths met: a black road and a red road. The grandfathers told Black Elk the black road was one of trouble and war; the red road led to good and peace. They told Black Elk that he would walk both in his life.

The climax—a vision of Lakota restoration, and reconciliation to all humankind—occurred on what is now known as Black Elk Peak in South Dakota:

I was standing on the highest mountain of them all; beneath me was the whole hoop of the world; I was seeing in a sacred manner the shapes of all things as they must live together like one being. I saw that the sacred hoop of my people was one of many hoops that made one circle, wide as daylight and as starlight, and in the center grew one mighty flowering tree to shelter all the children of one mother and one father. And I saw that it was holy.

When Black Elk awakened, his parents, who’d given him up for dead, were stunned. Whirlwind Chaser was credited with the boy’s recovery. But Black Elk knew it was the Thunder Beings who’d saved him…and for a purpose.

But what was that purpose?

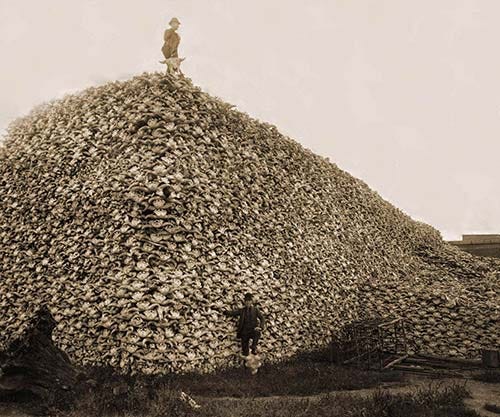

Over the next decade, life as the Plains Indians had long lived it utterly collapsed. While the Lakota, including a teenage Black Elk, defeated Custer at Little Big Horn, they could neither stem the tide of settlers nor silence the guns of government-contracted hunters who drove the buffalo—the Lakota’s lifeblood—to near extinction. By 1880, the Lakota who survived were confined to reservations.

During all this time, Black Elk kept his vision secret. He was afraid to share it not only because its meaning was unclear to him, but also because he feared he hadn’t been granted power through it (in Lakota culture, a vision is prophetic if one receives power—wisdom, healing—by it; if a vision doesn’t bestow power it doesn’t mean it’s not real, only that it has limited value). Another secret: it had not been Black Elk’s first vision. For as long as he could remember he’d had them, and would continue having them throughout his life.

Around 1880, Black Elk finally revealed his vision to a medicine man named Black Road. As Black Elk feared would happen, Black Road commanded him to re-enact the vision for the elders of their tribe through a ceremony called the Horse Dance. They would verify its value.

Black Elk need not have feared. The elders were stunned, and convinced the young man had been sacredly chosen to be a leader and healer—that somehow, someway, Black Elk would not just build a bridge from their proud past through the troubled present and into a brighter future, but that he would actually be that bridge.

Black Elk knew any better future would mean his people taking their place in the wider circle of a universal brotherhood. His vision had told him this. But this was divisive. Many fellow Lakota held to the hope they could still drive out the settlers and army. Black Elk saw this as delusion. Worse, for him, many of his fellow tribesmen were consumed by hatred.

While he easily understood, and lived himself, the pain and injustice that fueled hatred, Black Elk could not find it in himself to hate. No matter how great the tragedy, how plentiful the tears of his people, he saw hatred as a betrayal of his vocation: to walk the good red road through all divides and as a witness of peace for the future.

Peace will come to men when they realize their oneness with the universe. It is everywhere.

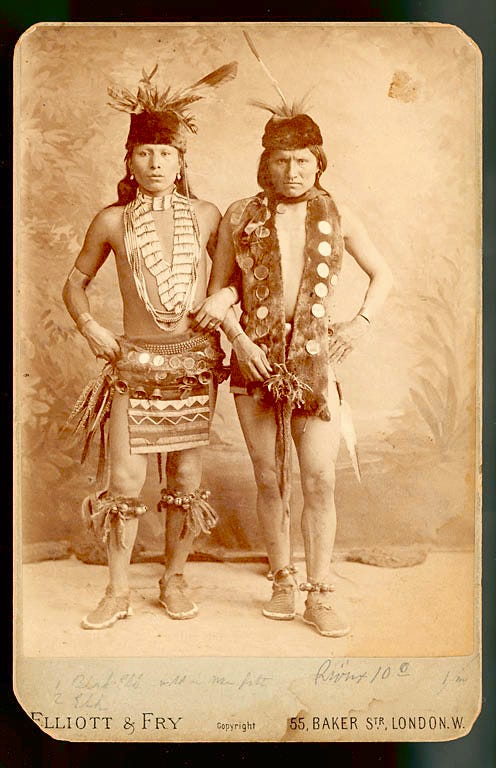

In 1887, needing work, and curious about the world—he was especially excited to see the ocean—Black Elk joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show on a two-year European tour.

