Advent Day 20: Regina Jonas and Viktor Frankl

Light in dark times

‘Blessed by God’ means to offer blessings, lovingkindness and loyalty, regardless of place and situation.

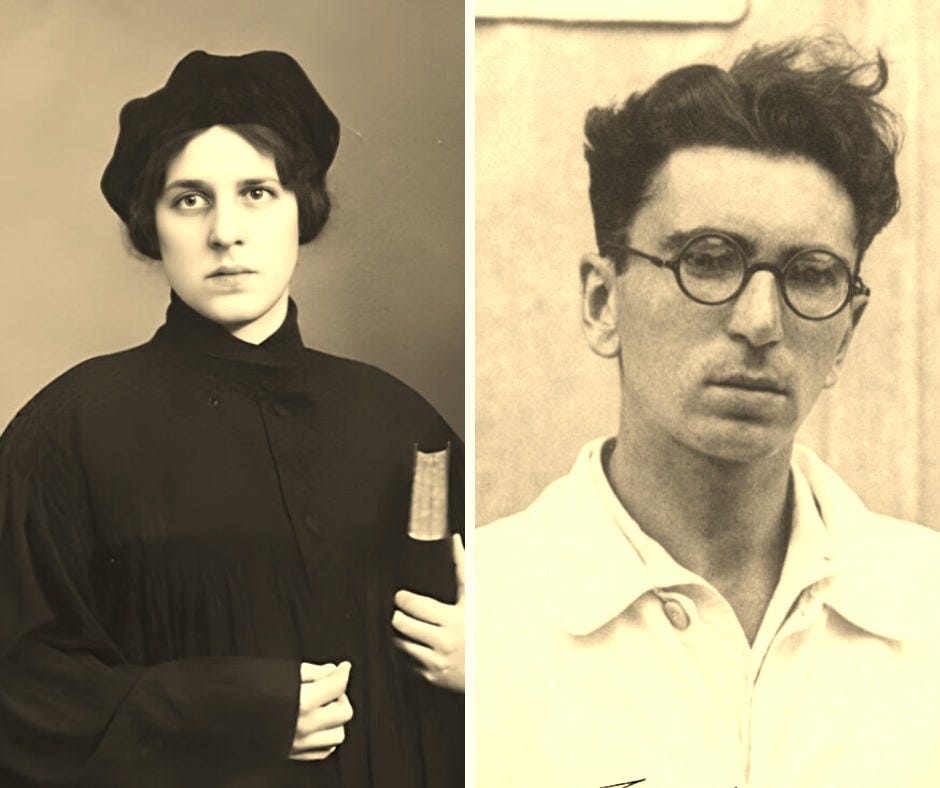

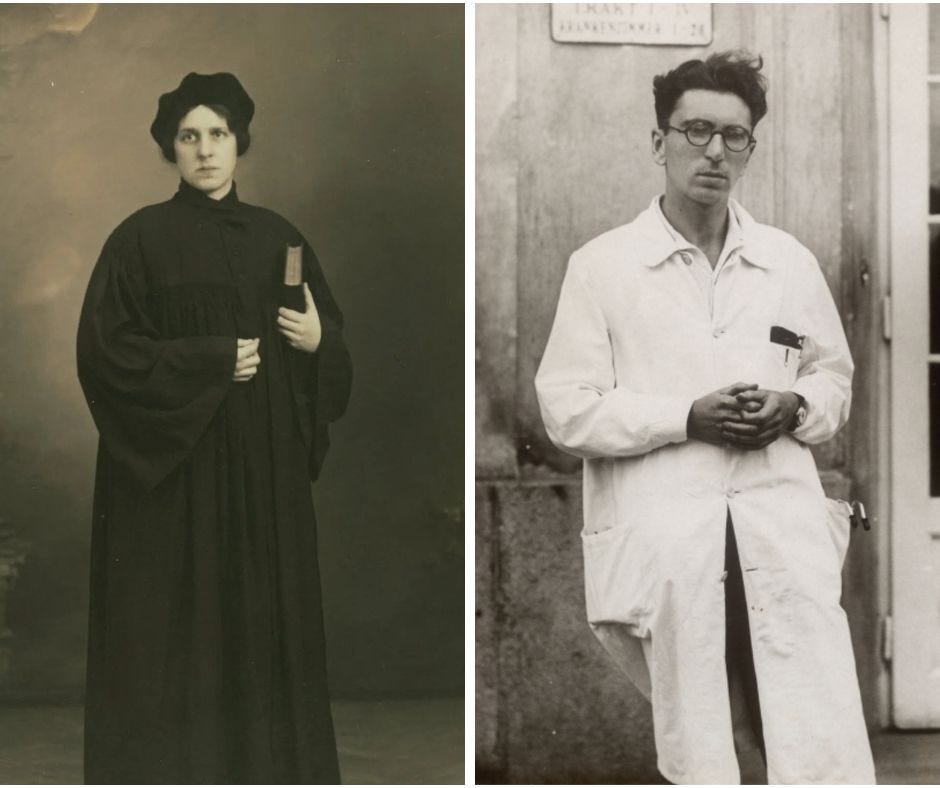

Advent Day 20: Regina Jonas (1902-1944) and Viktor Frankl (1905-1997)

The prisoners arrived dazed and confused. After stepping off the train in Terezin, Czechoslovakia they were met by Regina, a woman who carried an air of comforting authority. To those who seemed particularly disoriented she handed a questionnaire. This sheet was meant to help her and her friend Viktor gauge the mental state of the person who filled it out. How did they feel right now? Did they have any hope left for their future? How would they rate their current level of despair? Did they feel they had a reason to live?

Once the prisoners were registered in the concentration camp and assigned to barracks, Regina and Viktor pored over the questionnaires. Anyone who they suspected might be suicidal soon received a visit with an offer of spiritual and therapeutic support. In a world that had stopped making sense, Regina and Viktor had one critical job: help people find meaning; help them stay alive.

Regina Jonas was born in 1902 and raised in a poor section of east Berlin. Though her parents earned little as shopkeepers, they scraped together the money to educate her and her brother (Germany did not yet have free public education). As a teen, she considered becoming a teacher, one of the few professions open to women. But her heart wasn’t in it. Secretly, she wanted to be a rabbi.

Up to then, no Jewish woman had ever been ordained. But Regina wasn’t going to let this hold her back. In her early twenties she enrolled in the Higher Institute for Jewish Studies in Berlin. There, she declared her intention to become a rabbi. This sent shockwaves through the institution. Pushback from certain quarters was swift and severe. But Regina also received vital support from influential professors who admired her talent, grit and grace under pressure.

One of these was Talmud scholar Eduard Baneth who had been convinced by Regina’s graduate thesis in which she argued that nothing in Jewish law prevented women from being rabbis. The only barrier was prejudice.

God planted in our heart skills and a vocation without asking about gender. Therefore, it is the duty of men and women alike to work and create according to the skills given by God.

