Advent Day 9: Teresa of Avila

The treasure is inside of us

Christ has no body but yours.

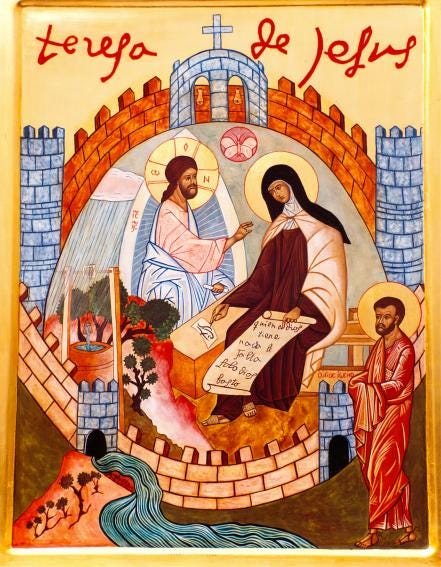

Advent Day 9: Teresa of Avila (1515-1582)

When Teresa of Avila entered a convent for the first time, it was to escape a scandal, the details of which are lost to history. Scholars, however, think that it almost certainly involved an illicit love affair. Actually, entered the convent paints a false picture. Rather, she was marched there by her father as punishment for her misdeeds. His hope was that the rigors of convent life would sufficiently scare her into doing her duty: becoming the obedient wife of an aristocrat, bearing his many children and carrying on the family name.

His strategy was an epic failure. Rather than scare Teresa straight, her time in the convent convinced her she could never let a man run her life. Instead, she set her sights on becoming a nun.

When most of us imagine 16th century convent life, we probably think of intensely pious nuns devoting their lives to fasting and prayer. The truth is much more startling. By the 1500s, Avila’s Convent of the Incarnation resembled more a sorority house than a house of prayer. Rather than cloistered living, the nuns, who all came from the upper classes, regularly entertained locals who showed up to gossip and play games. Men particularly enjoyed the company of the young nuns. Teresa—an opinionated, witty conversationalist—was the gentlemen's favorite.

Teresa loved the attention, frivolity and flirting. More than anything she desired popularity and admiration. But little by little, as the years passed, the convent’s superficiality and spiritual laziness began to wear on her. She longed for a deeper life, a deeper connection with God. But when she prayed the prayers and sang the songs of convent life, she felt nothing. Nor was she able to curb what she called her vanities. For years she went through the motions of religious life while secretly wandering a spiritual desert. Then, at age thirty-nine, her soul received a jolt.

It was a special feast day and Teresa was hurrying down a hallway on her way to the convent chapel when she spotted a statue of Jesus leaning against the wall. Irritated that someone had left the statue there, Teresa stopped to move it. But as she leaned down to grasp it, the figure of Jesus seemed to come alive, staring up at her with eyes full of compassion and pain. Overcome by a rush of love and contrition, Teresa fell to the floor in a flood of tears. She begged forgiveness for having failed to follow Jesus’s way of lovingkindness, for being gossipy and petty, her irritability with her fellow nuns, for wasting her days in shallow pursuits. She promised then and there to transform herself. For the rest of her life, Teresa considered this moment her great awakening.

Over the next couple years she often entered states of deep meditation. In these hours of stillness she arrived at the core mystical revelation that the God she had longed for was not some remote deity but an intimate Presence whose dwelling place was within her.

We need no wings to go in search of Him, but have only to look upon Him present within us…You can’t enter paradise without first entering yourself.

What dwelled in Teresa’s interior paradise was Love. The purpose of all her meditative visions (which she described as more felt than seen), she believed, was to pierce her soul so that love could flow freely in and out.

I saw in the angel’s hand a long dart of gold, and at the iron’s point there seemed to be a little fire. He appeared to me to be thrusting it at times into my heart, and to pierce my very inner depths; when he drew it out, he seemed to draw them out also, and to leave me all aflame with a great love of God.

