I first fell in love with Advent during the terrible holiday season of 2001. At the time, I was living in New York City, not far from the World Trade Center. On September 11th, when the first plane hit the North Tower, the roar of the impact echoed through my neighborhood, rattling the apartment windows and shaking the floor of my apartment. Like everyone, I assumed it was a terrible accident. Then the second plane hit.

Within minutes, it seemed like all of Manhattan had poured into the streets. On my corner, I stood with neighbors and watched flame and smoke spew from the gaping wounds in the towers. I thought of the many people I knew who worked in those buildings, especially those with offices on high floors, like my friend Jack who was employed by financial services firm Cantor Fitzgerald. Suddenly, I was gripped by that primal human urge to rush in and help…to just do something—anything—other than stand helpless on my corner and watch.

I ran back to my apartment, grabbed my bike and camera—another, perhaps more modern, primal urge: to document what we’re seeing, even the horrible things—and headed south. The camera saved my life. Only ten blocks from the World Trade Center, I stopped to snap pictures of the tidal wave of office workers coming at me. I was still clicking when I heard a loud crack. In an instant, everyone around me was sprinting as the South Tower collapsed.

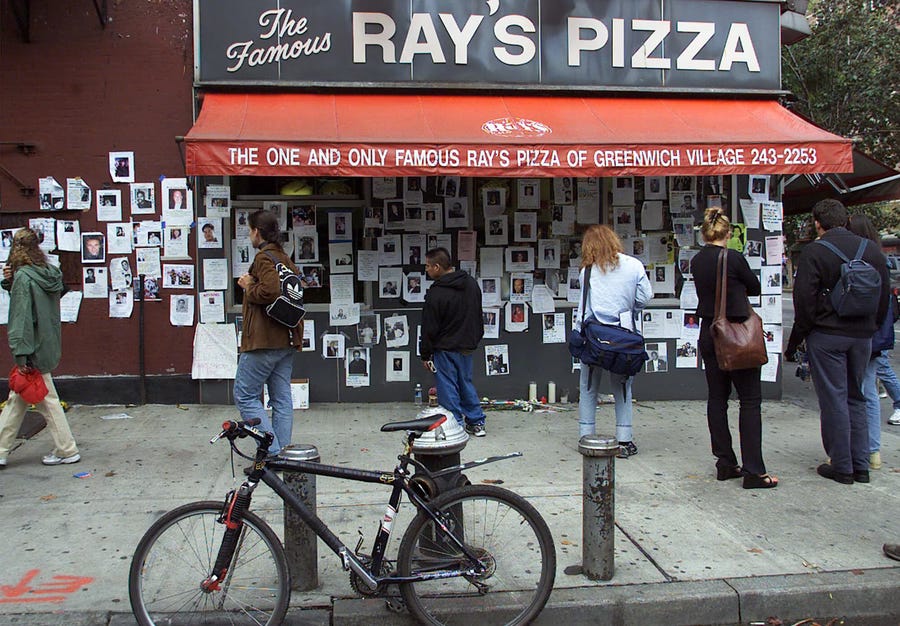

The months following the attack were tough for everyone. In a flash, we’d entered a terrifying new era where anxiety reigned. For New Yorkers, there was no escape from what had happened. I woke each morning to a fresh layer of ash on my windowsill, from the smoldering rubble. I developed a hacking cough from that ash. My pulse raced whenever a plane seemed to fly too low overhead. I began wearing earplugs in an attempt to block out the constant sirens as police responded to the daily barrage of bomb threats around the city. And though all my friends who worked at the World Trade Center survived (Jack was late to work that morning. His tardiness saved him. 658 of his Cantor Fitzgerald coworkers were killed), the faces of those who hadn’t were everywhere, taped to construction barriers, signposts, businesses, inside subway cars.

My job in book publishing—an industry I loved—didn’t offer much relief. Like so many other industries, it was hit hard by the economic reordering that came in the wake of the attacks. In late October, with budgets shrinking fast, I was laid off.

I spent the early weeks of my layoff wandering the streets of Manhattan. The city was wrapped in gloom as the initial we’re-all-in-this-together spirit morphed into a fog of fear. Everyone was on edge. On the TV news, on posters, and in recordings played ad nauseam in subways stations, we were told to stay alert and suspicious. If you see something, say something was the dominant mood. Suddenly, everyone was a potential terrorist.

As November deepened, I found myself craving Christmas. The city is magical that time of year. And if there was one thing I thought we needed in that dire fall of 2001 it was magic. I was convinced that a straight-no-chaser shot of Christmas fantasy was just the trick to drive away our collective blues.

Then something strange happened.