Baneth was willing to ordain Regina, but he died suddenly before doing so. In the end, Max Dienemann of the Liberal Rabbis’ Organization ordained her as a test case of women in ministry. In 1935, she became the first female rabbi in world history, shattering a glass ceiling that had existed for millennia. It was, one observer said, “an earthshaking event.”

Though Regina received a chilly reception from much of the religious establishment, those who were open to women in the pulpit, and who got to see her in action, left vivid recollections of a preacher with uncommon gifts:

The [service] was led by a young woman who radiated extraordinary magnetism through her noble biblical features and movements and through the words she spoke to the children and adults. Her personality enraptured me to such an extent that from then on I became her zealous listener. God made Regina Jonas to stand at the pulpit.

Regina greeted her own accomplishment with more of a shrug, telling one journalist,

For me it was never about being the first. I wish I had been the hundred thousandth!

We will never know if Regina might have inspired a wave of women preachers. By the time of her ordination, Nazism had engulfed Germany. Many who could left. Regina was not one. Offered a chance to escape in the late 1930s, she declined. Instead, she stayed behind to minister to the dwindling number of Jews who had not yet fled or been imprisoned.

Though she remained free longer than most, Regina, too, was finally swept up by the Nazi dragnet. On November 7, 1942 the Gestapo arrested her and put her on a train to Theresienstadt.

Theresienstadt was unique among concentration camps. Though it suffered the same overcrowding, disease and malnutrition as all camps, it was not a death factory like Auschwitz. Rather, it was a way station where prisoners lived for a time before being sent on to those camps. Daily affairs were managed by a Jewish Council. Though the Council was ultimately powerless against its Nazi overlords, this arrangement provided a terrorized people the illusion of self-determination.

Among Theresienstadt’s prisoners was an unusually large number of prominent figures—artists, academics, musicians, scientists, rabbis, doctors. These men and woman mounted a heroic campaign to create a rich cultural life inside the camp. To this end, they staged concerts and plays, gave lectures, established schools and held religious services.

