I am comforted by the knowledge that God is always with me.

Advent Day 8: Margery Kempe (1373-c.1438)

Did you ever take your dream trip only to have it plunge into disaster? That’s exactly what happened to Margery Kempe. The year was 1413, and she was on the journey of a lifetime: a two-year pilgrimage to Jerusalem. But as soon as she left her native England, she wasted no time alienating her travel buddies with her eccentric habits—wearing only virginal white despite being married with fourteen children; chattering about God from sunup to sundown; and breaking into frequent fits of sobbing from both joy and sorrow.

By the time the party reached Venice, the other pilgrims were done. They stole her money. They lured her servant into abandoning her. They raided her suitcase and left behind only a sackcloth for her to wear. They refused to share meals.

Margery took it all in stride. What were her trials compared to those of Jesus? What was losing a servant compared to being betrayed by Judas? What was being forced to wear a burlap skirt compared to a crown of thorns? Nothing.

Besides, it was the well-off pilgrims—for whom Christianity was more social than soulful—who shunned her. Among the poorer pilgrims who lived outside the bounds of polite society and who loved God as fervently as she did, Margery was a kind of folk heroine.

Margery hadn’t always been so Spirit-filled. Born in 1373 to a fairly well-off merchant family in King’s Lynn, England, she was, by her own admission, proud and vain. Then, at twenty, after birthing her first child, she had a psychotic break. She began to curse her husband. She thrashed and screamed. She bit herself with such ferocity it left permanent scars on her arms. Worst of all, she had visions in which demons convinced her to renounce God.

Then, one morning, after six months of this psychological and spiritual torture, she had a startling vision: Jesus walked into her room, sat on the edge of her bed and asked, “Daughter, why have you abandoned me when I never abandoned you?” Before she could answer, Jesus disappeared. She soon made a swift recovery, and was back to being the old Margery.

This wasn’t entirely a good thing. Now her psychosis was gone, it was replaced by something nearly as insidious: spiritual pride. Having been “visited” by Jesus, Margery viewed herself as something of a super-Christian, loudly proclaiming to anyone who would listen that everything she did, from brewing beer to milling flour (Margery was a serial entrepreneur), was for the glory of God. Really though, it was for the glory of herself, and to buy fancy clothes and goods…anything that would gain her the admiration and envy of others:

My neighbors were very jealous of me, and wished that they were as well-dressed as I was. My only wish was to be admired. I never thought I was wrong, and unlike my husband I wasn't content with the things God gave me; I always wanted more than I had.

Margery awoke from her delusion of spiritual superiority one morning when she heard the sounds of sweet music and was washed in a warm glow and the sudden awareness that she was secure in God’s love and grace and always had been, and there was nothing and no one that could ever separate her from God. Her life would never be the same.

