There is no pit so deep that God's love is not deeper still.

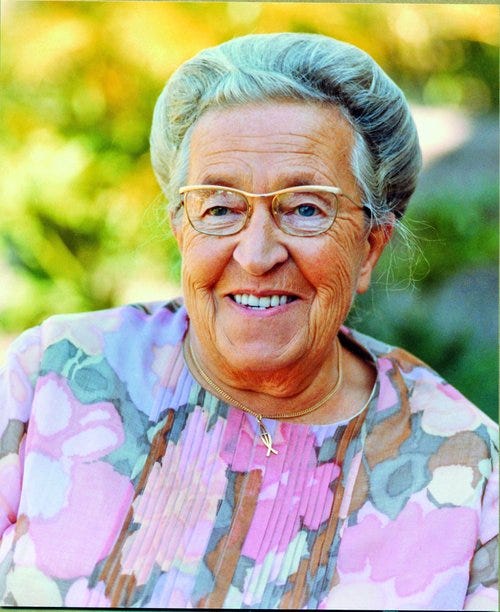

Advent Day 7: Corrie Ten Boom (1892-1983)

The morning of February 28, 1944 dawned cold and dreary in the Dutch city of Haarlem. Corrie Ten Boom was bed-ridden with the flu when her sister Betsie came in and said there was a man waiting to see her. Who? Corrie asked. Betsie didn’t know. She’d never met him before.

Corrie’s head pounded with fever. She wanted only to sleep. But the visitor was insistent, Betsie said. Corrie sighed, tossed off the covers and descended the stairs to her watch repair shop on the first floor.

The man waiting for her was small, pale and sandy-haired. Standing there, hat in hand, rain dripping off his shoulders, he looked scared, like the hundreds of others who’d come to her in the four years since the Nazis had invaded.

“Is this about a watch?” Corrie said.

“No,” the man said. “Something far more serious.”

His family had been hiding Jews. Now his wife had been arrested. He needed 600 guilders. With that, he could bribe a policeman and gain her release. He had heard Corrie had helped so many others, in secret. Could she now help him?

“Please,” the man begged. “It’s a matter of life and death.”

Corrie looked the stranger over. She was unsure whether to trust him. She had no reason to. Nor did she have a reason not to. But she had been risking her life every day for four years to help people like this. How could she stop now?

“Come back later,” Corrie said. “I’ll get the money for you.”

Everything the man said had been a lie.

Not long after he left, Corrie was back in bed. She had just dozed off when the bell she’d installed in the house to warn of impending danger rang. Suddenly, the half-dozen refugees she’d been sheltering—Jews and resistance workers—flew into her room and dove through the open false wall at the back of her linen closet, into the crawl space they called the Angel’s Den. Only seconds after the last one was in and the wall set in place, the Gestapo burst through the door.

Corrie Ten Boom was the youngest of four children born to Cornelia and Casper Ten Boom. The family home on the corner of a commercial street in Haarlem had been inhabited by Ten Booms for generations. This crowded space included a rotating cast of extended family, foster kids, friends and neighbors. Years later, those who’d had the good fortune to know the Ten Booms remembered their home as a hub of laughter, generosity and music.

The pillars of Ten Boom family life were love, service and compassion, guided by the gospel command to love one’s neighbor as oneself. The meaning of life, Corrie and her siblings were taught, was not its duration but its donation. Until her death in 1921, Corrie’s mother, Cornelia, ran the house as an unofficial charity. A visitor on any given day was likely to cross paths with both neighbors in need and neighbors Cornelia had cajoled into offering money and goods. As for Casper, he often refused payment for watch repair if he knew a customer was having a tough time. Once Corrie was grown and in charge of the business—as the first certified female watchmaker in Holland—she upheld this tradition.

This ethic of devotion to neighbor took on a whole new urgency and risk after the Nazis invaded Holland in 1940. As persecutions mounted, the Ten Booms went into action. They offered aid to those whose homes and businesses had been attacked. They stored items of value to individuals and the community, including the book collection of Haarlem’s rabbi. They cooked up a crazy, and ultimately successful, scheme to rescue Jewish children from the local orphanage. They organized passage to safe houses that Corrie’s brother, Willem, had arranged. So, it was only a matter of time until the Ten Boom house itself became a sanctuary.

