The spiritual life does not remove us from the world but leads us deeper into it.

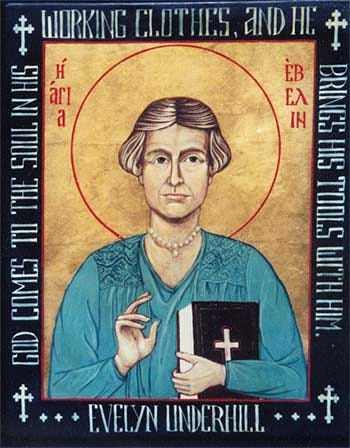

Advent Day 12: Evelyn Underhill (1875-1941) and C.S. Lewis (1898-1963)

Their friendship began as a fan letter written in October 1938 by Evelyn Underhill, England’s most towering Christian figure during the first half of the 20th century:

May I thank you for the very great pleasure which your remarkable book Out of the Silent Planet has given me? It is so seldom that one comes across a writer of sufficient imaginative power to give one a new slant on reality [but] this is just what you seem to me to have achieved. And what is more, you have not done it in a solemn, oppressive way but with a delightful combination of beauty, humor and deep seriousness.

The recipient was C.S. “Jack” Lewis. Though in the second half of the century, Jack would succeed Underhill as England’s most towering Christian, in 1938 he was still an unknown novelist. So, supportive words from one of his great spiritual role models came as a welcome surprise.

Jack wasted no time before writing back.

Your letter is one of the most surprising and, in a way, alarming honors I have ever had. I have not been for very long a believer and have hitherto regarded the great mystical writers as a man in the foothills regards the glaciers and precipices: to find myself noticed from regions which I scarcely feel qualified to notice is really quite overwhelming.

Jack was thrilled to bask in the glow of Evelyn’s attention. Especially satisfying to him was that, unlike the book’s reviewers, she had both picked up on and found meaning in the theological threads woven throughout his novel. Warmed by her encouragement, he decided to develop another story with deep spiritual themes, about a group of siblings who walk through a wardrobe into a magical realm.

Nothing in Evelyn Underhill’s young life predicted her trailblazing future. Born in 1875, she was raised in a conventional Victorian-era upper middle class home. Her mother was a homemaker, father a lawyer. Evelyn attended a respectable girls’ school. Their home was comfortably outfitted with late-19th century modern conveniences like indoor lighting and flush toilets. They took pleasant seaside vacations.

Scratch that surface, however, and you find a highly unusual fact of Underhill life: young Evelyn was an avid church-goer while her agnostic parents shunned Sunday services. She was drawn there, she said later, by a stirring in her young soul, “…abrupt experiences of peaceful reality—like the 'still desert' of the mystic.”

Evelyn’s early adulthood, in my many ways, mirrored her childhood. She married a lawyer like her father who did not share her spiritual leanings. Like her mother, she set up a comfortable home and dabbled in charity work appropriate for a middle class Victorian woman. Yet signs of her future maverick life were emerging. Unlike most women of her time, she pursued higher education, at Kings College of London. She also launched a writing career, publishing first poetry and then novels.

But it was in 1898, during a solo trip in Italy, that the Evelyn Underhill the world would come to know began to emerge. There, in a country barely touched by the modern world and still alive with mystery, Evelyn felt her soul awaken. In village churches adorned in frescoes, in widows praying the rosary in town squares, in public festivals devoted to saints (many of them women completely unknown to her own Anglican tradition), in the architecture, blue sky and wildflowers, she felt the presence of a wild, transcendent God who was in everyone and everything, everywhere, all at once. Her life would never be the same.

Upon returning to England, Evelyn immersed herself in the Christian mystics who, by the end of the 19th century in England, had been mostly forgotten outside of monasteries. She traced the lineage backward from Brother Lawrence and Meister Eckhart to Teresa of Ávila and Julian of Norwich, all the way down to the Desert Mothers and Fathers.