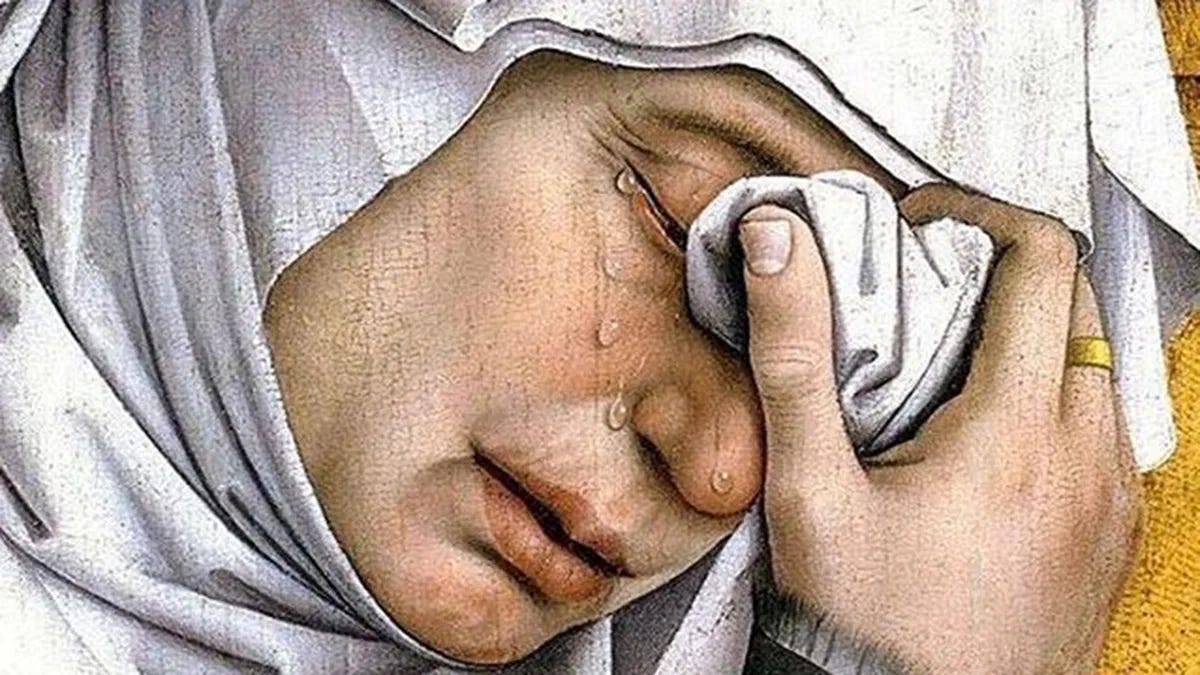

Now Margery really did center God in her life. And she lived this out loud…really loud. Everyone’s spiritual devotion finds its natural expression, and for Margery it was tears. After her conversion experience, she found herself overcome by frequent fits of sobbing. She sobbed tears of joy for the gift of God’s love. She sobbed tears of sorrow for Christ on the cross. She sobbed at home, in the street, at church, in the market.

Like many mystics of the Middle Ages she also took up acts of penance to share in the sufferings of Christ. She began to wear a hair shirt like the one pictured below. She went in for extreme fasting. And she resolved to live a chaste life, not because she wasn’t into her husband anymore but because she was too into him (as evidenced by their fourteen kids).

This last bit was complicated because it required her husband’s sign-off. For a long time, John Kempe was not okay with this. He thought it was a phase, it would pass. But then it didn’t. Finally, one day, they were walking together and this happened:

John: Margery, if a man came along with a sword and threatened to behead me unless you slept with me, what would you do?

Margery: Let him kill you, of course.

John was not amused. Grumbling that she was no longer “a good wife”, he released Margery from her marital duties.

Margery wasn’t single long though. Soon after, she had a vision in which she married Jesus (bridal mysticism was common in the Middle Ages). After, she placed a wedding band on her finger and would only wear white, signifying her “virginity”.

Even in a time when extravagant displays of religious feeling were not uncommon, Margery’s Olympic-level devotion was notable. She attended every single church service in her town. She took daily communion and made confession three times a day. And always there was the crying.

Then there were her travels. Relieved of wifely duties, she was free to roam, and she did, canvassing England to meet with bishops and priests, visiting saints’ relics, engaging in God-talk with anyone willing to chat. More than anything, Margery wanted to share the love of God with people, and let them know they could transform their lives like she had.

Unsurprisingly, Margery had her fair share of haters. The mildest of them saw her as a faker seeking attention. The worst, and most dangerous, were those who believed her a heretic.

In the years to come, Margery would often be accused of heresy. Never mind she never said anything remotely heretical. In fact, she was wildly, annoyingly orthodox which is why, despite numerous interrogations and inquests, she was never actually found guilty. Rather, she was always released with a warning to stop acting the way she did. But if you think she heeded that advice, you don’t know Margery!

Margery Kempe was simply unlike any woman anyone had ever met. She was so raw, so unselfconscious, so…free! When she was happy she showed it. When she was sad she showed it. She was utterly herself. This threatened not just religious sensibilities but the social order. And therein lay the true heart of the objections to Margery. The Mayor of Leicester acknowledged as much when he arrested her, saying she was a bad example for the town’s wives who might also be inspired to leave their husbands, “marry” Jesus and hit the road.

And yet, as many haters as Margery had, she had fans in equal measure. This was especially true among women and the poor who fed and sheltered her during her travels, and who admired her courage in disregarding social norms to share her love of God, like when she preached on street corners, something forbidden by law (resulting in more accusations of heresy).

Confident as Margery was, you can only be called crazy so many times until you start to wonder if it might be true. In 1413, Margery decided to get a second opinion on her sanity, and she went straight to the top: famed mystic Julian of Norwich.

Over several days, these two women who are now considered the greatest mystics of the English Middle Ages sat together. Margery poured out her heart and Julian listened. Then Julian gave Margery a simple formula for knowing if what she was experiencing was truly of God: God was love, Julian said; therefore, God would never lead Margery to think, act or do anything that wasn’t rooted in love. So, did her visions and experiences lead her to ever more love and compassion? Was she motivated by a pure desire to share God’s mercy and grace? Yes and yes, Margery answered. Satisfied, Julian assured her she was the real deal.

With Julian’s endorsement, Margery entered a bold new stage. In 1413 she left England for the first time and embarked on an epic two-year pilgrimage to the Holy Land. In 1417 she journeyed to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. In the 1420s she crisscrossed England, continuing to meet opposition and charges of heresy. Significantly, she was never convicted. Though there would always remain those who would like to see her go to sea in a bottomless boat, more and more she earned grudging respect even from those who found her intolerable.

Through it all, Jesus remained at the center of Margery’s life. Her devotion never mellowed. Once, when a priest saw her weeping and told her she needed to calm down because Jesus had been dead a long time, she replied:

Sir, his death is as fresh to me as if he had died this same day, and so, I think, it ought to be to you and to all Christian people. We ought always to remember his kindness, and always think of the doleful death that he died for us.

