When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why they are poor, they call me a Communist.

Advent Day 23: Dom Helder Camara (1909-1999)

One stormy night in the 1970s, an assassin crept up to a simple wood house behind a church in northeastern Brazil. His target was the so-called Bishop of the Slums. For years, this priest had been a thorn in the side of the military dictatorship, publicly criticizing it and calling for its demise. The ruling generals wanted nothing more than to take the priest out. Now, the hit man reached the door, knocked and drew his gun. When the door opened, there stood Dom Helder Camara, all five-feet-nothing of him, in his simple brown cassock and wood cross.

“Dom Helder, I have come to assassinate you,” the hitman announced.

The priest smiled. “Well then, you will send me straight to the Lord.”

Undone by the beatific peace of his intended target, the hitman lowered his gun and began to sob. “I can’t kill you. You belong to God.”

That Dom Helder Camara belonged to God was never disputed, not even by military dictators and would-be assassins. From a young age, he had the mystic’s eye, seeing Christ in all of creation, and God in every moment.

Any time, day or night, at home or in the street, wherever we are, we live bathed in God.

As such he had an intense compassion for, and identification with, those who suffered. When, at age fifteen, he announced his intention to become a priest, his father warned that he would no longer belong to himself but to God and the people. Helder replied that this was exactly what he wanted.

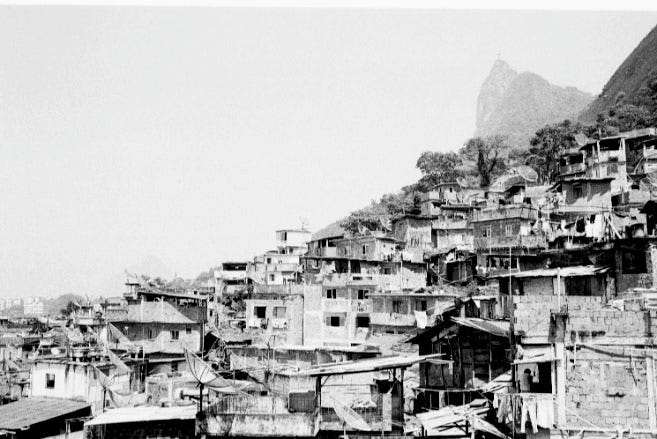

As a young priest, Helder was sent to work organizing and distributing charitable donations in Rio de Janeiro’s teeming, hillside favelas. There, rather than remain aloof, as had most other priests who’d served the slums, he lived among the residents. He dressed in a plain robe and wore a simple wooden cross. He donated his car to be used as an ambulance. At two each morning he rose to pray, write and meditate for three hours before getting to work feeding his neighbors. Whether in action or contemplation, his very life was an answer to Meister Eckhart’s three-pronged question:

What good is it to me if this eternal birth of the divine Son takes place unceasingly but does not take place within myself? And what good is it to me if Mary is full of grace if I am not also full of grace? What good is it to me for the Creator to give birth to his Son if I also do not give birth to him in my time and my culture?

Helder birthed Love in himself and then carried Love out into his time and culture.

After a few years in the slums, Helder came to realize that charity, though serving a pressing need, failed to address the root causes of poverty. He took it upon himself to get to those roots.

Since education was a barrier to employment, and most of the population he served was illiterate, he launched programs to teach reading and writing. Housing was also a major barrier to stability, with most families living in tin shacks that damaged by Rio’s frequent thunderstorms. So, Helder launched a housing program to build permanent dwellings. And since all this entailed far more work than he could do alone, he enlisted locals, particularly women, most of whom had never served in the male-dominated church structure, to create community groups that they then ran themselves, offering them a sense of empowerment and hope. This talent for empowering and working alongside people would be a hallmark of his life and spirituality.

When we are dreaming alone it is only a dream. When we are dreaming with others, it is the beginning of reality.

As helpful as all this was, Helder came to see that the roots of poverty sank even deeper than he’d first thought. The real culprit, he came to believe, was institutional neglect, racism and injustice. The government, society, and even his beloved church created and fostered the conditions that made and kept most people poor…and a few people rich and powerful. All his work to educate, feed and house would only be Band-aids on a gaping wound until the big problems were solved.

In 1956, Helder gained a powerful ally when Juscelino Kubitscheck was elected President on a platform of economic and social modernization. Over the next five years, Helder—now a Bishop—advised the President on ways to permanently reduce poverty through institutional change.

Though Helder was now moving in the halls of power he continued to forgo the pomp, ceremony and privileges of his position, opting instead to remain in the favelas. By the 1960s, his compassion, advocacy and powerful example of humility had made him the most beloved figure in Brazil, with millions of devotees, particularly among the country’s lower classes and reform-minded.

But his advocacy was not limited to Brazil. As bishop of Rio, he attended all four meetings of the Vatican II Council in Rome which sought to bring Catholicism into the modern age. At the final council he led forty bishops into the catacombs of Rome to create the Pact of the Catacombs which called on all bishops to live without honorific titles, privileges and material ostentation.

