The beginning of love is to let those we love be perfectly themselves, and not to twist them to fit our own image. Otherwise we love only the reflection of ourselves we find in them.

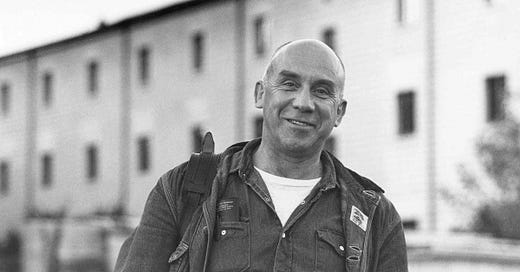

Advent Day 9: Thomas Merton (1915-1968)

In 1949, the hottest book among America’s youth was not a murder mystery or a celebrity biography, but the spiritual memoir of a Trappist monk who’d traded a promising literary career for a life of manual labor and contemplative silence.

The cultural arbiters of taste were baffled. How did a monk get to be all the rage with the kids? The NYTimes went so far as barring the book from its bestseller list, dismissing it as merely religious. But even without the blessing of the cognoscenti (who eventually came around), The Seven Storey Mountain sold millions and sparked interest in the monastic life among the youth of America.

It shouldn’t have been surprising in 1949 that young people were drawn to Thomas Merton’s quest for meaning. This was a generation forged in the fires of war and unrest. Born during the horrors of World War I, they spent their childhoods in the heady boomtimes of the 1920s, came of age in the bust of the Great Depression, and entered adulthood at the dawn of World War II with its industrial-strength death and destruction, which many witnessed first-hand as soldiers. For those haunted by images of concentration camps and mushroom clouds, America’s new post-war mass religion—conspicuous consumption—offered cold comfort.

Thomas Merton’s life embodied the upheavals of his generation. Born in 1915 in France, his family fled for New York (his mother was American) during World War I. After his mother died of cancer, Thomas’s father sent him to boarding school in France then, later, summoned him to England. There, Owen Merton died, also from cancer. Orphaned, Thomas returned to New York where he enrolled at Columbia University.

Even in the depths of the Depression, New York offered plenty of pleasure and vice, and Merton was an eager hedonist. He pulled all-nighters at jazz clubs with frantic drinking, smoking and having a good time. He was sexually adventurous. He dabbled in Communism. He made lots of friends, mostly artists and writers. He had his own ambitions to be a famous writer, and his teachers believed he had the talent to do just that.

But for all Thomas’s popularity and promise, he felt spiritually empty. His pleasure-seeking, promiscuity and professional ambitions, he came to believe, were desperate attempts to prop up an enormous, selfish and greedy ego—what, later, he would term his false self.

