Christmas is waiting to be born: in you, in me, in all mankind.

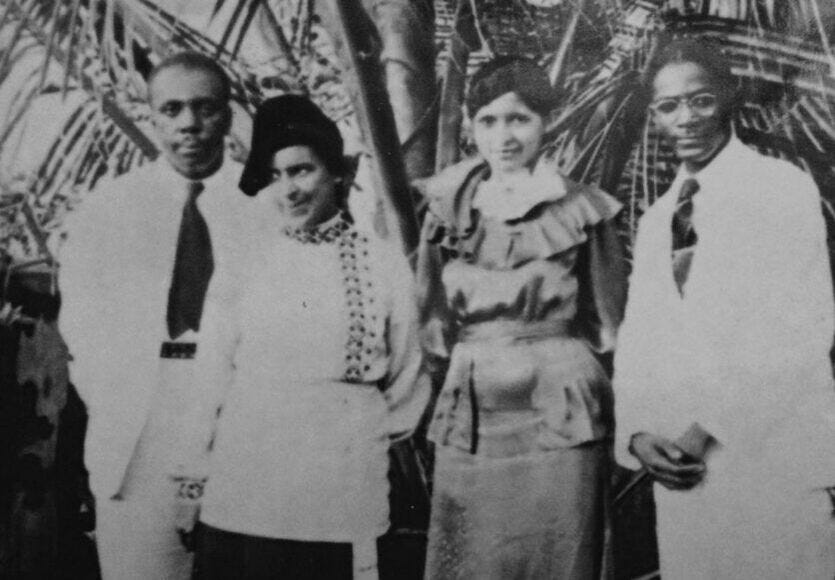

Advent Day 3: Howard Thurman (1899-1981)

Nearly all new life begins in dark. Seeds lie dormant in the earth before blossoming into wildflowers. A caterpillar sprouts wings in the solitude of a cocoon. Each of us reading this floated for months in a pitch-black womb before entering the bright world. Likewise, most of the marquee moments in the Advent and Christmas story occurred at night: Gabriel’s visit to Mary, Joseph’s dream, Jesus’s birth, the arrival of the magi, the flight to Egypt.

Howard Thurman, great Christian mystic and spiritual mentor to Martin Luther King, Jr., saw the dark—literal and metaphorical—as a friend of the soul, often referring to it as luminous. In his autobiography With Head And Heart, Thurman writes about the nights of his Florida childhood:

Nightfall was a presence. The nights in Florida…as I grew up…were not dark; they were black. When there was no moon, the stars hung like lanterns, so close I felt that one could reach up and pluck them from the heavens. The night had its own language…I could hear the night think and feel the night feel. This comforted me. I felt embraced, enveloped, held secure.

On these dark childhood nights, Howard Thurman found a light that radiated from within. That light became his inner authority and his Advent hope—hope not only that something new was at work in the world, but that he could be an instrument of the newness.

Born in 1899 in Daytona Beach, Howard’s childhood days were lived behind the high walls of segregation. But in the dark, those walls crumbled, and his imagination roamed beyond the gaze of Jim Crow, down the paths of possibility. His expansive sense of possibility eventually led him far from home.

At age thirteen—and with the encouragement of his grandmother, a former slave—he left Daytona for Florida Baptist Academy, one of only three private schools open to Black children in Florida at the time. After graduation he attended Morehouse College in Atlanta then the Rochester Theological Seminary in New York, graduating valedictorian from both. Eventually he served as dean at both Howard University and Boston University, and co-founded San Francisco’s Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples, the first intentional multi-racial church in America.

Howard had been mystically-inclined since childhood. But it was in 1929, while studying under famed Quaker Rufus Jones, that he took up formal meditation. Jones taught Howard that it was in the silent dark where you were best able to awaken to God. Once awakened, you had not only the ability but the responsibility to change the world for the better. These teachings combined with his own mystical experiences led Howard to begin developing a philosophy that merged activism, faith, spiritual discernment and pacifism.

In 1935, Howard’s interest in combining action with contemplation got a shot in the arm when he traveled to India to meet Gandhi. There, the famed Indian moral leader expressed regret that, up to that point, the principle of nonviolent resistance had not caught worldwide interest. He challenged Howard to dig into the gospels and the life of Jesus to develop a Christian philosophy of nonviolence. If he could do this, Gandhi said, then perhaps it would be through the Black struggle in America that the world would finally come to know peaceful resistance.

Understanding that any peaceful movement hoping to destroy segregation would require deep inner discipline and an ability to transcend fear, suspicion and hatred, Howard spent the next fifteen years studying Jesus’s resistance to the Romans and the ruling elites who’d been corrupted by Rome. The challenge was figuring out how to combine political confrontation and contemplation as a spiritual discipline. This culminated in his groundbreaking book Jesus and the Disinherited which laid the moral framework for the modern American civil rights movement. If a civil rights movement was to succeed, Howard ultimately concluded, it would have to be grounded in love.

