What was just a person is now a holiday without limits.

Advent Day 8: Rumi (1207-1272) and Shams (1185-1247)

According to legend, one of history’s most auspicious spiritual friendships began in a most inauspicious manner. It was November 15, 1244, and a young man wearing the cloak and turban of a religious scholar was reading by a lake in the Turkish city of Konya when an old man in tattered clothing passed by.

“What are you doing?” the curious old man asked.

From his ragged appearance, the young man took him for an uneducated beggar. “Something you wouldn’t understand,” he replied.

The old man snatched the book from his hand and tossed it in the water.

The younger man jumped up. “What are you doing?” he shouted.

“Something you wouldn’t understand,” the old man said.

On paper they could not have been more different. The younger of the two, Rumi, was a thirty-seven year old husband and father. His home was cosmopolitan Konya with its multicultural mix of Muslims, Jews, Greeks and Christians (fun fact: the apostle Paul visited during his travels centuries earlier). There, he was a highly-regarded preacher, teacher and member of the “turbaned class” who held posts at multiple colleges.

Shams, on the other hand, was a nearly sixty-year old eccentric Sufi mystic originally from Tabrizi, in modern day Iran. He had little formal education, and had spent his life wandering around Persia, studying with spiritual masters, surviving on the little he made as a basket-weaver. More than anything, he burned for the love of a God he called Love.

Though their initial encounter was tense, it proved to be electric for both men. According to Rumi’s son, on meeting Shams the veil fell from my father’s eyes. Before long, they had moved from arguing next to the lake to all-night conversations to plotting their retreat from the world. Before the end of 1244, Rumi announced to his surprised family and friends that he was going off for a while with Shams to live in a fishing village. Thus began, for Rumi, the initial intense burst of what would become a lifetime of ongoing spiritual transformation.

The retreat from city life could not have been better-timed for Rumi. Whereas once he had taken pride in the respect bestowed on him by his social and professional position, by the time he met Shams he felt only a peculiar emptiness that accolades failed to fill. The self-centeredness his life stirred in him had begun to feel like a heavy burden.

For some time, like everyone, I adored myself. Blind to others, I kept hearing my own name.

More than just a great spiritual master from whom he hoped to learn, Rumi saw Shams as his liberator.

As for Shams, he felt he had finally been gifted the disciple he had desired—someone who also longed for a life of mystical union with God.

Rumi had been mystically inclined since his childhood in Balkh, in modern-day Afghanistan. As a boy, his soul burned for God and he felt the presence of angels. But as he grew up, as is so often the case, his sharp spiritual instincts were dulled by the religious institutions and social conventions of his time. He sought God less in the free and fertile landscape of his soul and more in books, education and creeds. By the time he met Shams he had traded a wild, mysterious God for one who was tame and controllable.

Shams spent the first nine months of their friendship reigniting the original fire of Rumi’s faith. He taught his student how to locate his Inner Light through prayer and meditation. His instruction to Rumi was to simply live life: You want to know about the moon? Go up on the roof at night and look. You want to know about the lake? Taste its waters. You want to know about fire? Feel its heat. Like this, you will come to know God because everything—all creation and every experience—is a gateway to the Eternal.

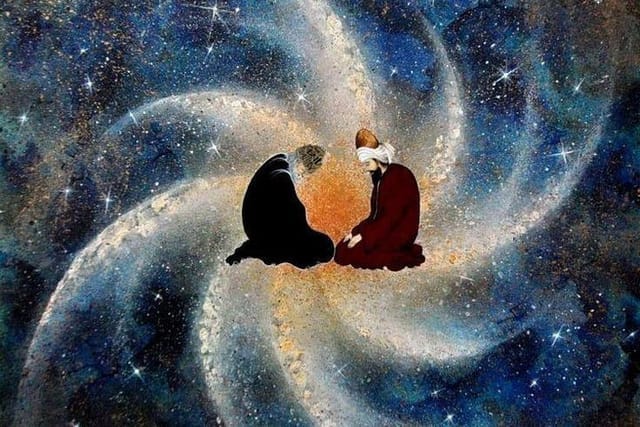

But of all the gateways to God that Shams opened for him, none led Rumi into deeper territory than their friendship which proved to be the liberation he was hoping for.