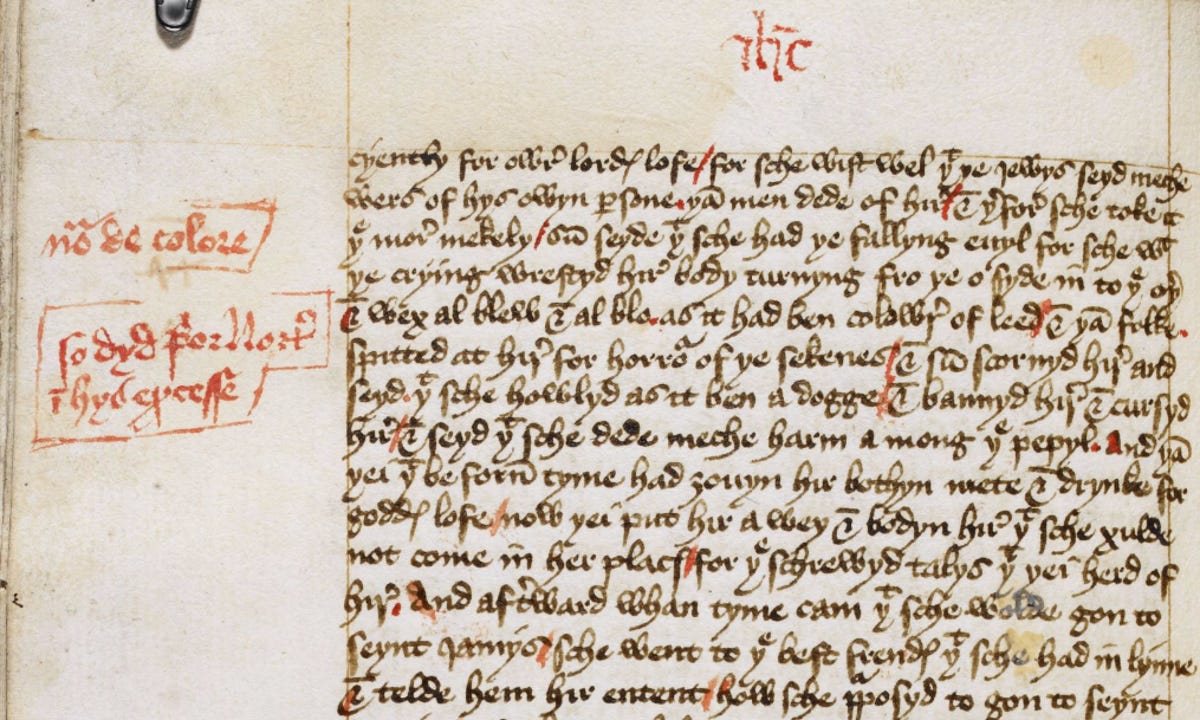

In the 1430s, when she was in her sixties—old by 15th century standards—she made a move that would greatly please future historians: she committed her life story to paper.

The Book Of Margery Kempe is the oldest surviving memoir in the English language (fun fact: Margery’s friend Julian of Norwich’s Revelations Of Divine Love, written two decades earlier, are the oldest English-language writings by a woman). Not only is it a remarkable recounting of one extraordinary woman’s spiritual journey, it offers a unique window into daily life during the late Middle Ages.

While The Book of Margery Kempe was well-known in its time, by the 16th century it had disappeared only to re-emerge in 1934 when a guest at the home of Lieutenant Colonel William Butler-Bowdon went rummaging through a cupboard looking for a ping-pong ball and instead found the only surviving manuscript. Since then it has joined the canon of great mystical texts.

In 1430, after decades spent ranging Europe and the Near East, Margery finally came home to King’s Lynn. Her long-suffering husband John had been left paralyzed by a fall and needed care. After the freedom he’d given her to live her best life, she felt she owed him the honor of caring for him as he neared the end of his. Margery couldn’t help but note how her life with John had come full circle: the body she had once so loved, then later left for God, God re-called her to care for in the end.

In 1438, Margery is listed as being inducted into the Trinity Guild of King’s Lynn. It is the last we hear of her. After this, she disappears into the mists of time. But her legacy endures, of a spiritual giant who was not a hermit out on a heath, or a nun locked away in a convent, but an everyday woman who relinquished the comforts of her life, who emptied herself of pride and vanity and all desire for public approval, to live an authentic spiritual life, in her own way, on her own terms, and true to her own heart.

Practice

Today is Sunday. Rest, replenish and renew, however that looks for you. See you back here tomorrow.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

Dec 10, 11:15 am: LITC’s original holiday musical, Make Room In Your Heart.

Dec 21, 7 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the darkest night of the year.

Dec 23, 6 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve, an annual LITC tradition

Dec 24, 11:15 am: LITC’s regular Sunday service

Dec 31, 11:15 am: A fun, casual service with cookies and coffee to welcome 2024

Feedback

Did you catch a typo? Do you have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets we might cover in the future? Leave feedback in comments section below or email Greg Durham at greg@lifeinthecityaustin.org.

WOW! I'd heard her name, but I never knew about Margery Kempe. What an extraordinary life. And Julian gave Margery great spiritual direction, which caught my attention because I'm a professional spiritual director. I feel like I've had a continuing education course in this one post. Thank you!