Every saint has a past, and every sinner has a future. Oscar Wilde

Why do you look at the speck in your brother’s eye and ignore the log in your own? Jesus

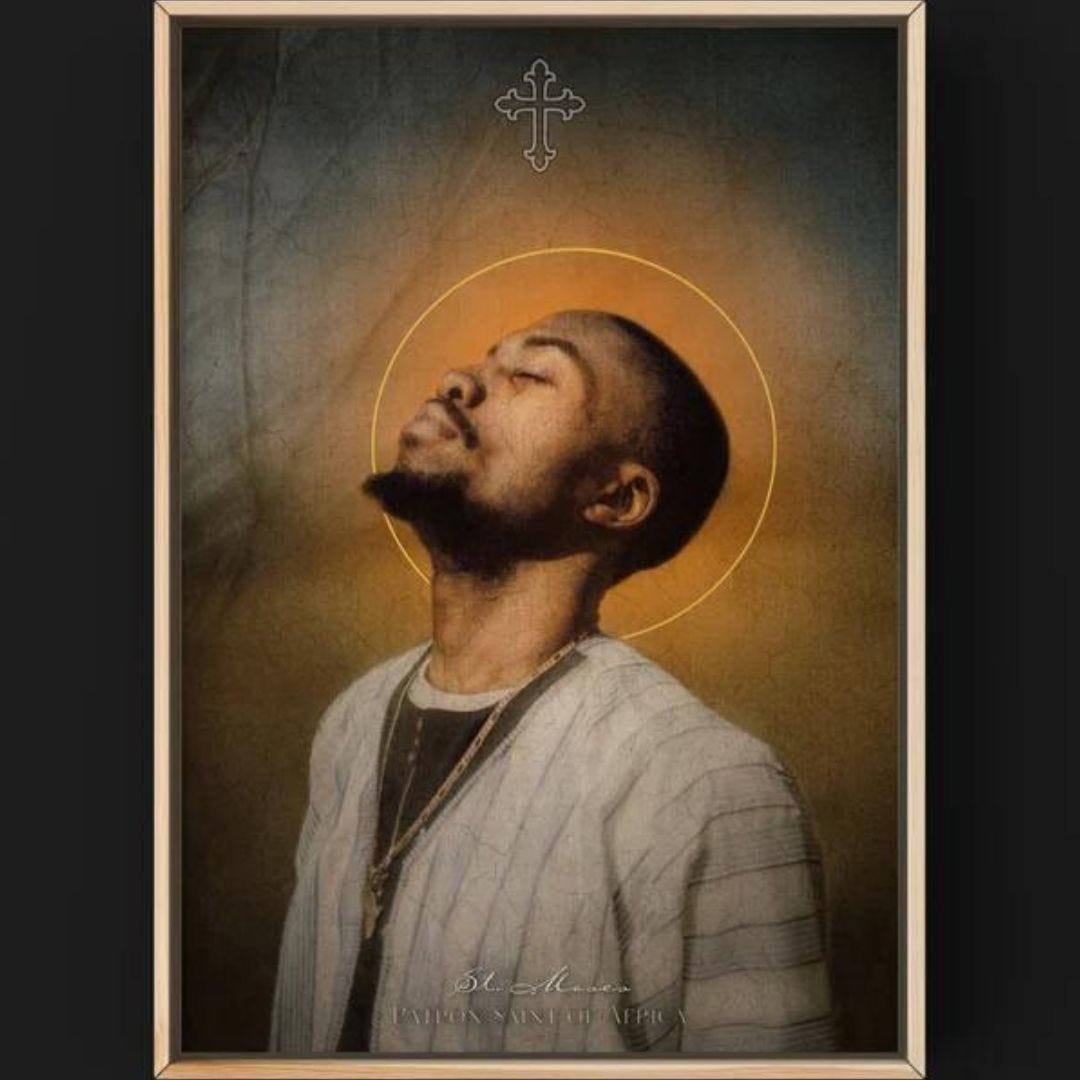

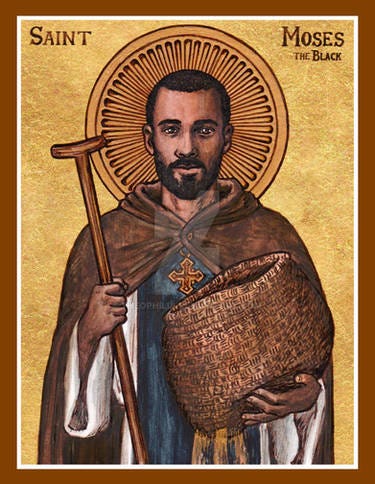

Advent Day 16: Moses the Black (330-405)

