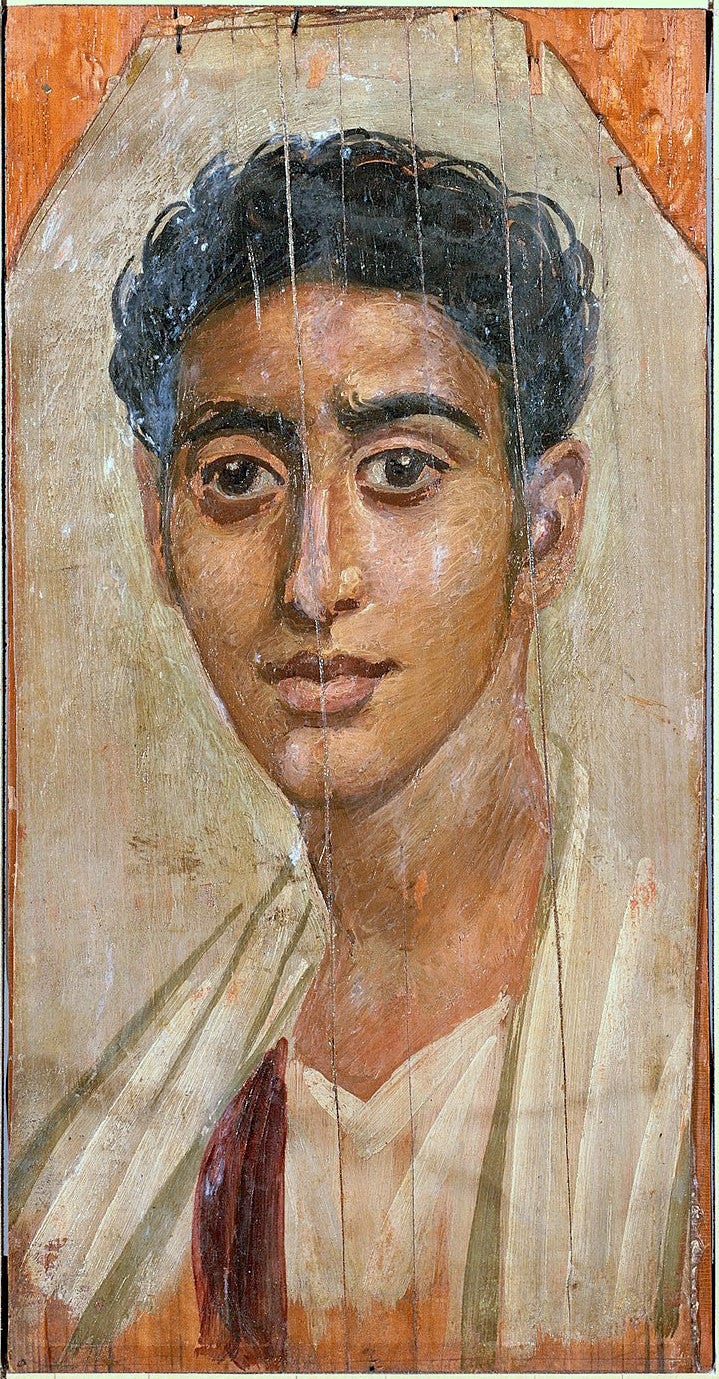

Advent Day 9: Macarius of Egypt (300-391)

In the early fourth century CE, the Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity. Up to that point, Jesus followers were a mostly poor and persecuted minority. But with Constantine’s marriage of cross and crown, they suddenly found themselves members of the state religion—a religion that, now that it was safe, the masses flocked to not out of conviction but because, well…when in Rome (literally).

While it was nice not being thrown to lions, it didn’t take long for some Christians to realize that belonging to the dominant culture had a corrupting influence. For those seeking to recapture the original fire of the Jesus movement, there was only one place to go: the desert. There, far from material temptations, Christianity’s first revival took root, led by a motley crew of Spirit-seekers now known as the Desert Mothers and Fathers. Among the most towering of these figures was Macarius of Egypt (street name: Macarius the Great).