The nun who’d once passed her days in fun and frivolity was now “satisfied with nothing less than God.”

Teresa being Teresa, she was happy to chat about her transformation. Nothing pleased her more than awakening others to the love she was now experiencing. She encouraged people to find union with God by going inside themselves through prayer and meditation. She empowered them to think of themselves as soul friends of Christ, needed by Christ to spread love.

Christ has no body but yours. No hands, no feet on Earth but yours. Yours are the eyes with which he looks with compassion on this world. Yours are the feet with which he walks to do good. Yours are the hands with which he blesses all the world.

Unsurprisingly, Teresa’s DIY spirituality did not sit well with everyone, including officials from the Spanish Inquisition who demanded that she explain herself.

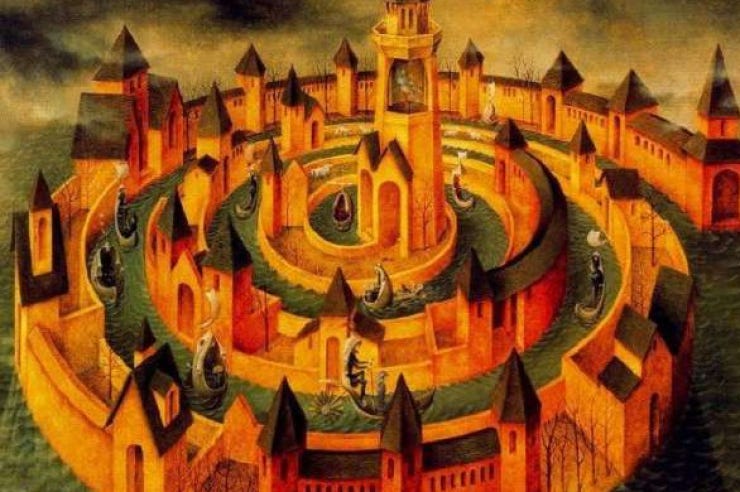

Teresa willingly complied. In books and letters, she described the soul as a great castle, and compared the process of awakening to moving from room to room, penetrating ever deeper into the castle until one arrives at the innermost room where God—the Beloved—awaits. Teresa believed that she and God depended on one another in an intimate friendship which she called a mystical marriage.

The mystical marriage…is like rain falling from the sky into a river or pool. There is nothing but water. It’s impossible to divide the sky-water from the land-water. When a little stream enters the sea, who could separate its waters back out again? Think of a bright light pouring into a room from two large windows: it enters from different places but becomes one light.

Over time, the showier aspects of Teresa’s spirituality settled into that deep peace that surpasses all understanding. But Teresa was quick to point out that a mystic’s life was never trouble-free.

…just because the soul sits in perpetual peace does not mean that the faculties of sense and reason do, or the passions. There are always wars going on in the other dwellings of the soul. There is no lack of trials and exhaustion. But these battles rarely have the power anymore to unseat the soul from her place of peace.

Everything she learned in her meditations and visions she summed up in one sentence:

The Beloved asks only two things of us, that we love him and that we love each other.

In 1560, armed with the courage of her convictions, and having dodged the Inquisition so far, Teresa took it upon herself to reform her Carmelite tradition. Her aim: to return it to the simplicity exemplified by the Desert Mothers and Fathers of the early years of Christianity.

In the decades that followed, despite being dogged by hostile political-religious forces, she opened seventeen new convents where devotional life combined community action and quiet contemplation. Along the way, she recruited a few brave souls who shared her vision of simplicity. Chief among them was her friend John of the Cross.

When they met, Teresa was fifty-two, John twenty-five. Despite differences of age, gender, temperament and upbringing (Teresa’s family was wealthy, John’s was poor), they formed a deep spiritual friendship. In John, Teresa recognized a fellow mystic who she believed could help her reform the male Carmelite orders, as she was doing for the female orders. But reforming recalcitrant monks held little interest for John. Rather, he wanted to become a hermit. Teresa asked him for one year. If, after that, he still wanted to become a hermit, then she would give him her blessing. John agreed.