One day, the monks in the Nitrian Desert community founded by Macarius called a council to decide how to punish a brother who was accused of breaking a rule. When one of the monastery’s abbots, Moses the Black, was a no-show, someone went to fetch him. Moses said he’d be right there. A few minutes later, Moses arrived at the tribunal holding a cracked jug that was leaking water onto the floor. When the other monks asked what this was all about, Moses—who had a flair for the dramatic—said, “My sins run out behind me, and I do not see them. But today I am called to judge the errors of another.”

Moses’s spiritual agitprop, which shares much in common with Jesus’s mysterious drawing in the sand during an encounter with a woman accused of adultery, had the desired effect. Seeing the abbot respond to the errant brother not in harsh judgement but from compassion and an openness about his own brokenness, the other monks were humbled into remembering their own errant ways. In the end, they voted to forgive, rather than punish, their brother.

Moses’s early life is a mystery. We know only that he came from Ethiopia. At some point, probably in his teens, he was captured and made the slave of an Egyptian government official. But when Moses was accused of theft and murder, his master decided Moses was more trouble than he was worth and gave him the boot. Moses did then what those wanting to disappear off the map have done since, well, forever: he went to the desert.

In the Nitrian Desert of Egypt, Moses fell in with bandits. Tall, strong and brave, he soon established himself as a gang leader. It was a violent life, terrorizing caravans and robbing isolated homes. The easiest targets though were the many monks who inhabited the desert, most of them living alone in caves or in small, defenseless communities.

But eventually the hunter became the hunted. This occurred when Moses stole sheep from a man who then hired thugs to chase down the thief. This drove Moses deeper into the desert than he’d ever been. After several days running, thirsty, hungry, cold, verging on collapse, he sought refuge at the only place that would take in a stranger in the middle of the night, no questions asked: a monastery full of monks who prioritized their vow of hospitality over their personal safety.

Moses had robbed plenty of monks in his day. But now, for the first time, he paid attention to them—their prayers, daily habits and lifestyles. These brothers were about as different from him as possible. They were humble, he was arrogant. They were happy in poverty, he lived with the gnawing hunger of always wanting more. Their days passed in peace, his were cut through with violence. Around the community there was a palpable sense of calm and joy Moses had never known.

Moses quickly decided he wanted what the monks had. And like many in the first flush of spiritual awakening, he wanted it fast. He asked to join the community as a monk. But the abbot, knowing Moses’s checkered past, and wanting to be sure Moses’s was a genuine transformation and not a skin-deep spirituality, prescribed a period of three years living a monk’s life before he would be allowed to take vows.

Moses was a model monk-in-training. Whatever was expected of him, he did double. He worked harder, prayed harder and meditated longer than anyone else. And he was spiritually and intellectually gifted, able to grasp the teachings of the monastery’s trio of desert masters: Macarius, Arsenius and Isidore, the last of whom was assigned as his spiritual advisor.

But as much as he’d transformed his life, during long hours in solitude, getting to know his own heart, Moses discovered what all mystics eventually do: you can’t outrun yourself. Whatever temptations and impulses had led him to become a thief, he felt them still. In the silence of prayer and meditation he felt them gnawing at his soul. So, he doubled down on his ascetic practices. But still, his demons would not totally go away.

Seeing he was discouraged, one morning before dawn Isidore took Moses to the rooftop of the monks’ house. As the sky slowly grew brighter, Isidore said, “See! The light only gradually drives away the darkness. So it is with the soul.”

Moses got it. From then on, he gave up on perfection and, instead, embraced progress.

Like most Desert Fathers and Mothers, Moses is known by multiple names: the Black, the Strong, the Robber. Though history remembers him as the first of these, if he’d chosen, he may have picked the last. This is because, once Moses chose wholeness over holiness, he accepted and embraced the full picture of himself—good and bad, light and shadow. As spiritual practice, this was a constant reminder of where he’d come from and where he might return if he turned away from God and his spiritual disciplines of work, prayer and meditation. Moses liked to say:

Whenever the gaze strays even a little, we should turn back the eyes of the heart into the straight line towards [God].