Thanksgiving weekend, I went with friends to see the Rockettes at Radio City Music Hall. I went ice skating in Central Park with a teen I was mentoring. I stopped by a store in Greenwich Village to get a gift for my sister. I tuned my radio to the wall-to-wall carols on WQXR. I baked sugar cookies and decorated my tree. I did everything that had always made me so happy during the holidays, and felt…nothing. There seemed to be no cure for my blues. When Judy Garland sang through my speakers that next year all our troubles would be far away, I almost threw the radio out the window.

Then I thought of the one thing I hadn’t yet tried—something I hadn’t done in years but which, in previous times of need, had brought me comfort: church.

The first Sunday in December, I stepped into the Church of the Ascension, an Episcopal congregation on Fifth Avenue. It was my first time in years in a church other than as a tourist in Europe.

As I settled in a middle pew, two things struck me:

The gorgeous Neo-Gothic architecture.

There was not a single Christmas decoration in sight.

I was confused. By December, the Methodist church I attended as a kid was always tricked out with garlands, wreaths and candles. Adding to my confusion that day, the choir sang not cheery carols but hymns proclaiming the coming of a Christ who would judge the quick and the dead. As if that were not bad enough, the sermon was not a heartwarming tale of Christmas charity, but about the prophet Jeremiah witnessing the destruction of Jerusalem, and how we all walked in the shadow of death.

I almost got up and left. I’d been living in the literal shadow of death for three months and had come to church for escape, not reality. And I might have if it wouldn’t have required shoving past a pew full of people. Instead, I hunkered down and resolved to ride out the service.

I’m glad I did, for that day changed for me not only the holiday season of 2001, but every holiday since.

By the time the service ended, a wet snow was falling. I pulled on my puffy North Face jacket and dashed down to the fellowship hall to grab a to-go coffee before fleeing the depressing, Christmas-less church. However, as often happens when you’re the fresh face in church, I was cornered by some members eager to chat—an elderly couple who’d been members of Ascension since the 1940s.

A couple minutes into our conversation, I ventured to ask why there were no Christmas decorations. They looked at me with that mix of patience and pity usually reserved for children who should know better. “Because, dear, it’s not Christmas,” the woman said. “It’s Advent.”

Huh? Advent?

As they’d say in New York, what did I know from Advent?

Up to that day—and maybe like you—my sole reference for Advent was the calendars with all the little doors hiding milk chocolates behind them. Advent, as I vaguely (and mistakenly) understood, was a warm-up for Christmas: the time to buy gifts, wrap gifts, wonder how to pay for said gifts, attend parties, don ugly sweaters, drink and eat too much.

That’s Advent. Right?

What I did not know then, but soon learned, is that Advent is, indeed, a warm-up for Christmas, but not how you might think.

Advent kicks off the Christian New Year. It starts (in the northern hemisphere) at the darkest time of year, and the further we venture into Advent, the deeper the darkness grows. The word itself comes from the Latin adventus which means that which is to come. For pre-20th century, pre-Industrial Christians, it was a time to engage in quiet prayer, humble reflection and acts of service as they contemplated three eras: the past when God showed up in the world through Jesus on the first Christmas; the present where God walks with us in our fears, failures, hopes and joys; and the future when mercy and justice will reign without end. Advent prepares us to receive Christ in our hearts so that Christ can incarnate in us.

Now, if quiet prayer and humble reflection is not what comes to mind when you think New Year’s, you’re not alone. If you’re also wondering how a season which mandates we meditate on our hopes and longings turned into milk-chocolatey calendars, me too. And if you’re thinking that reviving Advent takes some intention in the face of the consumer feeding frenzy that is the modern Advent/Christmas season, then you’d be right.

Episcopal priest Fleming Rutledge says of Advent:

It requires courage to look into the heart of darkness, especially when we are afraid we might see ourselves there… The authentically hopeful Christmas spirit has not looked away from darkness, but straight into it. The true and victorious Christmas spirit does not look away from death, but directly at it. Otherwise, the message is cheap and false.

English mystic Caryll Houselander (Day 2) gives Advent a more poetic spin:

Advent is the season of humility, silence and growth… Advent, like winter, is a time of hiddenness and darkness. The leaves are stripped from the trees, and the trees look dead. We know life is hid within them, but it’s hard to tell. One can only have hope if you remember Spring is coming. The same is true for us. We must have faith in the middle of the darkness.

She continues:

It is a time of darkness, of faith. We shall not see Christ’s radiance in our lives yet; it is still hidden in our darkness; nevertheless, we must believe that He is growing in our lives; we must believe it so firmly that we cannot help relating everything, literally everything, to this almost incredible reality.

Over the years, I’ve come to think of Advent as:

A gate we are invited to walk through into a more full and rich human experience.