When Shams shone his light from nowhere, I felt a holiday without limits begin where once was just a person.

In this initial intense period, Shams peeled back Rumi’s layers. He pushed him to discard the logic and pretty words Rumi had mastered in his education and career. These, Shams said, were veils hiding the truth. Whatever ideas or beliefs on God Rumi had that came from others, he urged Rumi to abandon them. All knowing about God needed to come from deep within. So, out was memorized scripture, learned commentary and creedal statements. In was poetry, music and dance, especially sama, Sufism’s meditative form of body prayer.

Of this time of radical transformation, Rumi would later say,

When [Sham’s] love enflamed my heart, all I had was burned to ashes, except…love. I put logic and learning and books on the shelf.

The faith that Shams initiated Rumi into held love as its center—love as a way of life, as a way of seeing, and as the path to a God who is Love.

Wherever you are, and whatever you do, be in love. Love is the bridge between you and everything. Love doesn't need any name, category or definition. Love is a world itself…the water of life. Drink it down with heart and soul.

Re-centering his life in this way was not easy, for it demanded of Rumi that he die to anything less than Love—as Jesus once told Nicodemus he must also do—in order that he might be born again. This meant trading, once and for all, his sterile, head-centered knowing about God in exchange for a fertile, heart-centered unknowing. In its early stages, this process often felt like actual death, leading Rumi to observe,

The way of love is not a subtle argument. The door there is devastation.

Anyone who has been undone by love, forced into change, or brought low on the path toward a higher calling, knows what Rumi is talking about here.

Though their initial roles were guru and disciple, as winter 1245 bloomed into spring then greened into summer, the lines began to blur. As is always the case in loving, healing relationships, Shams began to see that he was as much Rumi’s student as Rumi was his.

But it is Rumi who left behind the voluminous written record about their friendship. And in that record, he calls Shams—which means sun in Arabic—his source of light, the morning wind, Jesus’ healing breath, birdsong…Shams is all of these and a guide, the hand that never pulls away.

In fall 1245, Rumi finally returned to Konya, with Shams in tow. His transformation from a rule-based religious scholar to a free-spirited love mystic was a source of curiosity and confusion among his students and not a little consternation among the conservative religious establishment. Now, wherever Rumi went, there was Shams. While, in theory, Rumi had resumed his official duties, in fact it was often his older friend who did the teaching and preaching while Rumi sat quietly by.

Whereas in the pre-Shams days when Rumi’s students sought to know God he would prescribe Quran memorization or studying one of the great Islamic commentaries, now he told them,

If you want to live your heart and soul, find a friend like Shams and stay near.

In their free time, and in defiance of the segregation of their time and place, Rumi and Shams explored the Jewish markets, visited Christian churches, relaxed in Turkish steam baths, and talked Plato with Greek merchants. This impious eccentricity was tolerated due to Rumi’s prestige, yet jealous gossip raged. Describing this time years later, Rumi’s son wrote that people accused Shams of “hiding [Rumi] away from everybody else so we no longer may see his face or sit at his side.” Worst of all, it was said that “[Shams] must be a magician casting an evil spell...”

For Shams, the whispers became too much to bear, and carried with them a strong scent of danger. In 1246, he left Konya, only to change course and come back a few months later, to then leave again in 1247, without telling Rumi. And this time he was gone for good.

Distraught, Rumi searched the city in their old familiar haunts. With Shams nowhere to be found, he fell apart. He wailed and moaned. According to Rumi’s son, His voice and his cry reached the sky. Everyone heard his lamentations. Then he entered a trancelike sama dance, only now he gave it his own unique spin…literally. For two days he turned round and round until finally he collapsed. This dance eventually inspired the creation of the Sufi order of whirling dervishes, which was started by Rumi’s son in 1273.

