Hope is a crushed stalk between clenched fingers. Hope is a song in a weary throat.

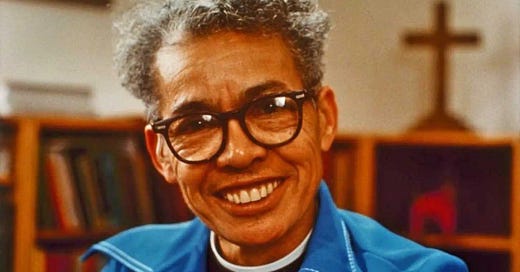

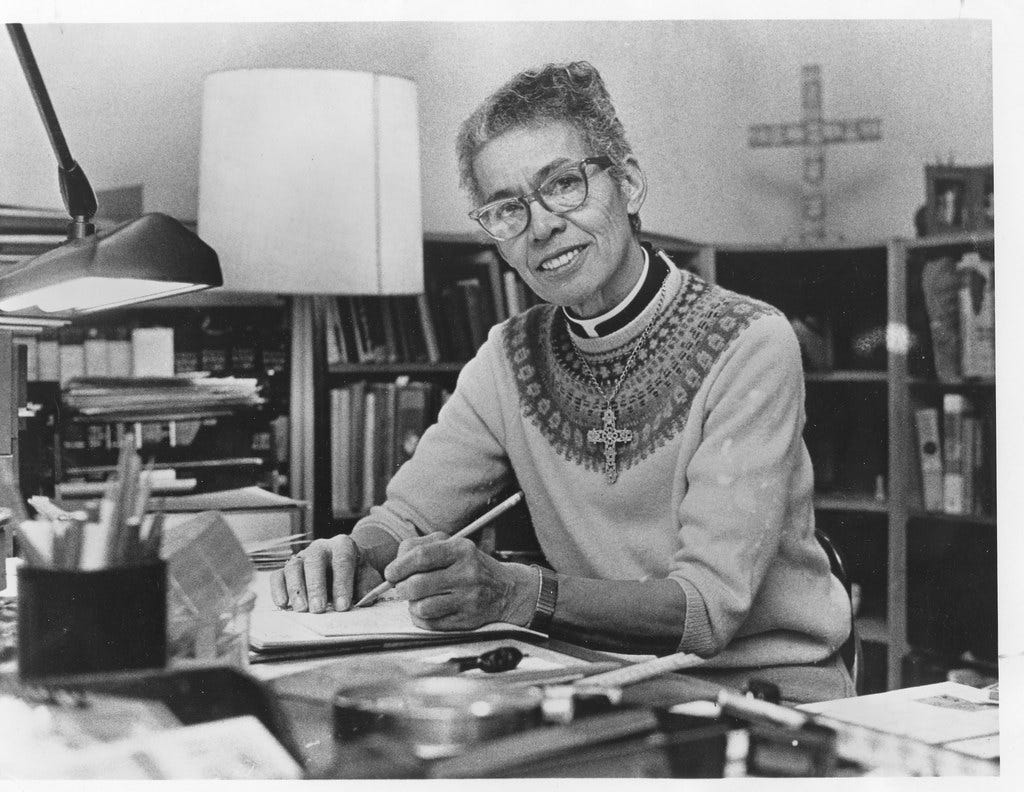

Advent Day 7: PAULI MURRAY (1910-1985)

Of all the mystics, saints and prophets featured in this book, Pauli Murray has had, arguably, the most far-reaching impact on our modern lives. Lawyer, writer, activist, poet, professor, priest—Pauli wore all these hats and more in her pioneering life. And yet, due to a variety of factors, including race and sex discrimination, as well as Pauli’s own unique path, she is, perhaps, the least known to the general public—someone so ahead of her time that time almost forgot her.*

Pauli Murray was born in 1910 and raised in North Carolina. Like so many Americans, she was of mixed ancestry: slave and slave owner, Irish, Cherokee. Feeling the presence and pull of all these ancestors in her blood, she often referred to herself as biologically and psychologically integrated. But no matter how integrated Pauli felt in her soul, both Jim Crow and Jane Crow—a term Pauli coined to describe policies of sex discrimination—insisted on segregation. These laws dictated where and how she could live, and what opportunities she was afforded (and denied).

In Pauli, however, Jim and Jane Crow faced a formidable foe.

Pauli always felt she was meant for big things. But living her destiny meant escaping the segregated South. In 1926, she moved to New York City and attended Hunter College, one of four Black students in a class of two hundred forty-seven. By the time she graduated, however, the world was mired in the Great Depression. Jobs were few, especially for a skinny Black girl who people often confused for a boy.

During the Depression, Pauli fell in love for the first time, with Peg Holmes, a young White woman from an affluent family. Together, they scratched out a meager existence on odd jobs, camping in woods and on beaches. Like so many others, they found themselves drawn to the social movements sweeping America. At rallies for workers’ rights, Pauli began to think about freedom and dignity, not just as they concerned particular movements, but in all aspects of her life—as a Black person in a segregated society, as a woman shut out from many jobs and institutions, and as a person whose sexual orientation lay outside the mainstream.

As the thirties wound down and economic conditions slowly improved, Pauli felt called to make a difference in the world. The best avenue for that, she believed, was the law where she would be able to combine her prodigious energy with her sweeping mind and writing talent.

In 1938, she applied to the University of North Carolina but was denied due to her race. Pauli didn’t take the rejection lying down.