This happened one night in May 1942 when a woman named Mrs. Kleermaker appeared at their door. Her husband had been arrested. Her son had gone into hiding. She was afraid to go home. She knew of their reputation for kindness. Could they help?

Corrie welcomed Mrs. Kleermaker in. She, her sister Betsie and their father fed the woman and gave her a bedroom upstairs. Two nights later, there was another knock. This time it was a couple. Like Mrs. Kleermaker, they were afraid to go home. Though sheltering them was a crime, Corrie opened the door and let them pass.

From then on, there was no turning back. The Ten Boom house, which over the decades had been the scene of so much generosity, now became a shelter of love and sanity in a world gone mad. Though Corrie often found herself gripped by fear, she clung to her new mantra:

Never be afraid to trust an unknown future to a known God.

By the time the sandy-haired man appeared in Corrie’s shop on February 28, 1944, Corrie and her family had sheltered and arranged the escape of more than 800 Jews.

The Gestapo interrogated the Ten Booms for hours. Where were they hiding Jews? Corrie, Betsie and Casper denied hiding anyone. The Gestapo looted the house, tearing open drawers and cupboards. They turned up the ration cards Corrie had secretly obtained to feed their refugees, as well as Dutch Underground fliers. This was all they needed to prove guilt. Still, they were determined to find the hiding spot.

They insulted and punched Corrie, Betsie and Casper. Through it all the Ten Booms never broke. As she wiped blood from her mouth, Betsie—whose extraordinary capacity for forgiveness had always been both inspiration and frustration to Corrie—even said she felt sorry for the officer who abused her.

Miraculously, the police never found the hiding spot. After nightfall, they finally gave up. They then arrested the Ten Booms and marched them, along with dozens of others who’d shown up at the home looking for help over the previous hours, to jail.

In jail they were separated, Betsie taken one way, Casper another, and the ringleader Corrie to solitary confinement. The next day, Casper was offered the chance to leave due to his frail health, but he informed the police that if they released him he would only resume helping people. The police held him. He died in custody a week later.

After three months, Corrie and Betsie were reunited, only to be transferred, first to a prison camp in Holland, then aboard a crammed cattle car to Ravensbruck, a concentration camp deep in Germany.