Viktor Frankl and his new wife Tilly arrived in Theresienstadt in September 1942 after being deported from Vienna. In the early 20th century, Vienna was the most exciting city in Europe, home to artists and intellectuals who were breaking new ground in their fields. Two of these were the psychotherapists Alfred Adler and Sigmund Freud. Both of these men inspired Viktor to pursue psychiatry and neurology.

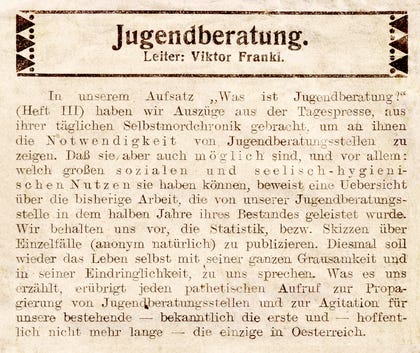

In his early twenties, Viktor made a name for himself by opening youth counseling centers. This was his creative response to an annual wave of suicides that happened at the end of the school year when grades came out. Immediately, student deaths dropped. Then, in 1931, the third year of the counseling centers, not a single Viennese student died by their own hand.

Like Carl Jung years before, Viktor eventually broke with Freud, and also Adler, and for the same reasons: what he saw as their dehumanizing view of people as no more than a handful of biological and chemical processes.

The break was dramatic. Standing up in class one day, Viktor declared that he was not just a chemical reaction. He had, he insisted, a deeper depth dimension, something which transcended his biology and chemistry. He had a spirit!

No cure that fails to engage the spirit can make us well. The aim of the therapist should be to bring out the ultimate possibilities of the patient to realize his or her latent values, remembering the [words] of Goethe: “If we take people where they are, we make them worse. If we treat them as if they were what they ought to be, we help them to become what they are capable of becoming.”

Viktor believed that we have the ability to find purpose and make meaning, even in the worst of circumstances, and it is this quality which makes us human.

Those who have a 'why' to live, can bear with almost any 'how’. Even a man who finds himself in the greatest distress…can still give his life a meaning by the way he faces his distress. By taking his unavoidable suffering upon himself, he may yet realize values. Thus, life has meaning to the last breath…Facing your fate without flinching is the highest achievement that has been granted to man.

This belief would soon be tested in ways Viktor could never have imagined.

Death was everywhere at Theresienstadt. Each day scores of people perished from sickness and starvation. Corpses sometimes lay exposed for days before being removed. In this atmosphere, Viktor knew that if anyone was going to survive, they needed to hold on to meaning. They needed a reason to live.

Viktor went about setting up a crisis intervention service similar to what he’d done for youth in Vienna. By then, Regina Jonas had arrived. As the world’s first female rabbi, her reputation preceded her. Curious, Viktor went to see her give a sermon. He was so moved by her spiritual depth he asked her to join him in his efforts to save their fellow prisoners.

Viktor’s core belief was that "Life is never made unbearable by circumstances, but only by lack of meaning and purpose.” With that in mind, he and Regina tried to help those around them find their meaning and purpose in the midst of seemingly meaningless brutality and purposeless days where many felt they were just waiting to die.

They counseled their fellow prisoners that, to get through each day, they should make a practice of focusing on their deepest desires like reuniting with loved ones, returning to their homes, or completing unfinished tasks (Viktor himself yearned to finish a book he’d started back in Vienna). They encouraged simple acts of kindness in the camp in order to build a sense of fellowship and community, which they knew was key to helping people find the will to keep going. They instructed them to lift their eyes and look around at the beauty that still, improbably, remained.

This was spiritual rebellion at its deepest. The Nazis had taken nearly everything from them, but they could not take away their freedom to admire a sunset or a flower in spring, or to love one another. They could not touch the heart of life.

In her sermons at Theresienstadt, Regina sought to connect others to that heart, and to consider what it asked of them in this, their most terrible trial:

‘Blessed by God’ means to offer blessings, lovingkindness and loyalty, regardless of place and situation. Humility before God, selfless love for His creatures, sustain the world. It is [our] task to build these pillars of the world…Our work in Theresienstadt, serious and full of trials as it is, also serves this end: to be God’s servants and as such to move from earthly spheres to eternal ones. May all our work be a blessing for [our] future, and the future of humanity…

Life at Theresienstadt took a bizarre twist in 1943. For years, the Red Cross had been routinely denied access to the concentration camps. But now, smelling a propaganda opportunity, the Nazis decided to let them in.