In them she discovered not saintly saints but everyday men and women who led lives rooted in contemplation, love, service and self-examination, and whose free-range spirituality led them to “…live and look and speak the disconcerting language of first-hand experience, not the neat dialectic of the schools.” This path always led them to a wild and mysterious God who could be felt and experienced but not contained nor explained.

So long as the object of the mystic’s contemplation is amenable to thought, and is something which they can “know”, they may be quite sure that it is not the Absolute, but only a partial image or symbol of the Absolute. To find that final Reality, one must enter into the cloud of unknowing.

Evelyn now made it her life’s mission to revive the mystics and their teachings, and to show people that the mystical path was wide open to all.

We are all the kindred of the mystics; we are all potential contemplatives. The Eternal Wisdom is knocking at the door of your heart.

In her first book on the topic, entitled Mysticism, Evelyn urged readers to reclaim their religion, turning it back from the heady assent to doctrine it had become to the heart-centered experience it had once been. In other words, a return to the love that is the core of the Christian journey.

Mysticism is…a love affair with the Absolute….It is love, not logic, which is the strongest force in the universe. Love is the greatest of all acts, the essential energy of the spiritual life. In love, the soul gives itself wholly to God and finds its true life…

Mysticism was an instant bestseller. It, and the three dozen books that followed in the coming decades, made Evelyn a household name, and an in-demand public authority on spirituality. In time, she became the first woman to lecture at Oxford University, and the first woman and lay person to lead spiritual retreats for clergy. Her articles appeared in nearly all of the era’s leading publications. With the spread of radio in the 1920s, she became a popular guest on the new medium.

Through it all, Evelyn preached an eminently practical mysticism. This was not a path reserved for clergy, religious scholars or the particularly pious. In fact, these were often the ones who had the most difficulty moving from head- to heart-centered faith. Rather, mysticism—rooted in everyday life—was for everyone.

Mysticism is the science of love. It invites us to see with our hearts as well as our minds. The first duty of the practical mystic is to cultivate an alert and humble attention to life, as it is the window through which God is glimpsed. God is always coming to you in the Sacrament of the Present Moment. Meet and receive Him there with gratitude in that sacrament.

Beauty and love were all around, if we only had eyes to see and ears to hear.

For lack of attention a thousand forms of loveliness elude us every day.

Evelyn’s way was not a flight from reality, but an immersion in it.

The spiritual life does not remove us from the world but leads us deeper into it.

As such, she generally recommended against conventional feats of piety which, in her view, overcomplicated God. Rather, she recommended a humble balance of action and contemplation: meditate then go serve the poor; say your prayers then help a neighbor in need.

Deliberately seek opportunities for kindness, sympathy, and patience. The spiritual life has to be extended both vertically to God and horizontally to other souls…If in the next life we could feel sure of being met by even one soul who said to us, through you, God found me, I think that would be sufficient for our beatitude.

There is something bittersweet about the timing of Evelyn’s friendship with C.S. “Jack” Lewis. By the mid-1930s, her star was waning just as his was on the rise. Her declining popularity had much to do with her pacifism in the lead-up to World War II. This stance was born out of the horrors of the previous war, only two decades earlier. Evelyn believed—hoped beyond hope—that there was a path to resolving Europe’s conflicts other than a return to wholesale slaughter.

Pacifism, however, has never been a popular stance, in any time or place. Evelyn’s convictions put her at odds not only with the public mood, but also with many family and friends. In the face of such criticism, her friendship with Jack, whose talent and future she believed in, provided a welcome reprieve.

Of their exchanges, the last, only months before her death, is perhaps the most fascinating. In a 2015 article, author Carl McColman points to it as evidence of Evelyn’s long-lasting impact on the young C.S. Lewis. It was a discussion over his book, The Problem Of Pain, in which he showed an attitude toward animals that seemed to implicitly criticize Evelyn’s wild-and-free spirituality. He wrote:

The tame animal is in the deepest sense the only natural animal…the beasts are to be understood only in their relation to man and through man to God.