Despite his international profile, he remained a profoundly humble servant of God. When asked by Mother Teresa how he kept so humble despite his popularity, Helder replied humorously that he liked to picture himself in the story of Jesus’s triumphal entry into Jerusalem—not as Jesus but as the ass Jesus rode in on.

Though Helder’s work earned him many supporters it also earned him enemies among the elite. Asking the powerful to share their privileges is never a recipe for keeping your job, or even staying alive (see: Jesus). Nor is it a recipe for remaining in elected office, which Brazil’s President Joao Goulart learned in 1964 when several state governors, industrial oligarchs, and the heads of the Catholic church in Brazil organized a military coup. What followed was a brutal dictatorship lasting two-decades in which reformers were jailed, murdered or swept out of public view. This included Helder who was relieved of his bishopric in Rio and shuttled off to the remote, rural province of Recife.

If the dictators thought that removing Helder to the provinces would end his advocacy for the underprivileged, they were sorely mistaken. As it turned out, Recife proved fertile, if dangerous, ground for Helder’s social justice movement. There, he lived as he had in Rio, establishing organizations to educate and feed the poor, lobbying for land reform, speaking out for democracy, and opting to live in a small bungalow behind the local church rather than in the episcopal mansion. Proclaiming himself a pastor for all, he often found himself in the odd position of preaching in the same service to both revolutionary locals and the dictatorship’s regional military representatives. He did this despite great personal risk and even as colleagues engaged in similar work were imprisoned, tortured and murdered by the state. When asked how he was able to preach to all, he said:

In the heart of a priest, there cannot exist a drop of hatred. We share the same Father, we are blood sisters and brothers, in the blood of Jesus Christ.

In 1970, after delivering a speech in Paris in which he denounced government-sponsored torture, the dictatorship banned him from further travel, and from appearing on radio or television. The government even worked behind the scenes internationally to insure that he did not receive the Nobel Peace Prize for which he’d been nominated. Newspapers were not allowed to mention his name. The most beloved man in Brazil had become a non-person. Even the Vatican turned a cold shoulder, though Pope Paul VI was curious enough to once ask Cardinal Arns of Sao Paolo to tell him about the courageous and seemingly-tireless Helder. In his reply, Arns captured the great sweep of this one small man:

Dom Helder is a poet, a mystic and a missionary. As a poet he knows how to say things and the people understand what he says…As a mystic, he lives praying, and passes his whole life always with God…But he is also a great missionary, a man who brings the ideas of God to the hearts of people. I have no doubt that he is the greatest man of the Church in Brazil.

Helder survived the dictatorship which ended in 1985. Though he was free to resume speaking and traveling he mostly opted to remain close to his home and church. When he died in 1999, condolences and remembrances poured in from around the globe, and the democratically-elected President of Brazil declared three days of public mourning.

Helder left behind a legacy of courage, humility and persistence. He also left behind more than seven thousand prayers like the one below, each of them inviting us to move ever deeper into life by moving our love ever further out into the world.

Let us open our eyes. Let us begin at once to fight our selfishness and come out of ourselves, to dedicate ourselves once and for all, whatever the sacrifices, to the nonviolent struggle for a more just and a more human world. Let us not put off the decision till tomorrow. Let us begin today, now, intelligently and firmly. Let us recognize our brothers and sisters who are called, like us, to give up their ease and join all those who hunger for the truth and who have sworn to give their lives to make peace through justice and love.

Practice

Dom Helder Camara cherished the words of Paul from his letter to the Romans:

Each one of us is joined with one another, and we become together what we could not be alone.

He believed down to his bones that everyone had a role to play in community, and that working together wasn’t just good policy but absolutely necessary:

When we are dreaming alone it is only a dream. When we are dreaming with others, it is the beginning of reality.

As such he was constantly making connections with and for people, always seeking to empower people—especially women, the poor, and the laity—so that their gifts, talents and energies might be offered for the greater good.

Think of something you do that is important to you, that you’re passionate about. This could be your work or church, a way you volunteer, a service you provide a neighbor, a project you’re working on. How might you increase your reach and impact, or reach your goals, by partnering with other people? Just to give an example from my life, my family picks up trash around my part of Austin. I’ve made it a goal in 2023 to try and build a network of neighbors to “adopt” streets so that we can cover more ground than is possible with just my family.

Set your intention by writing it down in a journal or meditating on it.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

Dec. 21, 7:30 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the longest night of the year.

Dec. 23, 7:00 pm: Our annual Christmas Eve-Eve service.

Dec. 25, 11:15 am: Celebrate Christmas morning with your church family.

Jan 1, 11:15 am: A quiet, contemplative service to welcome 2023.

Catch Up On Recent Posts

Read the Introduction to The Heart Moves Toward Light: Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets.

Recent posts can be found in our Archive.

Wow. Powerful story!!