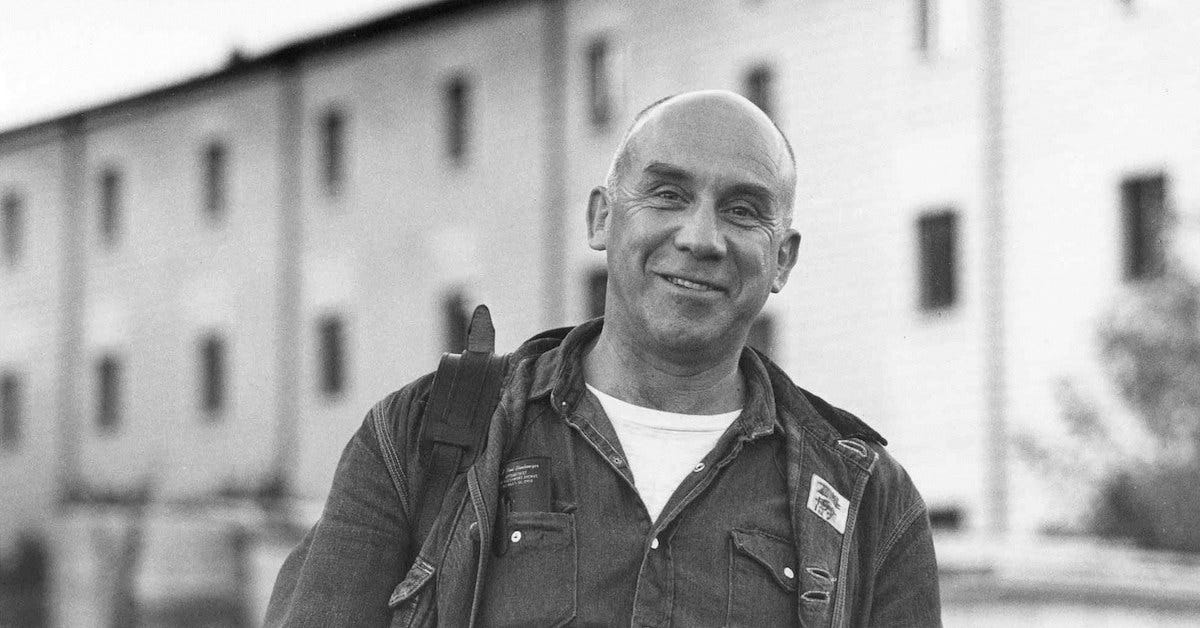

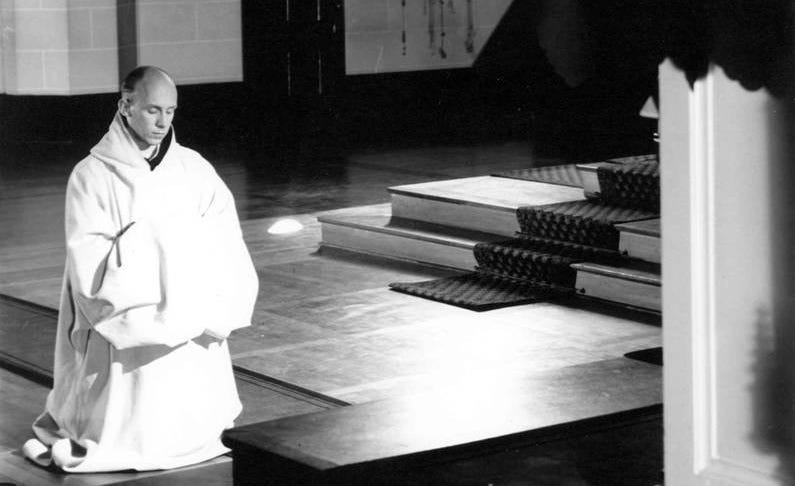

In search of his true self, he entered the Catholic church. Excited by the spiritual discipline he found there, he decided to pursue a monastic vocation with the Franciscans. When the Franciscans rejected him after he admitted having fathered a child, he turned to the Trappists. On December 10, 1941—three days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor—he entered the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky which he would call home for the rest of his life.

Though Thomas thought he was forsaking his literary ambitions by becoming a monk, his abbot at Gethsemani insisted he continue writing as his gift to the world. The first fruits of this labor was his spiritual memoir, The Seven Storey Mountain. After the surprise success of the book, Merton’s output was prolific, turning him into that most paradoxical of creatures: a world-famous hermit.

With his fans regularly showing up at Gethsemani, busyness overtook Thomas’s life. Overwhelmed by the attention, he often sought retreat in the monastery’s book vault. In the silence of the vault he communed with God and refreshed his spirit, discovering the unity with the timeless Divine that would infuse the rest of his life and work.

We are already one. But we imagine that we are not. And what we have to recover is our original unity. What we have to be is what we are.

As Thomas uncovered his true self he began seeing God everywhere—in animals, art, nature and his work. But as with most of us, loving people was harder for Thomas than loving trees or books, and it came last, occurring in the mid-1950s, on the corner of Fourth and Walnut on a day he went to Louisville to see the dentist.

I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all those people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was like waking from a dream of separateness…if only everybody could realize this! But it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun. . . .

After this awakening, Thomas began to merge his contemplation with a commitment to action. In his writing, he took on the issues of the day—racism, nuclear weapons, poverty and the growing conflict in Vietnam. He urged fellow Christians to lend their hands in fixing these problems. The cloistered monk came to realize that our salvation could only happen by and through engaging in loving, contemplative action in community.

Living with other people and learning to lose ourselves in the understanding of their weakness and deficiencies can help us to become true contemplatives. For there is no better means of getting rid of the rigidity and harshness and coarseness of our ingrained egoism, which is the one insuperable obstacle to the infused light and action of the Spirit of God.

Community was key. Merton believed you could not reach the fullness of spiritual life on your own.

Do you think the way to sanctity is to lock yourself up with your prayers and your books and the meditations that please and interest your mind, to protect yourself, with many walls, against people you consider stupid?

Not possible, Merton said. We have to tune into the divinity of every person.

…if Christ became Man, it is because He wanted to be any man and every man. If we believe in the Incarnation of the Son of God, there should be no one on earth in whom we are not prepared to see, in mystery, the presence of Christ.