Evelyn, who’d spent years trying to free a wild God from centuries of domestication, was having none of it:

This [is] an intolerable doctrine…Is the cow which we have turned into a milk machine or the hen we have turned into an egg machine really nearer the mind of God than its wild ancestor? You surely can’t…think that the robin redbreast in a cage doesn’t put heaven in a rage…

She goes on to make a case for the inherent, God-given beauty and value of creatures:

…if we ever get a sideway glimpse of the animal-in-itself, the animal existing for God’s glory and pleasure and lit by His light (and what a lovely experience that is!), we don’t owe it to the Pekinese, the Persian Cat or the canary, but to some wild, free creature…

She closes her critique with a classic Underhill kicker:

I feel your concept of God would be improved by just a touch of wildness.

A few years after this discussion, Jack—whose own spirituality, influenced by Evelyn, was gradually moving beyond the domesticated and into the wild—would publish The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe. In this fable, he introduces a cast of wildly, delightfully, sometimes dangerously free-spirited animals. Most notable among them is the lion Aslan who is described by the character of Mr. Beaver as not safe but, also, good. Of the Christ-like Aslan, Mr. Beaver says, “He’s wild, you know, not like a tame animal.”

As Carl McColman says in his article, “…Evelyn Underhill would have heartily approved.”

Evelyn died on June 15, 1941 at age sixty-five. Her friend Jack lived another twenty-two years. Today they are considered among the most towering figures in modern Western spirituality.

Practice

One of my favorite Evelyn Underhill quotes is:

The spiritual life does not remove us from the world but leads us deeper into it.

Like Brother Lawrence, Therese of Lisieux and most other contemplatives and mystics, Evelyn found God not in ecstatic experiences and devotional escapism but in nature, art, everyday living and acts of service (her prescription for getting out of your head and into your heart was to go serve the poor, which she did for decades in London). In other words, not a remove from the world but a descent into it.

For today’s practice, take an everyday task—doing dishes, washing laundry, cooking a meal, taking a walk, etc. Then, rather than going about it in a rote manner, see if you can connect to what Evelyn called the sacrament of the present moment. Bring your attention to whatever it is you’re doing. How does it feel in your body? What do you feel, touch, taste, see or smell? How does love—for others, yourself and a wild God—infuse this simple act?

Holiday Happenings at Life In The City

All in-person gatherings listed below happen at 205 East Monroe St. in Austin, Texas.

Dec. 8, 11:15 am: LITC’s original musical, Make Room In Your Heart. Dec. 21, 6:000 pm: Blue Christmas, an intimate service for the longest night. Dec. 23, 6:00 pm: Christmas Eve-Eve, and LITC tradition. Dec. 29, 11:15 am: Welcome 2025 with a fun, casual service that includes cookies, coffee, conversation and resolution-setting.

Contemplation In The City

Life In The City’s contemplative community meets regularly to practice sacred traditions like Lectio Divina and Centering Prayer. If you’re in Austin, consider joining us. Upcoming in-person gatherings are Jan. 14, Feb. 4, Mar. 4, Apr. 8, May 6. We meet at 205 East Monroe Street in Austin. Doors open at 6pm for coffee and conversation, service from 7-8pm. You might also find meaning in our monthly newsletter in which we wrestle with how to live a spiritually engaged life in the modern world. Read more here.

Ready For More?

Read the Introduction to the 2022 edition, to find out how my experience of September 11, 2001 became my gateway to Advent.

Find more mystics, saints and prophets in our Archive.

Feedback

Catch a typo? Have suggestions for mystics, saints and prophets for a future year? Leave feedback in the Comments below or email Greg Durham at greg@litcaustin.org.

I pulled so many quotes from today’s post! I am enjoying them all, but this one spoke to me.

This makes me smile to read of their friendship! I had no idea! I love her encouragement and correction of the younger up-and-coming Lewis, especially about the wild animals!