But Moses, a keen student of human psychology, also kept the eyes of his heart on the Robber in him. The Robber was his shadow side. And he knew that when one denies their shadow—or is unable to even see it—it has a way of metastasizing. But when we share it, we allow it to be transformed. So, he bared all of himself to the disinfecting desert light. And in so doing, he modeled for others that they are—or can be—so much more than a list of the worst things they’ve done. This way of being allowed Moses to identify with others and they with him. In learning to love himself, Moses learned to love people.

Over time, the legend of the reformed bandit monk spread, and people came to the desert seeking his wisdom. Moses always welcomed them, even when it meant breaking a prescribed meditation or fast, or interrupting his prayer time. To those who sought him out, his first, and most important, advice was this:

Go sit in your cell, and your cell will teach you everything.

For Moses, the cell was both literal and figurative. Like the other monks, he had his own tiny space to which he regularly retreated, sometimes for days at a time. In that solitude, he became present to everything in the outer cell of his room but also, more importantly, the inner cell of his soul.

(This) is the place where we come into full presence with ourselves and all our inner voices, emotions, and challenges, where we strive to not abandon soul work through distraction or numbing. It is also the place where we encounter God deep in our hearts. Sit with yourself and learn every detail of that inner landscape. The more we cultivate…awareness of our thoughts, emotions, and impulses, the more we learn that they come and they go; they rise and fall in intensity. Beneath all the tumultuousness of our inner life is a profound and deep pool of stillness from which we can behold this inner drama, yet not get lured into reacting to it. We develop an inner freedom and begin to discover something of the foundation of who we are that endures no matter the constantly shifting tides around us. Christine Valters Paintner, Desert Fathers and Mothers: Early Christian Wisdom Sayings

As his fame and legend grew, Moses was sought out by ever more pilgrims and fellow monks who traveled long distances just to sit with him. This meant he had to keep on constant guard against his vanity. If he sensed an interaction, or some praise, was reinflating the ego he spent years working to deflate, he would stand up and remove himself from the situation. There are even stories of him denying he was Moses, and telling people they were crazy for wanting to meet such a fool.

Moses's relentless self-examination was the foundation of the deep grace he showed others. He refused to judge, not only because he was painfully aware of his own past, but because he believed everyone had a future. As Isidore had taught him, life was about progress, not perfection. And he modeled the adage, when you point a finger at someone else, three are pointing back at you.

Moses’s words and sayings on this subject were orally circulated during his lifetime. After his death, they were written down and joined the canon of desert wisdom.

When asked why he was not grieved by the sinfulness of others, Moses responded that when one has a corpse in their own house, they do not grieve over the corpse in the home of another.

The monk must “die to” his neighbor and never judge him at all, in any way whatever.

If we are on watch to see our own faults, we shall not see those of our neighbor…To die to one’s neighbor is this: To bear your own faults and not to pay attention to anyone else wondering whether they are good or bad. Do no harm to anyone, do not think anything bad in your heart towards anyone, do not scorn the man who does evil…Do not rail against anyone, but rather say, ‘God knows each one.’ Do not agree with him who slanders, do not rejoice at his slander, and do not hate him who slanders his neighbor.

This is what it means not to judge. Do not have hostile feelings towards anyone and do not let dislike dominate your heart; do not hate him who hates his neighbor.

If the monk does not think in his heart that he is a sinner, God will not hear him. A brother asked, ‘What does that mean, to think in his heart that he is a sinner?’ Then Abba Moses said, When someone is occupied with his own faults, he does not see those of his neighbor.

Moses refused to judge. This is not to say he didn’t think people should be held accountable, or that there weren’t consequences to actions. But Moses knew there was always more to the story, and that the past didn’t always foretell the future. As far as deeper judgement, he left that to God. What was for us to do was grace—to not let hostile feeling and hatred dominate our hearts, and to certainly never turn from the hard work of taking our own personal inventories.

In time, this gentle thug-turned-monk was elected by the other monks to be an abbot in their community. Later, he was ordained a priest, one of the highest honors of the time. It was an arc no one could have predicted, least of all Moses.

In his sixties, Moses was sent by Macarius to found a community in Petra. Due to frequent raids by roving bandits (something Moses knew a thing or two about), being a desert monk had always been dangerous. But at the dawn of the fifth century, Berber gangs were dialing up the frequency and violence of these attacks. At Petra, Moses revealed to the small group of monks who’d accompanied him that despite his decades-long commitment to nonviolence, he had a premonition that because he’d lived by the sword for so long he would also die by the sword.