Macarius was born in 300 CE to a family that was middle class by ancient Egyptian standards—they had a house, a couple cows and a camel. As a boy, Macarius tended the animals and generally stuck close to home. By his own account, he was an obedient child. But in his teens—like teens in all times and places—he got a little rebellious and fell in with the wrong crowd: smugglers who were moving saltpeter, a fertilizer and meat preservative, back and forth across the Nitrian Desert.

Nitria was ground zero for back-to-basics Christians. During smuggling gigs, Macarius encountered the self-styled monks and nuns who inhabited the region’s many caves, and was intrigued by their spare spirituality. These men and women subsisted on a meager diet of prayer, meditation and lentils, yet seemed somehow happier than the strivers Macarius knew back in the city…and knew himself to be.

Soon, Macarius decided he wanted some of what they had.

Macarius began dabbling in asceticism. He set up a small hut next to his parents house. He prayed. He meditated. He wove baskets from river reeds. Soon, he’d earned a reputation as a bit of a holy man. Neighbors sought him out for counsel. His family started calling him old young man due to his preternatural wisdom.

Then Macarius suffered a one-two punch. He got married but his wife died not long after, followed shortly by his parents. With no family ties to bind him, he decided to fully embrace desert spirituality. He gave all he owned to the poor—the smuggling money, the camel, hut and house—buttoned up his robe and quit town for the hermit’s life.

In the desert, Macarius took up life as a cave hermit. His days passed in prayer and meditation. He weaved baskets which he traded for food from the rare travelers who passed by. It was lonely, but he felt himself growing in wisdom and love, and closer to God. But now, in the deep desert quiet, he also realized that his mind was very noisy.

Though he’d escaped the city’s material temptations, in Nitria he faced even worse temptations—those of the spirit: anger, pettiness, lack of forgiveness, and spiritual pride. This last especially plagued him. To his horror, he came to realize that, even in absolute solitude, you can perform great feats of fasting and meditation and say it’s for God, when it’s really for your own pride, vanity and self-aggrandizement.

Rather than harshly judge himself—which may have led him to either abandon his desert life in frustration or turn the other way toward rigid fundamentalism—Macarius’s blossoming self-awareness led him to an expansive, both/and understanding of human nature. No one, including him, was good or bad; everyone was good and bad. Each heart contained everything. And each of us must learn how to cultivate the beautiful and true while releasing what is harmful to us and others.

The heart itself is only a small vessel, yet dragons and lions are there. There are poisonous beasts and all the treasures of evil. There are rough and uneven roads, there are precipices. But there too is God and the angels. Life is there, and the Kingdom, there too is light. And there the apostles and heavenly cities, and treasures of grace. All things lie within that little space.

Though Macarius kept mostly to himself, he occasionally sought out teachers, including two holy women who lived in nearby Scetis. But if Macarius thought the women would give him some spiritual silver bullet that would turn him into the perfect desert monk, he was sorely disappointed. They told him he was doing just fine with his humble rituals. What God required of him was not spiritual acrobatics, deep learning or timeless wisdom. Rather, Macarius just needed to focus on being the best version of himself he could be.

Later, recounting their meeting, he said:

In truth, the Lord seeks neither virgins nor married women, and neither monks nor laymen, but values a person’s free intent, accepting it as the deed itself. He grants to everyone’s free will the grace of the Holy Spirit, which operates in an individual and directs the life of all who yearn to be saved.

The longer he lived in his cave, and with the encouragement of teachers like the women in Scetis and the sage Abba Anthony, the more stripped down his spirituality became.

There is no need at all to make long discourses; it is enough to stretch out one’s hands and say, ‘Lord, as you will, and as you know, have mercy.’ And if the conflict grows fiercer say, ‘Lord, help!’ He knows very well what we need and he shows us his mercy.

Seeing how his desert years had changed him for the better, and continued to change him, Macarius came to believe that everyone could lead sacred lives through humility, curiosity, and a willingness to put in the work—both the internal work of contemplative practices like prayer and meditation, and the external work of right action in the world. That journey toward good, Macarius believed, had no end. This idea of unceasing spiritual progression later influenced many religious innovators including the Wesley brothers who founded Methodism.

Thanks to word-of-mouth along the trade routes, Macarius’s reputation as a holy sage grew. Eventually he earned a nickname: the Lamp of the Desert.