The tour left a profound mark on Black Elk. He learned to speak rudimentary English. He was exposed to, and shocked by, the environmental ravages of industrial society. He was briefly arrested as a suspect in the Jack the Ripper murders. Most memorable, however, was meeting Queen Victoria whom he called Grandmother England. When she attended one of his performances, he noted how everyone bowed to her. So, he was stunned when she bowed to him and the other performers. Later, Black Elk was invited to join a private audience celebrating her Golden Jubilee.

Through his travels, Black Elk became more convinced than ever that kindness, concern for fellow humans and love weren’t exclusive to Indians, Europeans, Americans, or anyone. And they weren’t found only in England or South Dakota. This allowed Black Elk to remark with conviction that,

The Holy Land is everywhere.

When Black Elk returned to South Dakota in 1889, things were even worse than when he left. A drought had ruined crops. Even more of the land promised to the Lakota by treaty had been seized. Out of this desperate situation rose a spiritual revival called the Ghost Dance.

The Ghost Dance began among the Paiute of Nevada after a prophet received a vision of a Savior who would come and restore the Native people. Black Elk traveled to Nevada to check it out. After watching the dance, and participating himself, he decided there was good in it, and he brought it back to South Dakota.

Taking part in the apocalyptic, dance-till-you-drop rite, Black Elk received a series of visions in which he once more saw the flowering tree from his childhood vision. Only now, beside the tree was a Christ-like figure who stood with arms outstretched and light pouring through wounds in his hands as he called all people to gather around the tree of Wakan Tanka, the Great Spirit:

Once more I saw the sacred tree all full of leaves and blooming. Against the tree was a man. I looked hard at him and could not tell what people he came from. He was not white and he was not Indian. While I was staring hard at him, his body began to change and became very beautiful with all colors of light and around him there was light. He spoke like singing, “All earthly being and growing things belong to me. Your Father, the Great Spirit, has said this, and you too must say this.”

The popularity of the Ghost Dance alarmed government officials who feared a rebellion was brewing. In December 1890, the Lakota were ordered to give up their weapons. In the process of confiscating them, someone’s rifle discharged. Chaotic shooting broke out, resulting in the deaths of 25 cavalrymen and over 150 Lakota in what is now called the Massacre at Wounded Knee.

At Wounded Knee, the three hundred-year conflict between European-Americans and Native-Americans came to a close. What glimmer of hope had remained for a return to the Lakota glory days was gone.

Around 1892, Black Elk married Katie War Bonnet. The marriage produced three sons and lasted until Katie’s death in 1901. He later married Anna Brings White and had more children. These were joys. But sorrows were plenty. With so many of his people sinking into poverty and despair, Black Elk felt he had failed at his vocation. He hadn’t been able to protect or restore them, and now he couldn’t heal them. This dark cloud of failure only began to lift in 1904 when he met a Jesuit priest.

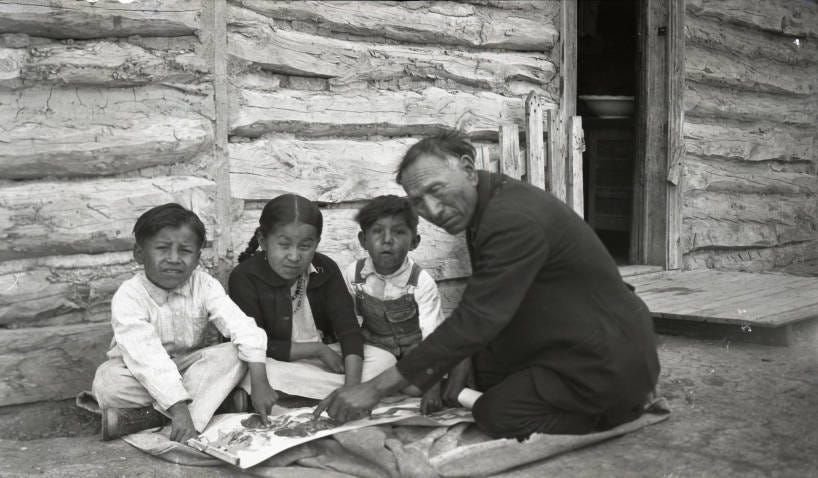

Black Elk had been a lifelong seeker of spiritual wisdom. Yet, he had not been quick to adopt Christianity, or at least the church. But what he heard about Jesus from this Jesuit intrigued him, especially after the priest showed him a pictorial catechism Catholic missionaries used to teach those who couldn’t read or write. This tool depicted two roads, one black, one red, similar to what he’d seen in his childhood vision.