A sacred dare to have faith that everything we’ve been, are and will be—all we’ve lost and gained in the past, all our present pain and joy, and all our hopes for the future—add up to something that can be transformed and made new.

A counter-cultural invitation to slow down and be the calm in the Christmas storm of exhausted excess.

A mirror in which to honestly view ourselves and the world.

A refusal to reach for, or accept, easy answers, solutions, blame or anger.

A challenge to plant a garden in our souls where hope, love, joy and peace thrive.

But that’s now. In 2001, I wasn’t thinking any of this.

Back then, curiosity piqued by my visit to Church of the Ascension, I went to the local library and checked out the only book on the shelf about Advent, a scholarly title written in the 1970s by a former monk. In one of the chapters, I found a medieval practice that I started doing that very day, and still use all these years later during Advent. It’s simple and anyone can do it: light a candle, close your eyes, and whisper Come, Lord Jesus, rest in silence for thirty seconds, then repeat for as long as you like. This is a tried and true practice you can do anywhere—at a stoplight, in a grocery store line, on a city bus (minus the candle, of course). During Advent 2001, I practiced this simple ritual twice a day.

I also learned about Lectio Divina, an ancient way of reading and praying the scriptures. Interested in giving it a go, I took my Bible off the shelf where it had sat untouched for longer than I care to admit, and explored the birth narratives of Matthew and Luke. These were stories I thought I knew. But through Lectio, they took on a whole new depth dimension.

During Advent 2001, my budding practices sometimes brought me peace. Sometimes I felt energized, giddy even with the excitement of new spiritual discovery. Sometimes I felt nothing. And then other times—and this really took me by surprise—I ended up in tears.

I realized I’d spent months running from September 11th. Only the more I ran from that day, the more I ran into it (yes, this is covered in chapter one of all self-help books about facing pain and trauma…I’m a slow learner). But now, in the quiet of meditation, I let in the memories of 9/11 and all that had passed in the months since. Day by day, little by little, the pall I’d been under began to lift. Or, at least, I was learning to not be swallowed up by the gloom.

This was the paradox; by letting the dark in, I began to see glimmers of light in those four Advent pillars: hope, love, joy and peace. When it finally came, that Christmas wasn’t the happiest I’d ever had—it was more like Leonard Cohen’s cold and broken hallelujah. But a hallelujah nevertheless.

In the decade or so that followed, I mixed and matched Advent practices: lighting candles, journaling, prayer walks around my neighborhood. Then, in 2013, my Advent got a boost when a friend gifted me a collection of the works of 16th century Spanish mystic John of the Cross (Day 6). John’s love poems to God, some written under the pain of imprisonment and persecution, come alive with imagery of darkness as a necessary stage on the journey toward light. Lines like The endurance of darkness is preparation for great light and In the dark night of the soul, bright flows the river of God, are tailor-made for Advent.

I began to explore the rich tradition of Christian mysticism. Through John of the Cross, I met his mentor Teresa of Avila (Day 10), then Therese of Lisieux (Day 13) who loved Teresa, then Dorothy Day (Day 11) who chose Therese as her personal patron saint. I read the Cloud of Unknowing which introduced me to an ancient type of Christian contemplation called Centering Prayer which, in modern times, was revived and transmitted by Thomas Keating (Day 19). Eventually, my interest in mysticism led me to a two-year course of study with modern mystic Richard Rohr (and other wise teachers) at the Center for Action and Contemplation in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

These mystics, saints and prophets have become soul friends and trusted companions on my yearly Advent path. Each of them, in their unique way, challenges me to slow down, look around, go deeper, awaken to God’s incarnate presence, and contemplate how I can give birth to Christ in my own soul.

Since the subtitle of this book is Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets, and since many have an idea what saints and prophets are, but are less certain about mystics, it may be helpful to offer a definition. From the Oxford Dictionary:

…a mystic is a person who seeks by contemplation and self-surrender to obtain unity with or absorption into the Deity or the absolute, or who believes in the spiritual apprehension of truths that are beyond the intellect.

In other words, mystics know what they know about God not through creeds or affirmations of faith, but through deeply felt personal experience of God’s presence in their lives. This experience of God’s intimate presence causes a kind of spiritual awakening that grows over time. Thus awakened, they live in fidelity to their intimacy with God, even at times when God may seem distant or lost to them.

For me, mystics are bright, shining stars whose lights guide us home to God. And while some, particularly readers from traditions where saints are formally canonized, may disagree, I feel that the lines between mystics, saints and prophets are so blurred as to be non-existent. Mystics are saints who, by the witness of their lives and work, are prophetic. So, from here on out, for the sake of simplicity, I’ll mostly use just one of these terms at a time.