In 405, Moses’s premonition came true. As raiders were about to attack his small community, the other monks wanted to take up arms, but Moses forbade it. He would not break his vow of nonviolence, even to save his own life. He told the other monks to flee, but eight remained by his side. Seven, including Moses, were murdered.

The most well-known story about Moses is the one that began this reflection. I’ve often thought about Moses holding the broken jar with water leaking out. For a long time I wondered why he wouldn’t use sand rather than the desert’s most rare and precious resource. Now I think he was trying to tell us something with the water.

He was showing us that his past, his faults, his brokenness, were precious to him. Would he change the things he’d done if he could? Undo the pain he caused? Yes. But that was not possible, So, he did the only thing he could: he embraced his past rather than running away from it.

Moses shared his shadow with the world. In sharing he fostered his soul’s continual transformation while also helping others to transform. He was extraordinarily compassionate toward others not despite his violent past but because of it. This wholeness-over-holiness approach Moses embodied is a timeless reminder that we all share a common humanity. We are all drops in the same ocean.

Advent Practice

First, receive these words from Isaiah:

In the wilderness, prepare the way for the Holy One, make straight in the desert a highway for our God. Every valley shall be lifted up, and every mountain and hill be made low; the uneven ground shall become level, and the rough places a plain.

On Day 13 of our 2023 Advent series, we reflected on the life and legacy of Bill Wilson, the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous. Moses the Black lived 1700 years before the foundation of AA, but he was already working the steps, especially number four: Made a searching and fearless moral inventory of ourselves. This step—and honestly, all of them—aren’t good just for those addicted to alcohol, drugs or gambling, they’re good for all people, always. Because we’re all addicted to something—fear, self-righteousness, anger, resentment, pride, over-achiever syndrome, despondency, etc, etc..

One option for today’s practice is to take a stab, in writing, at a searching and fearless personal inventory. But please only proceed if you can do so in a spirit of gentleness. This is not about inducing shame. It’s about honesty and taking responsibility. It’s about making our paths straight, lifting up our valleys and evening the ground of our souls. It’s about preparing the way so that we can receive the Holy. It’s to see if, like Moses the Black, our being honest about these things with ourselves can help us grow in compassion for, and connection to, others…and to ourselves.

If you do not feel prepared to do this exercise, or you feel it would not benefit you, please skip it. Instead, try one or both of the following options:

Lovingkindness meditation with Tara Brach.

Read and reflect on this poem from Steve Garnaas-Holmes:

Love would move through me but for the rubble and clutter I cling to. God, move aside what needs to be moved. Clear a way for loveliness. Fire up the gentle bulldozer of your grace. Put your little orange stakes of mercy where the road goes. Mark what needs to be cut, and cut it. Fill with your presence my pits of fear, my potholes of discouragement and despair. Level my piles of self-importance. Smooth out my bitterness, straighten what's bent. Clear out what's in the way of love. In that wilderness in me, prepare the way for your mystery to unfold.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

Dec 21, 7 pm: Blue Christmas contemplative service for the darkest night of the year.

Dec 23, 6 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve candlelight service, an annual LITC tradition.

Dec 24, 11:15 am: LITC’s regular Sunday service.

Dec 31, 11:15 am: A fun, casual service with cookies and coffee to welcome 2024.

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2023 edition of The Heart Moves Toward Light: Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Did you catch a typo? Do you have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets we might cover in the future? Leave feedback in comments section below or email Greg Durham at greg@lifeinthecityaustin.org.

Such wonderful lessons from Moses: embracing the shadow and learning to love the whole self, transformation comes gradually, refusing to judge the other, and I love that final poem from Steve Garnaas-Holmes! It definitely made it into my sermon last week!

It’s interesting to me how common the pattern is of replacing some vice with prayer and meditation only to find out that one is approaching prayer and meditation in the same way! I think it was Thomas Keating who had to eat ice cream while everyone else fasted because he was trying to “fast everyone under the table.”

Also, there’s one (maybe two) typos in this paragraph: “This occurred when a guy from whom Moses stole some sheep hired thugs to *thief down. This drove Moses deeper into the desert than he’d ever been. After several days running, *thirty, hungry, cold, verging on collapse...”