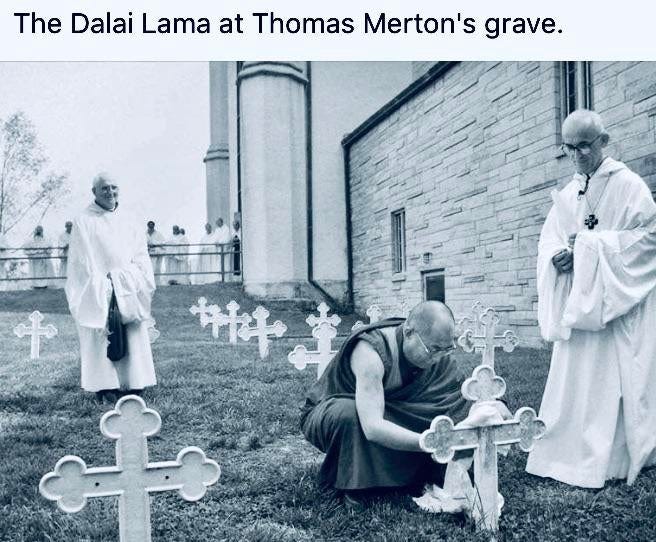

Throughout the 1960s Thomas’s fame grew. He was sought out by the spiritual luminaries of the day: Abraham Joshua Heshel, Thich Nhat Hanh, Martin Luther King, the Dalai Lama and other leaders on the forefront of social action and contemplative religion. With the demands on his time, he struggled to balance interest in him and his desire to lend his voice toward positive social change (action) with his need for solitude (contemplation). Due to his stance against the Vietnam War he began receiving death threats and considered moving to a remote monastery in Alaska. So in 1968, when an invitation to a monastic retreat in Thailand arrived, he accepted it as welcome diversion.

In Bangkok the morning of December 10 Thomas gave a talk. After, he returned to his room where he turned on a fan and was electrocuted by an exposed wire. In a precious irony, his body was returned to the United States alongside the bodies of soldiers killed in the war of which he’d become such a critic.

Decades after his death, in a world wracked by instability, pollution and polarization, where social media and other forces conspire to keep us in our echo chambers, Merton’s unitive message, revealed on a busy Kentucky street corner—God is all and in all—is more needed than ever.

Oh, God, we are one with You. You have made us one with You. You have taught us that if we are open to one another, You dwell in us. Help us to preserve this openness and to fight for it with all our hearts. Help us to realize that there can be no understanding where there is mutual rejection…Fill us then with love, and let us be bound together with love as we go our diverse ways, united in this one spirit which makes You present in the world, and which makes You witness to the ultimate reality that is love. Love has overcome. Love is victorious. Amen.

Practice

Thomas Merton said:

Love is our true destiny. We do not find the meaning of life by ourselves, alone—we find it with one another.

As iPhones, Netflix and Facebook have colonized our lives, so have isolation, stress and anxiety. Sociologists warn of an epidemic of loneliness sweeping the land. Time on TikTok has to come from somewhere. According to the experts, it mostly comes from the things that give our lives meaning and purpose: time spent in community. We increasingly skip church, dinner with the family, sleep, walks with the dog, and coffee with friends. And COVID has only made the problem worse.

Unfortunately, we’re fighting our brains on this one. According to Yale professor Laurie Santos, we have strong intuitions about what will make us happy—earning more money, climbing the corporate ladder, eating a pint of Haagen-Dazs, skipping church, binge-watching Netflix, avoiding people who might irritate us or with whom we disagree on this or that matter. But our intuitions are usually wrong!

So, what’s the cure?

Spending time with actual people.

According to Santos, we can override our hard-wiring by forcing ourselves to get out and be in community. Through action we re-establish and strengthen the brain-body-soul connection. Then we remember (or learn, if we never knew) that things like hanging out with friends, doing 5 million squats at CrossFit, or showing up at church deepens our days. Eventually we rewire ourselves and start choosing flesh-and-blood friends over Facebook.

Of course, being in community is challenging because people are challenging. Even a spiritual genius like Thomas Merton struggled with the temptation to self-isolate so he wouldn’t have to deal with his fellow monks. But he eventually came to realize that you can’t love what you hold at a distance. You only truly love what you’re willing to hold close by love and curiosity and grace, no matter how difficult that can be sometimes.

Today, pick a community in which you have found, or think you might find, meaning and purpose—family, friends, church, gym, social group. Write or meditate on what holds you back from joining a new community, or rejoining one you used to be a part of. Sometimes we have good reasons for moving on or not joining in. Other times we don’t (though our egos—our false selves—convince us we do; sorting that out can be a major challenge in and of itself). Do a fierce Advent inventory of your feelings and make some commitments to strengthen your community ties, however that looks for you.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

Dec. 11, 11:15 am: LITC’s original musical, Make Room In Your Heart.

Dec. 21, 7:30 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the longest night of the year.

Dec. 23, 7:00 pm: Our annual Christmas Eve-Eve service.

Dec. 25, 11:15 am: Celebrate Christmas morning with your church family.

Jan 1, 11:15 am: A quiet, contemplative service to welcome 2023.

Catch Up On Recent Posts

Read the Introduction to The Heart Moves Toward Light: Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets.

Recent posts can be found in our Archive.

I have read everyone of your pieces so far, you have an excellent talent for storytelling and I am enjoying this. Just wanted to let you know there’s somebody out there are you are connecting with what you’re doing. Many blessings for your day.

Greg, check out “Even in the depths of Depression, New York offered plenty pleasure and vice, and Merton was an eager hedonist.” Missing word?