More and more people showed up at his cave seeking spiritual direction. He became known for his wisdom, humility and hospitality to everyone, no exceptions. He once helped a man who came to rob him pack up the goods the man wanted to steal. He nursed a pagan priest back to health after the priest had been attacked and left for dead (echoing the story of the good Samaritan). He grew a reputation as someone who accompanied people on their journeys and met them where they were.

Perhaps the most tender story about Macarius involved a young monk named Theopemptus who struggled with temptation. Macarius went to see him:

When he was alone with Theopemptus, Macarius asked, ‘How are you doing lately?’

Theopemptus replied, ‘Thanks to your prayers, all goes well.’

Macarius asked: ‘Do your thoughts not war against you?’

He replied: ‘Up to now, it’s alright,’ for Theopemptus was afraid to admit anything.

Macarius said to him, ‘I’ve lived many years as an ascetic, and am praised by all, but still the spirit of fornication troubles me.’

Macarius’s humble honesty opened a door for the young monk.

Theopemptus said, ‘Believe me, Abba, it’s the same with me.’

Macarius went on admitting that other thoughts still warred against him, until he had brought him to admit them about himself. Then he asked Theopemptus, ‘How do you fast?’

Theopemptus replied, ‘Till the ninth hour.’

‘Practise fasting a little later; meditate on the Gospel and the other Scriptures, and if a tempting thought arises within you, never look at it but always look upwards, and the Lord will come at once to your help.’

When he had given Theo this rule, Macarius returned to his solitude.

Rather than shaming the young monk, calling him out, or preaching at him, Macarius invited him into relationship. By his own example, he made it okay for Theopemptus to get real and vulnerable.

After many years in the desert, and with more pilgrims than ever seeking him out, Macarius made the difficult decision to found a community. Eventually, it grew into a town of several thousand, and included other desert sages like John The Dwarf.

There, people continued flocking to him. When they left, they carried away with them stories about Macarius, his simple lifestyle, and his humble and profound wisdom that God lived in every heart, and so every heart contained within it all it needed to transform a life. These stories spread around Africa and the Near East and on into Europe where the desert lifestyle became the blueprint for European monasticism.

Macarius lived in the community he founded for the rest of his life, save for a time he was imprisoned on an island in the Nile by Bishop Lucius of Alexandria who did not like that he could not control the free-wheeling mysticism of the desert. He died in 391 at the age of 90.

His body was buried inside the cave where he’d lived for years. At some point, seeing an opportunity, the residents of his hometown came and stole his body, took it back to the village where they buried him, and then built a big church next to the grave. He lay there for years until a Coptic pope had his remains dug up and taken to the community he’d founded (which still exists and is now named for him).

By 800 CE, the desert movement had dwindled due to Berber raids and, later, the Islamic conquest. Yet desert spirituality not only persists, it has experienced a resurgence as 21st century Spirit-seekers look to recapture the original fire of the early Jesus movement. Now, when pilgrims turn their gaze toward the desert, they still find Macarius, the flawed and friendly monk who meets pilgrims where they are, without judgement, with companionship, and with the assurance that the God they seek is already there in their hearts.

Practice

In early desert communities, repetition of short passages of scripture, or short prayers, was a common practice called hesychasm. Today, pick a short passage, prayer or quote you love. Memorize it. Then, as you go about your day, repeat it over and over, either silently or to yourself, depending on the circumstances. When you engage this practice, do so at moments when you can repeat the passage for at least two minutes. If you can find moments to do this with eyes closed, even better. Note the affect, if any, that repeating the passage has on your mood and in your body.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

Dec 21, 7 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the darkest night of the year.

Dec 23, 6 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve, an annual LITC tradition

Dec 24, 11:15 am: LITC’s regular Sunday service

Dec 31, 11:15 am: A fun, casual service with cookies and coffee to welcome 2024

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2023 edition of The Heart Moves Toward Light: Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Did you catch a typo? Do you have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets we might cover in the future? Leave feedback in comments section below or email Greg Durham at greg@lifeinthecityaustin.org.

I really enjoyed this one. I especially loved this:

“No one, including him, was good or bad; everyone was good and bad. Each heart contained everything.”

It reminds me of one of my favorite quotes by Terence:

“Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto”: I am a human being, nothing human can be alien to me.

I love Macarius! What would be some resources you would recommend to a new reader of the Desert mothers and fathers? Perhaps a biography or collection?