Over the next couple years, Rumi undertook several extended journeys across the Middle East in hopes of finding Shams. Finally, in 1250, in Damascus, he received word that Shams had been murdered.

The end of all Rumi’s searching came with a quiet realization—one that resonates with many who have lost someone dear who nevertheless remains a merciful presence inside them—that though Shams was gone in body, his spirit had become a part of him. When Rumi wanted to feel close to Shams now, he need only look inside himself.

Since I am he, who am I seeking?

I am the same as he. His essence speaks!

While I was praising his goodness and beauty

I myself was that beauty and that goodness.

Surely I was looking for myself. From this heartbreak poured Rumi’s greatest work: countless song lyrics and poems, more than a thousand of them about Shams. Today, these are some of the most beloved verses in the world.

Though he never stopped grieving the loss of his friend—and for the rest of his life wore dark blue, the color of mourning in Persian society—in time Rumi saw that while Shams’ death signaled the end of his life’s most intense period of spiritual awakening, it was also the birth of a new chapter that allowed him to claim the mantle of a mystic elder who could guide others into their own awakening. With hard-earned wisdom, he observed that,

Where there is ruin there is hope for a treasure.

Rumi never quite regained the good graces of the conservative establishment in Konya. But as the years went on, his gospel of Love attracted a growing body of seekers from many faiths, and transformed the city into a thriving center of Sufism, which it remains to this day.

And though Rumi never stopped missing his friend, when the missing hurt too much, all he had to do was close his eyes and enter his own soul, and there Shams was again. Reminiscing about those old days, not long before his own death in 1273, he said, “I grew old mourning him. But say [his name] and all of my youth comes back to me.”

Practice

The first line of Rumi that I ever read is this one:

Where there is ruin there is hope for a treasure.

I found this timeless piece of wisdom on a windy day, years ago as I jogged around a high school track. Scrawled on a scrap of paper, it blew right across the 50-meter line. I stuffed it into my pocket, brought it home, and placed it in the top drawer of my desk. Countless times over the years, I have taken it out of that drawer and carried it around for a while, whenever I can’t see through the tangle of a present moment. While I can’t say that it instantly allows me to see through a present difficulty (though sometimes it does), by meditating on it, making it a mantra, and taking it out of my pocket to read again and again—in grocery lines, at stoplights, between sets at the gym—I am better able to face fear, grief and anxiety without giving in to the impulse to run away or avoid.

For practice today, work with this line, or another from today’s reading that might have resonated with you. Journal, meditate, talk with a friend, or just think about what Rumi’s and/or Shams’ wisdom means to you.

Holidays at Life In The City

All in person events take place at 205 East Monroe Street in Austin, Texas.

Dec. 8, 11:15 am: LITC’s original musical, Make Room In Your Heart.

Dec. 21, 6:00 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service on the longest night.

Dec. 23, 6:00 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve, an LITC tradition!

Dec. 29, 11:15 am: Welcome 2025 with a fun, casual service that includes cookies, coffee and resolution-setting. Contemplation In The City

Life In The City’s contemplative community meets regularly to practice sacred traditions like Lectio Divina and Centering Prayer. If you’re in Austin, consider joining us. Upcoming in-person gatherings are Jan. 14, Feb. 4, Mar. 4, Apr. 8, May 6. We meet at 205 East Monroe Street in Austin. Doors open at 6pm for coffee and conversation, service from 7-8pm. You might also find meaning in our monthly newsletter in which we wrestle with how to live a spiritually engaged life in the modern world. Read more here.

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2022 edition, to find out how my experience of September 11, 2001 became my gateway to Advent.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Catch a typo? Have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets for a future year? Leave feedback in the Comments below or email Greg Durham at greg@litcaustin.org.

“Where there is ruin there is hope for a treasure.” Pure gold! Thank you for that, Greg!