The religion of Jesus makes the love-ethic central. Every man is potentially every other man’s neighbor. Neighborliness is nonspatial; it is qualitative. A man must love his neighbor directly, clearly, permitting no barriers between.

This was no easy matter for Jesus and his followers who faced opposition from all sides.

A twofold demand was made upon him at all times: to love those of the household of Israel who became his enemies because they regarded him as a careless perverter of the truths of God; to love those beyond the household of Israel—the Samaritan, and even the Roman.

In the 1950s, in a meeting that now seems divinely ordered, Howard began mentoring a Boston University student named Martin Luther King. Howard taught his philosophy to King who, within a couple years, was leading the Montgomery bus boycott. It was reported that King carried Jesus and the Disinherited in his pocket wherever he went.

Though Howard did not join in direct action during the Civil Rights movement, his stature as one of America’s great spiritual leaders took off. As demands for his time and attention grew, he increasingly sought out solitude for prayer and meditation. Eyes closed, heart and mind quieted, in contemplation’s dark he found union with the Light.

Light that could only be seen by going into the darkness was the recurring motif of Howard’s life. In the prologue for Luminous Darkness, his 1965 book on segregation, he related a story about one of his students who’d spent time deep-sea diving. The student told Thurman about the descent through layers of aquatic life, into a zone where no light penetrates. Fear and panic grips the diver. But, as he goes lower, the diver’s eyes adjust to the dark and he acquires peculiar vision that allows him to see a luminous quality.

The parallels between the diver’s descent, liberation movements and the mystical journey toward God were obvious to Howard. In all cases, darkness—if one can stick it out—eventually becomes infused by a paradoxical light.

The dark was Howard’s ticket to the Light. As a child in the dark he found comfort and the strength to survive and resist segregation. As an adult mystic in the dark he found God. The deep darkness of prayer and meditation allowed him a space to meet God and to meet himself, stripped of all his identities. Spiritually naked, he felt himself washed in the Light, and returned to his true self where all distinctions fell away.

It is my belief that in the Presence of God there is neither male nor female, white nor black, Gentile nor Jew, Protestant nor Catholic, Hindu, Buddhist, nor Muslim, but a human spirit stripped to the literal substance of itself before God.

In humble prayer and contemplation, Howard heard what he poetically called the sound of the genuine. This was “music” available to anyone willing to practice the spiritual disciplines of opening their heart to the love of God in themselves and others. In a commencement address delivered at Spelman College in 1980, less than a year before his death, he sketched a vision of radical solidarity built on Jesus’s love-ethic which, he believed, was the only thing that might save the world.

Now if I hear the sound of the genuine in me, and if you hear the sound of the genuine in you, it is possible for me to go down in [my spirit] and come up in [your spirit]. So that when I look at myself through your eyes having made that pilgrimage, I see in me what you see in me. [Then] the wall that separates and divides will disappear, and we will become one because the sound of the genuine makes the same music.

Practice

Howard Thurman’s favorite scripture was Psalm 139. Read it then find reflection questions below.

Verses 11-12 read: You’d find me in a minute—you’re already there waiting! Then I said to myself, “Oh, he even sees me in the dark! At night I’m immersed in the light!” It’s a fact: darkness isn’t dark to you; night and day, darkness and light, they’re all the same to you.

Howard Thurman loved the darkness—both the literal darkness of night and the figurative darkness of meditation and quiet spaces. Darkness, he believed, led to true knowing, of God and oneself.

Find the quietest spot you can. Set a timer for a minimum of five minutes. Then close your eyes and try to be completely present to the moment: your breathing, the temperature, sounds. The trick is to be present without your thoughts running away toward the past or future. To help rein in your thoughts, pick one word, like God or love or peace. When you catch yourself thinking, silently or quietly repeat this word then resettle in silence. If you have to repeat it over and over like a mantra, that’s fine.

This practice is harder than you think, but it’s the start of sustained contemplation. If you do this every day during Advent, even if only five minutes, you will see progress in your ability to sustain presence.

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

Dec. 11, 11:15 am: LITC’s original musical, Make Room In Your Heart.

Dec. 21, 7:30 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the longest night of the year.

Dec. 23, 7:30 pm: Our annual Christmas Eve-Eve service.

Dec. 25, 11:15 am: Celebrate Christmas morning with your church family.

Jan 1, 11:15 am: A quiet, contemplative service to welcome 2023.

Catch Up On Recent Posts

Read the Introduction to The Heart Moves Toward Light: Advent With The Mystics, Saints and Prophets.

Previous posts in this Advent series can be found in our Archive.

Man I need to catch up! How are these getting by me? So good, friend. Love Thurman and so love you pulling out the theme of darkness. "Prophet of the luminous dark" might be my new favorite phrase. I'm jumping around and not reading these in order, but I love how when we read about each of these spiritual teachers one after the other, we can see so clearly the threads that connect them.

I’d definitely read that one next! 😉