Over the next few years, Black Elk immersed himself in Catholicism. This wasn’t as much of a stretch as one might think. Both Catholicism and the pipe religion of his people reverence ritual and ceremony. Both have a strong focus on communal life and sacrament. In 1907, he became a catechist. In an era where clergy were scarce on the Plains, this meant that, on the reservation, Black Elk functioned as a de facto priest.

For the next four decades, Black Elk served as a spiritual guide to the Pine Ridge reservation. Daily, he traveled long distances in all kinds of weather to offer people prayers and hope and healing, all through his unique Lakota-infused Catholicism. After once believing he’d lost his vocation, now he felt a renewed purpose. His talent for lifting people up and healing their souls was so remarkable that one priest called him a second Saint Paul.

Those of us who are suffering should help one another and have pity.

Not everyone was pleased with Black Elk’s spiritual path. Lakota traditionalists thought he was too Catholic. Catholics thought him too traditional. Black Elk described himself as a man of two minds. But these minds weren’t at war. Rather, they talked to, informed and elevated one another. He was just as comfortable praying with his sacred pipe as he was his rosary. He was as at home in a church as in a sweat lodge. Being Christian wasn’t a break with his past; it was just another source of wisdom he integrated into his long, seeker’s life.

In the mid-1930s, Black Elk was visited by a poet from Nebraska named John Neihardt. The interviews Black Elk gave Niehardt form the basis of the book Black Elk Speaks. When it was released in 1934, not many people bought it. But in the years since it has risen to become the most popular book ever released about a Native American figure. While modern scholarship has corrected Neihardt’s misinterpretations of Black Elk’s words, what Niehardt got right—and what remains intact—is Black Elk’s unitive vision of peace, which is apparent in this prayer he shared with the author:

Great Spirit, behold me on earth and lean to hear my feeble voice. You lived first, and you are older than all need, older than all prayer. All things belong to you—the two-leggeds, the four-leggeds, the wings of the air and all green things that live. You have set the powers of the four quarters to cross each other. The good road and the road of difficulties you have made to cross; and where they cross, the place is holy. Day in and day out, forever, you are the life of things. Therefore I am sending a voice, Great Spirit, my Grandfather, forgetting nothing you have made, the stars of the universe and the grasses of the earth.

To the end, Black Elk refused to let others define him or box him in. He was the gathering together of all he’d seen and lived through, and all that found a home in his heart: Lakota and American, Catholic and medicine man. Deeper still, he believed that he, and all of creation, was beyond distinction, and one with the Creator. For Black Elk, this was his power and peace:

…peace comes within the souls of people when they realize their relationship, their oneness with the universe and all its powers, and when they realize at the center of the universe dwells the Great Spirit, and that its center is really everywhere, it is within each of us.

Black Elk died on August 19, 1950. As he lay on his deathbed, he told his daughter Lucy that, once he passed, if everything was okay with him on the other side, she would see a sign. The next evening during his wake, the northern lights flared over Pine Ridge.

In his lifetime, Black Elk saw epic changes no one alive today can fathom. In the last glory days of the Lakota, he had a boyhood vision of both calamity and a universal brotherhood that lay beyond that calamity. This vision shaped his entire life, and sustained him through the cataclysmic events that destroyed so many others. Out of that destruction—improbably, mysteriously—rose a legacy of love: love for his people and all people who share this one planet we call home. He summed up these values in the closing lines of a letter he wrote in 1907:

There is one important law…to love one another, and be thankful for each other. We are all related.

Practice

Black Elk recorded that in his first vision, at age five, he heard a song being sung to him:

Behold! A sacred voice is calling you. All over the sky, a sacred voice is calling.

Listening for that sacred voice, and heeding its call to be a blessing to everyone he met, was the foundation of Black Elk’s spirituality. Today, set aside time to listen for the sacred voice calling you. To get yourself into a receptive state so you may better hear that voice, try this beautiful 5-minute meditation from Brother David Steindl-Rast.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

Dec 10, 11:15 am: LITC’s original holiday musical, Make Room In Your Heart.

Dec 21, 7 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the darkest night of the year.

Dec 23, 6 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve, an annual LITC tradition

Dec 24, 11:15 am: LITC’s regular Sunday service

Dec 31, 11:15 am: A fun, casual service with cookies and coffee to welcome 2024

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2023 edition of The Heart Moves Toward Light: Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Did you catch a typo? Do you have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets we might cover in the future? Leave feedback in comments section below or email Greg Durham at greg@lifeinthecityaustin.org.

I’m embarrassed to say I know nothing about Black Elk. What a great introduction, and, like all your pieces, sparks me to want to learn more. Thanks friend for this beautiful and disciplined practice you offer us. ❤️🙏🏼

Wonderful as usual!

I noticed one typo beneath the picture of Black Elk teaching the children. The title of the book “Black Elk Speaks” is only partly italicized.