It also bears saying: saints, canonized or not, are not saints. They are flesh and blood people. Some of those featured in this book, like Thomas Merton (Day 9) were well-known in their lifetimes. Others, like Meister Eckhart (Day 4) and Julian of Norwich (Day 8) were notable but fell into obscurity only to be rediscovered centuries later. Some, like the author of the Cloud of Unknowing (Day 24) are unknown.

Everyone featured in this book was someone who got up in the morning, ate meals, laced up their boots and faced their joys and longings, fears and failures, irritations and aspirations, boredom and busyness. They did not live in perpetual bliss. What made them mystics was their flashes of intimacy and union with God—what Julian of Norwich called oneing.

Though most (but not all) of those found in these pages were Christian, they did not need the church to mediate between them and God. Their experiences were self-verifying. They knew these experiences to be true and beautiful because their awakened hearts told them it was so. They found God in the unlikeliest of places: a concentration camp (Etty Hillesum, Day 5) a tree (Howard Thurman, Day 3) and in the struggle for equal rights (Pauli Murray, Day 7).

My hope for this book is two-fold: to inspire you to learn more about Advent, and to introduce you to soul guides who will inspire, challenge and comfort you, as well as awaken you to your own mystical heart. Since Advent ranges from twenty-two to twenty-eight days, depending on the year, I’ve included twenty-eight daily entries (plus one for Christmas), to account for those years when the season lasts longest.

My list of beloved mystics is endless, so deciding who to include was tough. You may find some I’ve chosen surprising, even controversial. While most books of this nature lean heavily on figures from the distant past, I’ve included many from the modern era as a reminder that mystics walk among us in all times and places. My only criteria for inclusion was that they could not still be living. While there are mystics among us today, their lives are still unfolding, and they can, and should, speak for themselves. You’ll also notice that I mostly refer to the mystics by their first names. Since I consider each of them a soul friend, this feels appropriate and is not intended as disrespect.

Each day’s entry includes a reflection for meditation, prayer, journaling, walking, listening to music or however else you may practice. These reflections are intended to unclog your spiritual pipes. To get the most out of these reflections, you must do some kind of practice. Regular practice is the workout of mystical life. You can’t flex your mystical muscles if you don’t pump contemplative weights. The more you practice, the more it becomes habitual, and the less you think about it. The less you think, the more you can just be, and awaken to God’s presence in your life.

Surrender is the hallmark of mystical life.

Finally, lest you get the wrong impression, I have not abandoned modern Christmas with its fantasy and nostalgia. Nor should you, if fantasy and nostalgia are part of what bring you joy. And while I admire those traditionalists who hold off decorating and singing carols until Christmas Eve—and maybe one day I’ll get there—I’m not one of them. As soon as Thanksgiving is over, my family lets the Christmas horse out of the gate. Those first few weeks of December you’ll find me playing all my favorite songs, baking my favorite treats, and watching the classic movies.

The difference now is that I set aside some time each day to practice Advent. Through practice, I’ve been getting better at locating hope, love, joy and peace in my soul. Then, with purpose and intention, I can share those Advent values with those around me, and carry them right on through to Christmas and beyond. As a result, my holidays are much more precious and resilient.

I hope to never witness another event like September 11, 2001. But in the years since, I’ve had others losses, and I will suffer more this year, and in all years to come. I’ve lost dear friends and family. I’ve failed at relationships. I’ve fallen short of my best intentions. Thanks in great part to Advent I’ve been able to integrate those losses into my life and find meaning in pain and imperfection, and to carry all of it with me through the holiday season. No longer do I depend on holding back the darkness or sustaining some unrealistic fantasy about myself, others, or what Advent and Christmas should or must be. I take it as it is, all of it. Now my holidays are rooted not in trying to pull off a storybook Christmas, but in the contemplation of a God who revealed God’s self as the True, the Good and the Beautiful in the form a vulnerable human being come into a messy world…and by embracing the joy and responsibility I have of giving birth to Christ in my own heart.

My wish is that your season be filled with gratitude and wonder; that you take time each day to honor what was, hold what is, and look to the horizon for what is to come; that you grow ever closer to knowing hope beyond hope, love without end, joy unspeakable and peace that surpasses all understanding.

And now, take a deep breath. As you slowly exhale, whisper the Advent prayer that echoes down through the ages: Come, Lord Jesus.

May it be so.

Gregory Durham, Advent 2022

This is beautiful, inspirational, and fantastic. Thank you, Greg, for creating this. I am excited to learn more and to develop a practice. Reading this intro brought tears to my eyes and this is JUST what I need!

So proud of you work! Looking forward to enjoying this during the next 28 days!