They spent 1568-69 traveling together around Spain. During this time, Teresa shared with John her vision for a monastic life stripped of corrupting influences. She taught him both her principles and her prayer practices. Most of all, she modeled a life of engaged spirituality that balanced action and contemplation. Together, they worked, talked, dreamed and prayed. In the process, they became the best friend either of them would ever have. Speaking of John, Teresa echoed Aelred of Rievaulx’s belief that wherever friendship was, so was Christ:

I cannot be in (his) presence without being lifted up into the presence of God. What a glorious thing it is for two souls to understand each other, for they neither lack something to say, nor grow tired of one another.

Though she and John often came across to others as if they were out to save the world—which, in a sense, they were—Teresa offered a warning to those of us, then and now, whose activist spirit lures us into the anxious thinking that we’re never doing enough:

It’s not necessary to try to help the whole world. Concentrate on your own circle of companions who need you. Then, whatever you do will be of greater benefit.

For Teresa, the only point of living was love—of God, self and neighbor. Love was a waterwheel that, once set in motion, needed to be continually resupplied to keep turning.

Accustom yourself continually to make many acts of love, for they enkindle and melt the soul…Be assured that the more progress you make in loving your neighbor, the greater will be your love for God.

The last years of Teresa’s life was marked by both persecution and redemption. In 1576, the governing body of the Carmelites, dominated by unreformed members who were cooperative with the Inquisition, ordered her into retirement. In protest, she began a letter-writing campaign to King Philip II who, in 1579, overruled Teresa’s adversaries. Free to resume her work, she hit the road and continued founding new convents and monasteries.

It was on the road in 1582, after founding her latest convent, that she was struck ill. She held out long enough to make it back to her convent in the town of Alba de Tormes. There she died on October 4 at the age of sixty-seven. Her last words were:

My Lord, it is time to move on. Well then, may your will be done. Oh, my Lord and my Spouse, the hour that I have longed for has come. It is time to meet one another.

Practice

In her spiritual masterpiece The Interior Castle, Teresa writes:

Remember: if you want to make progress on the path and ascend to the places you have longed for, the most important thing is not to think much but to love much, and so to do whatever awakens you to love.

What or who awakens you to love? Do a meditation while holding this person/place/thing in your heart. This can be a 5-minute (or more) period of stillness, a walk, or a candle-lighting. Whatever method you choose, try to remain in that awakened state of love. If you feel yourself drifting toward other thoughts, gently bring yourself back.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

All gatherings listed below happen at 205 East Monroe Street in Austin, Texas.

Sun. Dec. 8, 11:15am: LITC's original holiday musical, Make Room In Your Heart. Sat. Dec. 21, 6:00pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate gathering on the longest night. Mon. Dec. 23, 6:00pm: Christmas Eve-Eve candlelight service...an LITC tradition! Sun. Dec. 29, 11:15am: Welcome 2025 with a fun, casual service that includes coffee, cookies, conversation and resolution-setting.

Contemplation In The City

Life In The City’s contemplative community meets regularly to practice sacred traditions like Lectio Divina and Centering Prayer. If you’re in Austin, consider joining us. Upcoming in-person gatherings are Jan. 14, Feb. 4, Mar. 4, Apr. 8, May 6. We meet at 205 East Monroe Street in Austin. Doors open at 6pm for coffee and conversation, service from 7-8pm. . You might also enjoy our monthly newsletter in which we wrestle with how to live a spiritually-engaged life in the modern world. Read more here.

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2022 edition, to find out how my experience of September 11, 2001 became my gateway to Advent.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Catch a typo? Have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets for a future year? Leave feedback in the Comments below or email Greg Durham at greg@litcaustin.org.