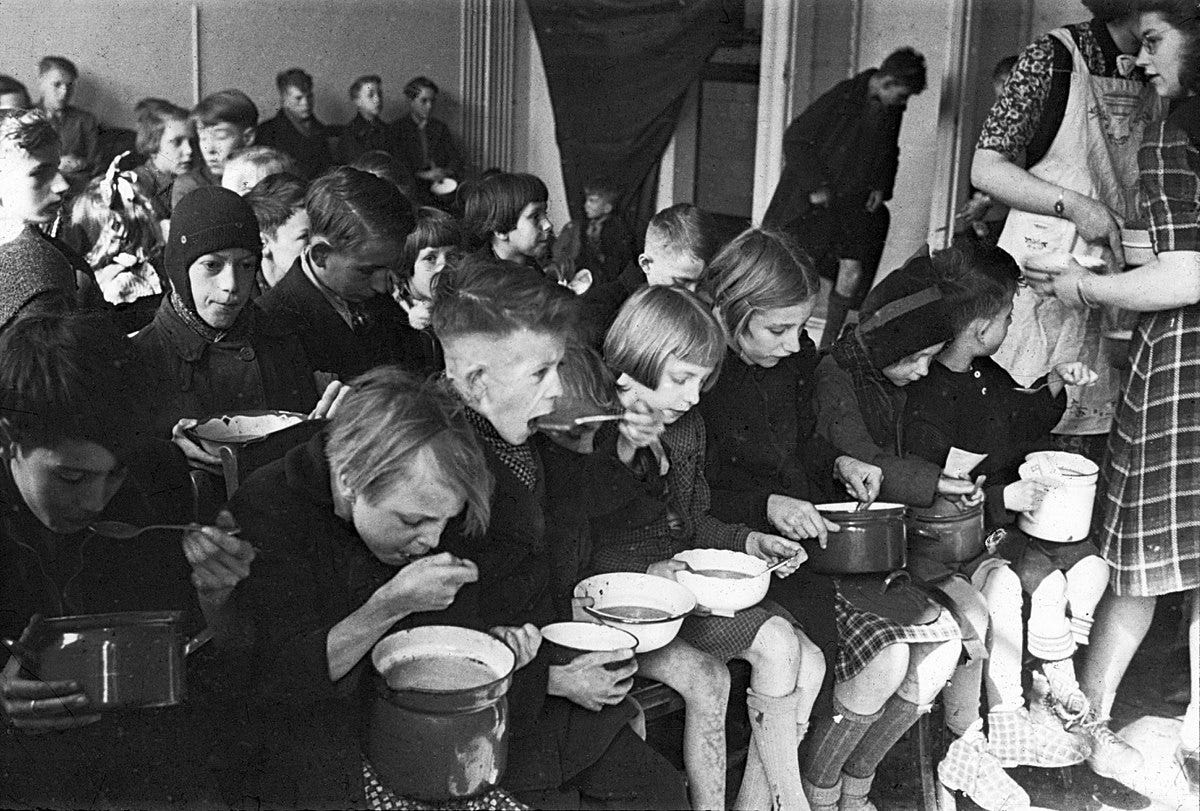

Life at Ravensbruck, like all such places, was brutal. Food was scarce. Shelter was 700 to a flea-infested barracks built for 50. Sickness and starvation were rampant. Prisoners were no longer individuals with dignity and names but numbers. Betsie became #66729, Corrie #66730.

The Ten Boom’s faith, which had always formed the core of their identity, was now, for Corrie and Betsie, a life raft, with Corrie remarking,

You can never learn that Christ is all you need, until Christ is all you have.

Under the most extreme circumstances, Corrie and Betsie continued their ministry of love and hope in Ravensbruck. They held secret prayer services in their barracks. They started a kind of mutual support group they called the Encouragement Society. They shared what little food and medicine they had with those suffering even more than them.

The latter came at great cost, especially to Betsie who had never enjoyed robust health. Over their first months in the camp, she deteriorated quickly. Her spirit, however, remained strong, as did her faith in God and people.

One night, as they were made to stand at attention in the cold for hours—one of the camp guards’ many pointless punishments—Betsie whispered to Corrie,

If people can be taught to hate, they can be taught to love. We must find the way, you and I, no matter how long it takes.

For a moment, Corrie thought her sister was speaking of their fellow inmates, many whom had been transformed by hunger and rage into pitiful, and pitiless, creatures. When she realized Betsie was speaking of their captors, she was stunned.

In the weeks ahead, even as her body faded, Betsie’s spirit bloomed. More and more she talked to Corrie about what their lives would be like once they were released, and how they would help heal the world. She was having dreams and visions of a big house back in Holland which they would fill with people like them who’d lived through the concentration camps.

It’s such a beautiful house, Corrie! The floors are all inlaid wood, with statues set in the walls and a broad staircase sweeping down. And gardens! Gardens all around it where they can plant flowers. It will do them such good, Corrie, to care for flowers!

In December, Betsie’s health took a turn for the worst. One night, she seemed to be hallucinating. Like before, she began to speak of a place where they would run a ministry of healing and forgiveness once the war was over. They would paint it in bright colors and plant flowers. But instead of this place being for former prisoners, it would be for their captors.

The Germans are the most wounded of all the people in the world. It will be so good for them. . .watching things grow. People can learn to love from flowers. . . .

The next day, Betsie was unable to get out of bed. Orderlies came to the barracks to take her away. As they crossed the camp grounds, Corrie walked alongside the stretcher. Betsie started talking again. Corrie leaned close to hear.

We must tell people what we have learned here. We must tell them that there is no pit so deep that God is not deeper still. They will listen to us, Corrie, because we have been here.

These were Betsie’s last words. She died that night.

Two mornings later, Corrie was standing in the cold during the daily roll call when a voice over the camp loudspeaker summoned her to the administrative building. When she arrived, she asked another woman who’d also been called why they were there. “Death sentence,” the woman said matter-of-factly.

Corrie was made to wait for hours. During this time, she prayed that however they were going to kill her, it would be fast. Finally, it was her turn to see the administrator. But instead of a death sentence she was handed a release form and a pass granting train passage to Holland. She was then pointed to a room where she could trade her camp garb for a dress.

Just like that, and with no idea why, Corrie Ten Boom was free. Later, she would learn it was a simple clerical error. But by then, she was gone. Ten days later, all the women in her age group at Ravensbruck were murdered.