Over the winter of 1943-44, Theresienstadt was transformed into a model camp. To reduce crowding, 8,000 prisoners were shipped to Auschwitz. Then, transports both into and out of the camp were halted. For those remaining behind, the quantity and quality of food increased. Prominent prisoners were moved to new and better accommodations. Streets were tidied up. Fake schools and shops were established. A robust schedule of cultural events was created.

The Red Cross had many concerns about the camps. The main one, however, was the suspicion they were being used as mere way points from which prisoners were then sent on to places like Auschwitz. But at Theresienstadt, the smoke-and-mirrors worked. When the Red Cross toured the camp in June 1944 they saw a tidy, well-ordered village. In his report, the Red Cross representative noted that no one was deported from Theresienstadt. Of this visit, Leo Baeck, a prominent spiritual guide and one of Regina Jonas’s early mentors, later said, “The effect [of this visit] on our morale was devastating. We felt forgotten and forsaken.”

Camp life quickly deteriorated after the Red Cross left. As German defeat began to look inevitable, the Nazis ramped up their extermination process. In September, twenty percent of the Theresienstadt population was deported to Auschwitz. A cloud of doom hung over the camp.

Through it all, Regina and Viktor worked heroically to help people hold on to their sense of dignity and self-worth. This was not a denial of what was happening. Quite the opposite. In Viktor’s words, they were helping their fellow prisoners, as best they could, to “Face [their] fate without flinching.”

In late-October 1944, Regina and Viktor, along with nearly all the remaining prisoners of Theresienstadt—19,000 souls—were loaded onto cattle cars and sent to Auschwitz. Regina was murdered the day they arrived. Viktor, miraculously, survived.

Years after the war, another survivor of the conflict, Hannah Arendt, wrote

Even in the darkest of times we have the right to expect some illumination, and that such illumination may well come less from theories than from the uncertain, flickering, and often weak light that some men and women, in their lives and their works, will kindle under almost all circumstances and shed over the time span that was given them on earth.

She might as well have been writing about Regina Jonas and Viktor Frankl, who were the brightest of lights in the darkest of times. Through their friendship and partnership, and in an act of spiritual resistance, they labored to help countless people who’d lost everything hold on to the one thing that could never be taken away without permission: their humanity. May their memory be a blessing.

Practice

For today’s practice*, first read this quote from Viktor Frankl:

Say yes to life in spite of everything.

Now, ask yourself this question (in a journal, if possible, though this can also be a mental exercise):

What am I grateful for today?

List five things. Don’t be afraid to include things that were accompanied by suffering or pain. For example, a sense of liberation may have been preceded by a divorce. Or a newfound appreciation of life may have come from a serious illness.

Now ask:

What's being asked of me today?

This is not a to-do list, but what your to-do list is calling you to. So, for example, caring for a child may be asking love of you. Picking up litter around your neighborhood may be a call to communal care. Calling a sick friend for ten minutes, when you feel you don’t have time, may be calling you to think about priorities.

*This practice was inspired by a May 8, 2024 conversation on Father Bill W.’s Two Way Prayer podcast in which he and therapist Tom Lavin discussed Viktor Frankl.

Holidays at Life In The City

All in-person gatherings listed below happen at 205 East Monroe St. in Austin, Texas.

Dec. 8, 11:15 am: LITC’s original musical, Make Room In Your Heart. Dec. 21, 6:00 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the longest night. Dec. 23, 6:00 pm: Our annual Christmas Eve-Eve service. Dec. 29, 11:15 am: Welcome 2025 with a fun, casual service that includes coffee, cookies, conversation and resolution-making.

Contemplation In The City

Life In The City’s contemplative community meets regularly to practice sacred traditions like Lectio Divina and Centering Prayer. If you’re in Austin, consider joining us. Upcoming in-person gatherings are Jan. 14, Feb. 4, Mar. 4, Apr. 8, May 6. We meet at 205 East Monroe Street in Austin. Doors open at 6pm for coffee and conversation, service from 7-8pm. You might also find meaning in our monthly newsletter in which we wrestle with how to live a spiritually engaged life in the modern world. Read more here.

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2022 edition, to find out how my experience of September 11, 2001 became my gateway to Advent.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Catch a typo? Have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets for a future year? Leave feedback in the Comments below or email Greg Durham at greg@litcaustin.org.

Such an amazing story about two extraordinary people. And you tell it in such a compelling way Greg. Thank you for your careful research in bringing these stories to life.

I hadn’t heard of Regina! What an inspiring story of giving people hope and agency even in an impossible situation.