Incident after incident piling up meant that sooner or later I would either go berserk or I would find a way to protest.

Pauli developed a strategy she would employ again and again throughout life, combining literary talent and courage to try and right wrongs. She called this strategy confrontation by typewriter.

In the UNC case, she went on a public relations blitz, planting stories in the press and writing letters to everyone from the President of the university to the President of the United States. When she got nowhere with the latter, she wrote First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Though she was ultimately unsuccessful at entering UNC, she and the First Lady became so close that Pauli came to consider Eleanor a surrogate mother.

Two years after the UNC campaign, Pauli landed in the news again for refusing to move to the back of the bus in Petersburg, Virginia. Three years after that, now studying at Howard University Law, she was, once more, shaking things up by leading lunch-counter sit-ins at a popular D.C. restaurant. Note that these actions occurred, respectively, fifteen years before Rosa Parks was arrested, and seventeen years before student activists desegregated Woolworth lunch counters. As with most mystics and saints, Pauli lived out on the frontiers of life. And like one of her favorite prophets, John the Baptist, she was blunt, clear-eyed and no-nonsense.

After finishing first in her class, Pauli was entitled to continue studies at Harvard Law which, every year, granted automatic admission to the top Howard graduate. However, Pauli was denied entry because Harvard did not yet admit women. Instead, Pauli went to the University of California in Berkeley after which she began a ground-breaking career.

Pauli’s list of accomplishments is staggering. She was the first Black assistant attorney general in California history. Thurgood Marshall—without crediting Pauli, at first—used the arguments she laid out in her book States’ Laws On Race And Color to build his challenge against separate-but-equal policies in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case. President Kennedy appointed her to his Commission on the Status of Women. She co-founded the National Organization of Women with Betty Friedan. And when Ruth Bader Ginsburg incorporated Pauli’s arguments into her brief while litigating Reed v. Reed—the groundbreaking case that extended the 14th amendment’s equal protection clause to women—the future Supreme Court justice credited Pauli as her co-author.

By her early sixties, Pauli had achieved tenure as a professor of law and politics at Brandeis University. As Pauli put it, she had lived to see her lost causes found. But she wasn’t yet done making waves. Soon, her restless energy and desire to push ever deeper led her to a move that shocked friends and family: she entered seminary.

For Pauli, religion wasn’t a left turn but a logical move deeper into her life’s work. Fighting racism and sexism had never been about changing laws as much as changing hearts. It had been a spiritual quest to move America closer to the principles espoused not only by its Constitution but the gospel of Jesus which most Americans professed to believe. The way Pauli saw it, if America was to continue moving forward, it needed healing and reconciliation. It needed God.

In 1977, she became the first Black woman ordained as an Episcopal priest.

Whatever future ministry I might have as a priest, it was given to me to be a symbol of healing. All the strands of my life had come together. Descendant of slave and of slave owner, I had already been called poet, lawyer, teacher, and friend. Now I was empowered to minister the sacrament of One in whom there is no north or south, no black or white, no male or female—only the spirit of love and reconciliation drawing us all toward the goal of human wholeness.

Ultimately, Pauli held a deep hope, an Advent hope, that what goodness we can’t yet see or imagine is not only possible, but is already on its way.

*A postscript on Pauli Murray: Throughout her life, Pauli struggled with how to define her sexual and gender identity. Though her most significant romantic relationships were with women, she never publicly declared herself as gay because doing so would have disqualified her from nearly every job she ever held (for most of Pauli’s life being gay was illegal; Illinois was the first state to decriminalize being gay, and then only in 1962 when Pauli was in her fifties). And though she felt stereotypically male in many ways—and in the 1940s tried, unsuccessfully, to get testosterone treatments—she never could have defined herself as transgender because the word did not yet exist. Nor was there a transgender movement that would have allowed Pauli to make sense of, and explore, her experience. Some have concluded that, were she alive today, Pauli would identify as a transgender man. While this may very well be true, we will never know for certain. As Pauli is not here to speak to this, and since, in her lifetime, she always presented and referred to herself as a woman, I am following the lead of most scholars—as well as Pauli herself—by using female pronouns.

Practice

Pauli Murray was a supremely hopeful person who spent her life out on the leading edge of social movements. In true Advent fashion, she believed that a new day was always dawning. This sustained hopefulness took courage, resilience, and practice. And it would not have been possible without her deep belief in reconciliation.

Where in your life are you seeking reconciliation? What relationships have you let go that you would like to revive?

Pick a relationship, whether friendship, familial or community, and commit to breathing new life into it. Write down one action you will take to make this happen (e.g. go to coffee with an old friend, return to church, call a sibling you haven’t talked to in a long time, etc.). Post this plan-of-action somewhere you will see it until the action has been implemented.

Bonus

If you have Amazon Prime, I highly recommend watching the award-winning documentary My Name Is Pauli Murray.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

Dec. 11, 11:15 am: LITC’s original musical, Make Room In Your Heart.

Dec. 21, 7:30 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the longest night of the year.

Dec. 23, 7:30 pm: Our annual Christmas Eve-Eve service.

Dec. 25, 11:15 am: Celebrate Christmas morning with your church family.

Jan 1, 11:15 am: A quiet, contemplative service to welcome 2023.

Catch Up On Recent Posts

Read the Introduction to The Heart Moves Toward Light: Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets.

Previous posts in this Advent series can be found in our Archive.