Post-war Holland was a landscape of famine, revenge and recrimination. After the Nazi defeat, the tables turned on those who’d collaborated with them. Back in Haarlem, Corrie saw people she’d once known shunned and shamed, fired from jobs, homes taken from them. Many were arrested. Many just wandered the streets, heads shaved and bodies bruised by mobs set on vengeance.

Despite her grief and the heavy toll of the war on her family (in addition to losing her father and sister, her nephew Kik had disappeared and her brother Willem would soon die), Corrie wasted no time starting the ministry of healing and reconciliation that Betsie had envisioned. Wherever and whenever she could—in churches, to civic groups, on street corners, and to anyone who would listen—she spoke of the need to heal and forgive in order for the world to recover.

One day, after one of these talks, an elderly woman approached her. She had nearby a 56-room mansion. Could Corrie think of anything to do with it that would help in the healing of the world?

Corrie went for a look. It was just as Betsie had described from her vision: inlaid floors, a broad staircase, flower gardens. Yes, Corrie said, she could use it.

She soon accepted the first residents. Many had been in concentration camps. Others had hidden in attics and crawl spaces for years. All were damaged. All were in desperate need of physical, mental and spiritual rehabilitation.

From the first, Corrie believed that forgiveness was the key to full rehabilitation. As such, she experimented with inviting those who’d collaborated with the Nazis to live at the home. But for the residents who had suffered so much, it was too much, too soon. So instead, Corrie turned her own home into a rehabilitation center for the collaborators who she knew needed just as much—and in some ways more—healing than those held captive.

This was the beginning of a ministry she would carry on nearly to her dying day. And nowhere was her work more needed, nowhere did it ask more from her, than Germany, a place she returned to only a year after the war’s conclusion.

In one particularly poignant scene in Munich, a guard who remembered her from Ravensbruck approached after a talk in a church and asked for forgiveness. Face to face with one of her captors, Corrie felt nothing but contempt. Angry, vengeful thoughts coursed through her. She prayed to God to help her but she felt not the slightest spark of warmth or charity. Then, before she even realized what she was doing, she reached out and took the man’s hand. Suddenly,

…the most incredible thing happened. From my shoulder along my arm and through my hand, a current seemed to pass from me to him, while into my heart sprang a love for this stranger that almost overwhelmed me. And so I discovered that it is not on our forgiveness any more than our goodness that the world’s healing hinges, but on God’s…Forgiveness is an act of the will, and the will can function regardless of the temperature of the heart.

In 1947, an opportunity arose to create a center for rehabilitation and reconciliation at a former concentration camp in Darmstadt. When Corrie toured it for the first time, walking among the gray barracks and barbed wire, she remembered Betsie’s vision of ugliness transformed into beauty, and hate transformed to love. She turned to her guide and said,

Windowboxes. We’ll have them at every window. The barbed wire must come down, of course, and then we’ll need paint. Green paint. Bright yellow-green, the color of things coming up new in the spring. . . .

Over the next three decades, Corrie Ten Boom carried her ministry of love, mercy and forgiveness around the globe. By the time a stroke forced her to stop traveling in the late 1970s, she had gone into more than sixty countries, many of them dangerous, desperate, and shattered by war and hatred. In each one she offered herself as a witness for healing, and the impossible becoming possible.

According to ancient Jewish tradition, dying on your birthday is a blessing bestowed only on those who’ve fully completed their life’s mission. And so fittingly, Corrie Ten Boom died on April 15, 1983, her ninety-first birthday.

Practice

Today’s practice is simple yet very challenging. Ask your self two questions:

What do I need to forgive?

Of what would I like to be forgiven?

Work with the answers however feels right for you today: during a walk, by journaling, in prayer and meditation, etc.

Holidays at Life In The City

All in person events take place at 205 East Monroe Street in Austin, Texas.

Dec. 8, 11:15 am: LITC’s original musical, Make Room In Your Heart.

Dec. 21, 6:00 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate gathering on the longest night.

Dec. 23, 6:00 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve, an LITC tradition!

Dec. 29, 11:15 am: Welcome 2025 with a fun, casual service that includes cookies, coffee and resolution-making. Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2022 edition, to find out how my experience of September 11, 2001 became my gateway to Advent.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Catch a typo? Have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets for a future year? Leave feedback in the Comments below or email Greg Durham at greg@litcaustin.org.

I have been inspired by Corrie and her many spiritual lessons since reading A Hiding Place in my early twenties. Thank you for reminding me of even more!